Every place has a rhythm. You must echo that rhythm in your writing. A character in New York City will not be as mellow as a character on the beach. A character in Wyoming will have a more expansive view than the character in Los Angeles. Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick might have had the grandest and most inclusive vision of all had he not permitted that vision to curdle into one single, obsessive focus. But that is Melville’s character; Melville himself is determined to make his novel as commodious and comprehensive as the ocean. Or consider E. M. Forster’s beautiful and foresighted A Passage to India, in which the English author dissects the tensions between native Indians and their British rulers.

Although we do not normally think of characters as props, we certainly can do so, at least for the duration of this essay. They are props in relation to other characters. Anything within reach of the place you have chosen may serve as a prop. The gun on the mantel Chekhov spoke of — the one that has to go off before the story ends — is a prop. The cold beer on the kitchen table is a prop. The apron the waitress wears is a prop.

Cherry on Style

When is a prop not a prop? When it’s not doing anything to further the story. On the whole, we don’t want to clutter our stories with meaningless objects. Yes, there are red herrings and MacGuffins, and some use can be got out of them, especially in detective stories and thrillers, but literary fiction is not about coaxing the reader into dark corners or dead ends. Serious literature usually intends to shine a light on the mysterious, the obfuscated, the entangled, and the overlooked.

William Faulkner’s story “That Evening Sun” (sometimes “That Evening Sun Go Down”) is a heartbreaker. The place is apparent in the first lines:

Monday is no different from any other week day in Jefferson now. The streets are paved now, and the telephone and the electric companies are cutting down more and more of the shade trees — the water oaks, the maples and locusts and elms — to make room for iron poles bearing clusters of bloated and ghostly and bloodless grapes, and we have a city laundry which makes the rounds on Monday morning, gathering the bundles of clothes into bright-colored, specially made motor-cars: the soiled wearing of a whole week now flees apparition-like behind alert and irritable electric horns, with a long diminishing noise of rubber and asphalt like a tearing of silk, and even the Negro women who still take in white peoples’ washing after the old custom, fetch and deliver it in automobiles.

That’s a pretty exhaustive description of the town, but now Faulkner goes on to describe what the town was like 15 years earlier, bringing us closer to the story he is about to tell. We see the washerwomen in Negro Hollow:

But fifteen years ago, on Monday morning the quiet, dusty, shady streets would be full of Negro women with, balanced on their steady turbaned heads, bundles of clothes tied up in sheets, almost as large as cotton bales, carried so without touch of hand between the kitchen door of the white house and the blackened wash-pot beside a cabin door in Negro Hollow.

“That Evening Sun” is a phrase from a black spiritual that begins, “Lordy, how I hate to see that evening sun go down.” The implication is that when the sun sets, death arrives. Thus a song, or perhaps we should say dirge, of death. The story is told by a young man named Quentin Compson. Nancy is one of the washerwomen.

Nancy would set her bundle on the top of her head, then upon the bundle in turn she would set the black straw sailor hat which she wore winter and summer. She was tall, with a high, sad face sunken a little where her teeth were missing. Sometimes we would go a part of the way down the lane and across the pasture with her, to watch the balanced bundle and the hat that never bobbed nor wavered, even when she walked down into the ditch and climbed out again and stooped through the fence. She would go down on her hands and knees and crawl through the gap, her head rigid, up-tilted, the bundle steady as a rock or a balloon, and rise to her feet and go on.

The point of view has switched from the young man to his earlier, nine-year-old self, and the story becomes less leisurely, more dramatic, less expatiating, more present. Nancy’s husband, Jesus (or Jubal), is violent and threatening. That Nancy is carrying a child, likely a white child, is more reason for Jesus to feel his manhood has been assaulted. But it is Nancy who is being literally assaulted: she is thrown into prison, made to lie like a dog on a pallet, left lying on a street after a white man, a Baptist, knocks out her teeth. She is afraid that her common-law husband, Jubal, sometimes called Jesus, is going to kill her. “I ain’t nothing but a nigger,” Nancy says, several times. Or, “I just a nigger. It ain’t no fault of mine.” Said quietly, but ringing in the mind like a wail, thick with fear and self-loathing. Although she is surrounded by people who want to do something for her, those people cannot grasp the depth of Nancy’s fears nor offer practical methods to diffuse her situation. The children babble about themselves, and their father thinks Nancy has worked herself up about nothing.

