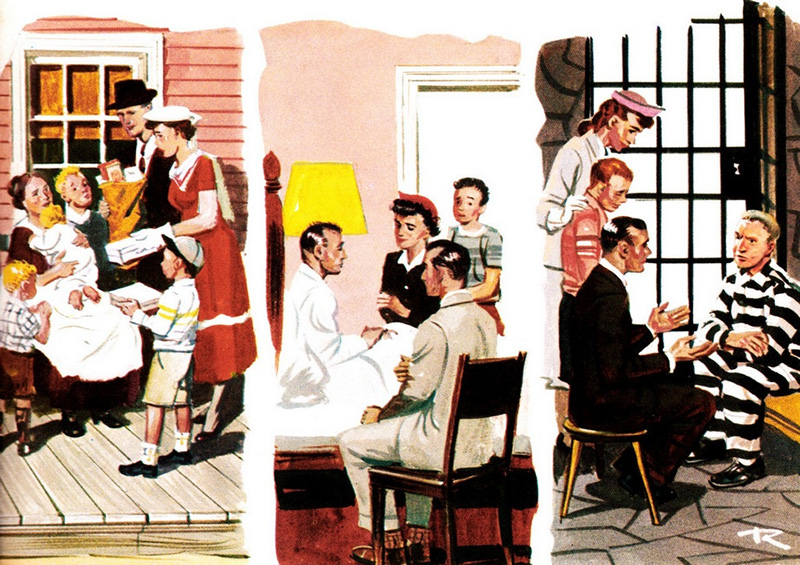

Near the end of Christopher Durang’s satirical one-act play Sister Mary Ignatius Explains It All for You, the title character shoots dead one rebellious former student in self-defense and holds three others at gunpoint before murdering one of them (the gay one). Addressing the audience during a moment of calm between the shootings, Sister Mary Ignatius insists, “Most of my students turned out beautifully, these are the few exceptions.” She then turns to her seven-year-old stage assistant, Thomas. “But we never give up on those who’ve turned out badly, do we?” she asks in obvious bad faith. “What is the story of the Good Shepherd and the Lost Sheep?”

THOMAS: The Good Shepherd was so concerned about his Lost Sheep that He left his flock to go find the Lost Sheep, and then He found it.

SISTER: That’s right. And while he was gone, a great big wolf came and killed his

entire flock. No, just kidding. I’m feeling lightheaded from all this excitement.

Finally, Sister explicates the parable in earnest. “By the story of the Lost Sheep,” she states, “Christ tells us that when a sinner strays, we mustn’t give up on the sinner.”

Sister’s first, unguarded gloss on the story of the Lost Sheep seems to me at least as perceptive as the more orthodox reading. When the Good Shepherd sets out on his search, he does appear alarmingly unconcerned for the safety of the 99 obedient sheep he leaves behind, so single-minded is he about rescuing the problem case. In the same vein, an honest reading of the related Parable of the Prodigal Son yields a fairly subversive set of instructions: Act like an ingrate, squander your premature inheritance on booze, dice, and women, then return to your father’s home once your rebellious streak has run its natural course; there you will be welcomed with open arms and treated not merely as well as but actually more lovingly than your non-rebellious sibling.

