It is like the message above Dante’s Gates of Hell. Abandon all hope, ye who enter here. Except that we are not entering hell, we are entering an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The message at the Gates of MoMA is in the form of a question. It asks, “Must we not then renounce the object altogether, throw it to the winds and instead lay bare the purely abstract?” The writer of the message is neither God nor Satan. He was a human being, and from Russia. His name was Wassily Kandinsky.

- “Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925” