Can technological progress be stopped? That is the question the Luddites asked 200 years ago in England. They did more than just ask the question — they tried to stop technological progress, physically. The Luddites were not particularly sophisticated in their methodology. Their main idea was to smash things. Their favorite things to smash were stocking frames. Stocking frames are machines used to knit. The first stocking frames were invented in the late 16th century. But stocking frames really came into their own at the beginning of the 19th century, with automation. That’s when the industrial revolution was swinging into high gear. The new machines being built in northern England in the early 19th century were transforming the textile industry from one that required highly skilled labor into an industry that required almost no skill at all. A person could be trained to operate a stocking frame in a few hours. Knitting — once a well-paid occupation — was fast becoming a low-wage affair.

According to legend, a young kid named Ned Ludd had smashed up a couple of stocking frames some time in the late 18th century. The Luddites of the early 19th century took up Ludd’s name and cause. They began smashing up factories and, occasionally, killing people. They also wrote letters to politicians and factory owners threatening they would kill them or otherwise make serious trouble. A typical Luddite letter, this one to Henry of Leicester, reads as follows:

It having been presented to me that you are one of those damned miscreants who deligh [sic] in distressing and bringing to poverty those poore unhappy and much injured men called Stocking makers; now be it known unto you that I have this day issued orders for your being shot through the body with a Leden Ball…

(From Writings of the Luddites, edited by Kevin Binfield)

By 1813, the Luddite rebellion had become serious enough to bring out the army. With this development, the Luddite rebellion could not last very long. Luddite leaders were rounded up and well-publicized trials conducted. Some called them show trials. The army and the authorities restored order. By 1816, there was no longer a Luddite movement to speak of.

But the legend lived on. Something about the Luddites had captured the popular imagination. The attention wasn’t always positive. Calling someone a Luddite became synonymous with calling him or her a reactionary. The ineffectiveness of the Luddite rebellion probably helped in this assessment. How was smashing up stocking frames going to defeat the greater social and historical forces that had led to automated stocking frames in the first place? The Luddites, so the thinking goes, were out of their league. The development of 19th century industrial capitalism was not going to grind to a halt because of few guys in Leicester had wrecked a couple of machines. Luddism, then, is a movement of futility. The Luddites were buffoons who mistook machines for enemies and tried to halt historical processes that were unstoppable.

Or maybe not. Plenty of left-leaning historians and social scientists have, in the last generation or so, tried to rehabilitate the reputation of the Luddites. The influential and recently deceased historian, Eric Hobsbawm, wrote a famous article in 1952 called, “The Machine Breakers.” In the article Hobsbawm explained that, while it may have been futile in one sense, the Luddite rebellion was an important episode in the early history of organized labor and attempts to improve the lot of the working class. Hobsbawm coined the phrase “collective bargaining by riot,” as a concise and memorable summing up of how he thinks we ought to think about the Luddites. Hobsbawm pointed out that machine wrecking actually did lead, in many instances, to wage increases and other concessions from employers and the government. In none of these cases, Hobsbawm argues, “was there any question of hostility to machines as such. Wrecking was simply a technique of trade unionism in the period before, and during the early phases of, the industrial revolution.”

The Luddites, then, were pragmatists. They were proto-trade unionists. They were fighting for their rights and their livelihoods in the only way that was available at the time. Their cause was not futile; Luddites were not machine-obsessed lunatics trying to halt the march of history.

And yet, there is something mad about Luddites. However much they were engaged in “collective bargaining by riot” the Luddites were also motivated by a magical figure of myth and legend — King Ludd himself. Thomas Pynchon, in a 1984 article called “Is it OK to be a Luddite,” explored this legend of King Ludd. Pynchon wrote:

But the Oxford English Dictionary has an interesting tale to tell. In 1779, in a village somewhere near Leicestershire, one Ned Lud broke into a house and ‘in a fit of insane rage’ destroyed two machines used for knitting hosiery. …By the time his name was taken up by the frame-breakers of 1812, historical Ned Lud was well absorbed into the more or less sarcastic nickname ‘King (or Captain) Ludd’, and was now all mystery, resonance, and dark fun: a more-than-human presence, out in the night, roaming the hosiery districts of England, possessed by a single comic shtick — every time he spots a stocking-frame he goes crazy and proceeds to trash it.

Futile, comic, ridiculous, dark, crazy. These are words bound up, inexorably, with what it is to be a Luddite. The dark, futile, craziness of the Luddites can’t be explained away by putting them in historical context. Proto-trade unionist pragmatists many of them may have been. But the Luddites were on a mad romp against history, against progress, against time itself.