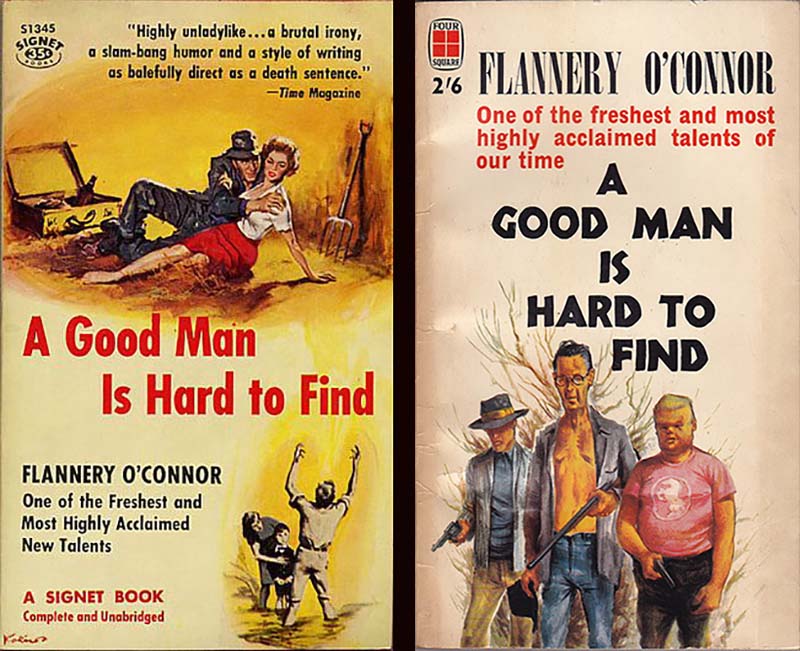

For me these parables serve as reminders of what is intellectually displeasing about the literary oeuvre of Flannery O’Connor, one of America’s most admired authors. Each of her two novels, Wise Blood (1952) and The Violent Bear It Away (1960), address the spiritual fate of a Lost Sheep protagonist (Hazel Motes in the former, Francis Marion Tarwater in the latter). The same is true of much of her short fiction, including O’Connor’s most widely anthologized story, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” (1953), the plot of which has always struck me as amateurish in its design. Because of O’Connor’s acidic humor, critics laud her as an unsentimental writer. But like a corny Hollywood movie in which the rebel son is played by a charismatic star of the first rank, O’Connor’s fiction is marred by sentimental Christianity of the worst kind. I am not alone in recognizing this particular form of sentimentality at work in our religious and popular cultures. A Muslim colleague of mine is fond of observing, “A Christian would be stupid not to sin a lot.” He means that the God of Christianity seems to cherish sinners more than he does the prematurely devout — so why not have some disobedient fun along the way? As a final indignity, notes my colleague, in the Christianized movie version of our lives, those who never misbehave get played by balding C-list character actors.

The most recent addition to the O’Connor canon, A Prayer Journal (2013), reprints a short devotional notebook the young author kept from January 1946 to September 1947 while she was at the University of Iowa completing an MFA in fiction writing. The Prayer Journal’s contents, with the exception of one brief passage, shed little light on the most annoying aspect of the author’s work: her obsession with prodigal figures. “To all appearances, O’Connor had not yet begun reading in the sophisticated theology that would lift her faith beyond the juvenile,” observed Sarah Gordon, commenting about the apprentice writer’s time in Iowa City in a review of the new volume. Leaving aside for now the issue of theological sophistication, one must indeed consult O’Connor’s mature fiction and nonfiction, as well as biographical materials about the author, to assess her ultimate status as a self-described “hillbilly Thomist.” The troubling thematic roots of O’Connor’s fiction actually extend to the Gospels, not just to the writing of her beloved Thomas Aquinas. The problem in her work runs deep, in other words, but the author chose of her own accord to focus in her fiction exclusively on “the action of grace on a character,” as she phrased it in a letter. “It seems to me that all good stories are about conversion, about a character’s changing,” she commented, suggesting that her work was as captive to a literary or structural imperative as to a theological one. Still, it is the theological imperative that impels me to reject her fiction. In a piece titled “In the Devil’s Territory,” O’Connor explained, “In my stories a reader will find that the devil accomplishes a good deal of groundwork that seems to be necessary before grace is effective.” The worse, the better, in other words, if one is ultimately aiming for salvation.

In a work of fiction, according to this line of thought, it is not enough for a character to meet a lifetime of challenges to his or her faith; rather, any such figure, to be useful, must demonstrate a prodigal’s full-blown disloyalty and irresponsibility in preparation for subsequent conversion or re-conversion. Justifying this method of storytelling is the same religious impulse that can convince a soon-to-be-disgraced minister not merely to break his wedding vows but to do so by organizing an orgy with heroin-addicted prostitutes, for there could be no better way to redirect himself toward the path of righteousness than by sinning in what he considers the most egregious manner. Employing this same logic, 12-step programs encourage potential penitents to truly hit bottom before attempting to curb a destructive addiction.

Not surprisingly, the one theological quirk O’Connor had adopted before arriving in Iowa City involved her fascination with the Satanic figure through whose negative example mankind is directed to God. In the single quote-worthy passage in A Prayer Journal, the 21-year-old student demonstrates that she has already been reflecting upon the relationship between the creator and his disloyal angel. “No one can be an atheist who does not know all things,” O’Connor wrote in early January 1947. “Only God is an atheist. The devil is the greatest believer & he has his reasons.” Like a teenaged boy who eventually manages to outgrow his obsession with heavy-metal music, a wise, adult O’Connor might have distanced herself from this nearly Zoroastrian take on the divine and his evil twin. Instead she put the devil to work in the plots of her novels and stories, wherein Satan’s bad influence serves to goad the protagonists toward salvation. When questioned, O’Connor offered a justification for her beliefs based solely on their profundity. “The doctrines are spiritually significant in ways that we cannot fathom,” was how she typically phrased her defense. “Dogma is the guardian of mystery.”