Mrs. Compson could (and should) have been generous enough to take Nancy in for the night, but no, she won’t allow Nancy to sleep in the spare bedroom; she has no sympathy for a black woman; she is a racist in a land of racists. Mr. Compson comes to collect the children, and Nancy, alone, waits for death to collect her. She is certain that Jubal is waiting in the ditch to kill her. She has paid the money for her burial insurance.

We don’t see the killing, but we hear her making “the sound that was not singing and not unsinging,” which is the sound of her moaning. Nancy’s aloneness in this story is extraordinary. Everyone in the story has failed her. It is as if she is stranded on an island in the sea where ships pass by but not one stops to take her on. And because she is black, we are dealt what I might call an emotional heart attack. The reader experiences the horror of her isolation and the horror of her fate. The story indicts us, charges us with our own injustice. Even if the reader is black, that indictment still holds. Callousness and indifference alienate caring.

A downbeat story, one would say, but enlivened by Southern accents and encompassing a world of tribulation as only a great writer can do. Welty called fiction “the heart’s field,” meaning that it is local, present, and surrounds us. You may have an epic novel in mind: Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, Stendhal’s The Red and the Black, Tolstoy’s War and Peace. But each big book is made of smaller localities, just as themes are made of notes. In each of them, the power of place is paramount.

Details we encounter include the blackened wash-pot and Nancy’s sailor hat. We learn that Nancy is “tall, with a high, sad face sunken a little where her teeth were missing.” We see a man who owes money to Nancy kick her in the mouth as she lies fallen on the street, and watch as “[s]he turned her head and spat out some blood and teeth.” We see the kids’ “toes curled away from the floor” because of the cold. When one of the characters advises Nancy to drink some coffee, we see Nancy blow on the hot liquid, “[h]er mouth pursed out like a spreading adder’s, like a rubber mouth, like she had blown all the color out of her lips with blowing the coffee.” This description may be taken as a prefiguration of her death.

The planet we live on is always changing. Maybe, nowadays, the local is becoming the global. So much of today’s literature is about India, or Africa, or China. We relish the diversity of cultures and histories and want to know them as well as we can before they are lost in a state of amalgamation. Yet if this seems depressing — the thought that in a few more centuries every place on earth will be just like every other place on earth — by that time we may be able to see our place as local. Louis D. Rubin, Jr. believed there will still be fictional characters “who grow out of an emotional relationship to the place and are manifestations of the imaginative experience of the locales in their creators’ own lives.”

So where can any of us find the fictional characters who “are manifestations of the imaginative experience of the locales in” our own lives?

Writers tend not to get around a lot. Hemingway did, Lawrence of Arabia did, Peter Matthiessen did. But most of us sit at a desk, tapping on a computer or making tiny comments on galley proofs. Even as the writer looks to anchor her work to place, her work provides that place with a sense of itself. Wallace Stegner compared that anchoring to a coral reef. The relation is symbiotic and over time it can become difficult to distinguish between the place and what has been written about it. Elizabethan England is Shakespeare — and Ben Jonson and Christopher Marlowe. Suburban 19th-century France is Flaubert. The American South is Faulkner, Welty, O’Connor, and many other writers. As Stegner put it, “No place is a place until things that have happened in it are remembered in history, ballads, yarns, legends, or monuments. Fictions serve as well as facts.” Or one might say that art and reality are in cahoots, each serving the other. •

This is part II of “Whatever Happens, Happens Somewhere.”

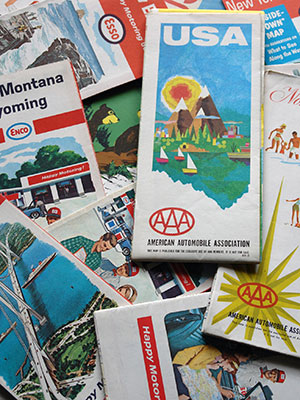

Photo by H is for Home via Flickr (Creative Commons)