•

There is a famous passage from Walter Benjamin’s “Theses on the Philosophy of History” where he is discussing an event from the July Revolution, France 1830. Benjamin writes:

Qui le croirait! on dit,

qu’irrités contre l’heure

De nouveaux Josués

au pied de chaque tour,

Tiraient sur les cadrans

pour arrêter le jour.

[Who would’ve thought! As though

Angered by time’s way

The new Joshuas

Beneath each tower, they say

Fired at the dials

To stop the day.]

(translated by Dennis Redmond)

It is absurd, of course, to think that the day was going to be halted by shooting at the clocks. It would take something divine, something outside of history altogether to stop time in that way — thus the reference in the poem to Joshua. Joshua is the Old Testament figure who, as the Israelites are engaged in a great battle at Gibeon, prays to God that the day might be stopped so that the Israelite victory can be complete. “Sun, stand still at Gibeon, and moon, in the Valley of Aijalon,” Joshua commands, “And the sun stood still, and the moon stopped, until the nation took vengeance on their enemies.”

This is something the Luddites would have understood. You can imagine King Ludd uttering a prayer like this, to stop the sun and the moon. Indeed, many of the participants of the July Revolution in France were the weavers who operated the Jacquard looms. Perhaps one of those people shooting at the clocks in 1830 was a disgruntled French textile worker. These workers were in the same position as the stocking framers of the Luddite rebellion. They were being pushed into poverty and degradation by the technological progress of the industrial revolution. All of these workers were trying to figure out what to do in the face of the tremendous change being wrought by the industrial revolution in early 19th century Europe.

Benjamin’s point in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History” is that there are two ways to confront technological progress. One way is to accept it and to try to mold it to your own benefit. This is what Hobsbawm thinks the Luddites were doing if you look at their actions in the sober light of historical analysis and ignore all the crazy myths and legends. The other way to confront progress is to deny that it is progress at all. In his “Theses,” Benjamin wrote:

There is nothing that has corrupted the German working-class so much as the opinion that they were swimming with the tide. Technical developments counted to them as the course of the stream, which they thought they were swimming in. From this, it was only a step to the illusion that the factory-labor set forth by the path of technological progress represented a political achievement.

Walter Benjamin’s sentiment is a Luddite sentiment, though it is not often recognized as one. King Ludd was the laborer who refused to go into the factory under any condition. He roamed the countryside, preferring his smashing and his “comic shtick,” as Pynchon called it, to the path of technological progress. The Luddites wanted to get out of the stream altogether. They had become suspicious of history. Maybe, they had even become suspicious of time itself. Or they imagined that an entirely different order of time was possible.

In the “Theses,” Benjamin wonders whether there isn’t a root conflict between time that is measured in calendars and time that is measured by the clock. Clocks count out the same units of time in the same way hour after hour, day after day, year after year. They assume that time is homogenous, that 12:13 PM on one day is exactly the same unit of time as 12:13 PM on the next. Calendars, however, pick out certain days as fundamentally different from other days. A holiday, for instance, is a date that has more similarity with that same date a year ago, and with all the past years that it has been celebrated, than it is like the day that immediately precedes it on the calendar. Calendars make time lumpy, whereas clocks make time smooth. “The calendar,” Benjamin writes, “does not therefore count time like clocks.” If you are suspicious of the notion of progress, argues Benjamin, then you ought to be suspicious of the smooth time of the clocks as well.

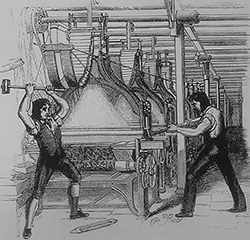

It has been said that King Ludd resembles figures like Robin Hood and King Arthur. That is to say, he is a figure who cannot really be placed within history. He exists, if at all, as a mythological figure standing right next to history, touching upon it without being subject to its flow. Like Robin Hood or King Arthur, King Ludd has become an immortal of sorts, no longer subject to time, no longer subject to the normal rules of life and death. In the most famous “picture” of King Ludd, from a drawing in 1812, the King seems to be wearing a dress. Indeed he is. The Luddites would often put on dresses in their mad romps through the English countryside, smashing up stocking frames. There was an air of Carnival about the entire affair, as if all the normal rules of life were being held in suspension. Just imagine that it is the winter of 1813. You can see the Luddites descending on a factory in your mind’s eye. Their colorful dresses are swirling about as they bring their sledgehammers down on the new machines.

They were attacking the machines, but they were also trying to smash themselves out of the world they lived in. They were trying to halt the sun and the moon. They were trying to freeze the time of the clocks. They were trying — in words Benjamin could very easily have applied to the Luddites — to “explode the continuum of history.” • 16 January 2013