Compelled as she was to dodge legitimate questions about her fiction’s theological foundations, O’Connor probably should have pursued more varied concerns in her work. A religiously committed writer like her might have explored how the sadistic grouch from The Book of Job morphed into the generous and forgiving God of the New Testament. Or she might have questioned whether the birth of an indigent child could indeed alter the jaded behavior of the adult world and thereby redeem it. At the very least, if the working of God’s grace on a Lost Sheep character had to serve as the author’s only theme — over and over — she might have done a more honest job of balancing our sympathies between the delightfully prodigal and the tediously steadfast. “Here was a very, very limited person,” commented a friend of the author’s after reading an early draft of “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” “The grandmother” — not the story’s Lost Sheep character — “is a completely banal, superficial woman.” His observation was sound in that all intelligence, self-reflection, and depth are initially reserved for the story’s criminally insane prodigal.

•

Despite my reservations about O’Connor’s work — or perhaps because of them — I was well-served by reading Flannery: A Life of Flannery O’Connor by Brad Gooch (2009). Significantly, the biographer uses his subject’s lupus diagnosis to divide the book in half: O’Connor’s initial hospitalization ends Part I, and her commencement of treatment, such as it was, begins Part II. Gooch’s excellent account of a writing career passed under a death sentence does little to alter my personal distaste for the Lost Sheep threads woven into O’Connor’s novels and stories. But the timing of O’Connor’s diagnosis, as recounted by Gooch, helps explain the narrative oddities in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.”

O’Connor published the story in 1953, one year after being told the truth about her medical condition. O’Connor’s mother, having not wished to shock her ailing daughter with news that she — Flannery — was afflicted with the same disease that had killed Flannery’s father, concealed the diagnosis for a year and a half. A friend of the novelist — her future literary executor, Sally Fitzgerald — finally spilled the beans. So it was mere months after learning she had developed lupus O’Connor completed the first draft of a story in which an Atlanta family consisting of two parents, three young children (including an infant), and an elderly grandmother sets out on a journey that will cost them their lives.

Most readers will already have at least a passing familiarity with “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” Robert Giroux, O’Connor’s editor at Harcourt Brace, claimed the piece “absolutely put her on the map.” But a synopsis will help make my point. At the beginning of the story, the grandmother suggests the family take a trip to east Tennessee, where she has relations and where the family would be less likely to encounter The Misfit, an escaped prisoner reported to be heading south. Her suggestion is ignored. En route to Florida the family stops at a restaurant where the grandmother again brings up the subject of The Misfit, this time to their waitress. “I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if he didn’t attack this place,” the waitress replies. “I wouldn’t be none surprised to see him.” Of course, neither should we be surprised. The Misfit doesn’t terrorize the restaurant, but he and two sidekicks assault the family on an isolated back road the grandmother has insisted the family take on a detour. Her foolish behavior, moreover, causes a single-car accident that dumps the injured family members on the side of the road. There they are easy pickings for the three armed criminals.

With implausible efficiency, the two sidekicks escort the father and young son to the nearby woods and kill them; they then walk the mother, young daughter, and infant to the same spot and shoot them too. All the while, the grandmother pleads with The Misfit to change his ways, to pray, to become an honest man — all in a vain attempt to save the lives of her family members or at least her own life. Finally, with the old woman facing the wrong end of the gun barrel herself, the utter hopelessness of the situation delivers a moment of clarity: Rather than mourn the grisly fate of her progeny or contemplate her own imminent death, this Christian woman focuses instead — quite seriously this time — on the urgent need of the story’s villain for salvation. Tellingly, The Misfit has just admitted that, if only he had been on the scene to witness the raising of Lazarus from the dead, he could accept without doubts the truth of Christ’s divinity and he wouldn’t be like he is now — that is, he wouldn’t be a sociopath. “Why you’re one of my babies,” the grandmother assures him, concern for her own physical well-being giving way fully to the realization that The Misfit is a candidate for redemption. “You’re one of my own children!” Alas, the truth hits too close to home: When the grandmother reaches out to touch The Misfit’s shoulder, he reflexively shoots her three times through the chest.

So, just as in Wise Blood and The Violent Bear It Away, in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” — amid all the carnage and the suffering of innocents — the fate of a Lost Sheep character preoccupies O’Connor. The suffering of the other 99 vulnerable members of the flock merely provides the reader with laughs. “She would have been a good woman,” The Misfit comments to his sidekicks about the grandmother after killing her, “if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.” The old woman, he means to say, came to her senses and recognized the full extent of God’s mercy under extreme duress. Only at that point did this nominal Christian accept how, in God’s eyes, her family’s suffering mattered little compared to what was truly important: the salvation of her deranged tormentor. The Misfit was doing her a favor, really. After witnessing the execution of her five family members, the grandmother finally acquired wisdom to which only Flannery O’Connor had heretofore been privy: that it is incumbent upon us as Christians to take seriously the most ill-considered parables from the Gospels and build a spiritual life (and a literary career) around them.

O’Connor’s story, while objectionable in terms of theme, also stumbles over matters of craft and technique. Anyone who has taught an introductory course in fiction writing has probably encouraged novice writers to prepare the reader, subtly, for what is to come. But O’Connor disavows subtlety: The grandmother, like a million other newspaper subscribers in Georgia that week, reads about The Misfit’s prison escape and somehow convinces herself that God in his inexplicable wisdom will send the family’s executioner directly to her — which he does! (I remember, the first time I read the story as a college undergraduate, thinking, “What’s next — a winning Powerball number?”). In his biography, Gooch records advice given to O’Connor by Andrew Lytle, one of her instructors at the University of Iowa. Lytle advised O’Connor to “sink the theme” more deeply in her writing and “clobber” the reader less bluntly. But O’Connor stuck to her guns, both at Iowa and throughout her truncated career.

A second problem concerns the speed and thoroughness with which the family is dispatched. Who, might I enquire, would murder an infant without blinking? Even a trained assassin would probably observe a more conventional moral code under these circumstances; asked to splatter a baby’s entrails for money, he would likely decline. An unhinged serial killer might accept the challenge, I suppose, but such people tend to be anti-social types disinclined to act in concert with others. Perhaps those of us not widely experienced in the business of butchery should simply avoid writing scenes of senseless carnage lest we appear unfamiliar with the workings of an unfathomable mind, which inevitably get played for laughs. I don’t mind the laughs. O’Connor’s famous dialogue can be amusing (“It’s no real pleasure in life,” The Misfit instructs). Rather, I object to her shoehorning unconvincing plot details into a story in the service of a rigid theological design, particularly when the theology is unsavory.

Brad Gooch reports that O’Connor ran into trouble in graduate school when she attempted to include in her fiction other subject matter with which she was unfamiliar. “The only day I felt she fell on her face was when she tried to write about a boy-and-girl situation,” noted one fellow workshop member. Paul Engle, who directed the Writers’ Workshop, recalled, “I explained to her that sexual seduction didn’t take place quite the way she had written it — I suspect from a lovely lack of knowledge.” It fell to Andrew Lytle to point out the implausibility of a scene from an early draft of Wise Blood. “She would put a man in bed with a woman,” recounted Lytle, “and I would say, ‘Now, Flannery, it’s not done quite that way,’ and we talked a little bit about it, but she couldn’t face up to it, so she put a hat on his head and made a comic figure of him.” Cue our resident comic figure, The Misfit, who first emerges from his car absurdly shirtless and in tight blue jeans, holding his black hat — and a gun.

A third problem is the jarring shift at the end of a story heretofore told from the limited perspective of the grandmother. That is, the author makes the novice mistake of killing off prematurely the character from whose point of view the story is being told. For contrast consider the final sentence of Shirley Jackson’s masterpiece, “The Lottery”: “‘It isn’t fair, it isn’t right,’ Mrs. Hutchinson screamed, and then they were upon her.” End of Mrs. Hutchinson, and end of story. At the conclusion of “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” The Misfit and his sidekicks stand over the grandmother’s corpse and converse for half a page. Are we to assume the grandmother is holding on for dear life at this point but, rather than registering the pain of three gunshot wounds, is listening calmly to their conversation? Or could it be that her soul, separated from her body, is hovering nearby and taking it all in?

Obviously I’m nitpicking. A gifted storyteller often succeeds by bending the rules. My revulsion at this prodigal-son narrative is no doubt a personal quirk that says more about me than about this author. Like me, O’Connor found extremely distasteful the writing of select Southern authors. In O’Connor’s case, notes Gooch, the openly homosexual themes in works by Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams made her “plumb sick,” and for similar reasons she deemed Clock Without Hands by Carson McCullers the worst book she had ever read. Apparently, decadent sexuality was the mote in her eye that blinded O’Connor to legitimate talent. Perhaps profligate forgiveness similarly impairs my vision and blunts my enjoyment of an otherwise remarkable short story, setting me off on a scavenger hunt for technical glitches most readers disregard. But I can’t help myself: my revulsion, like O’Connor’s, is involuntary. •

Feature image by Melinda Lewis. Source images courtesy of UNC Greensboro Special Collections and Mateusz Drogowski. Feature images courtesy of Waiting for the Word, Alvaro Tapia, JR P, Will, Brent Payne, and Iowa Digital Library via Flickr (Creative Commons).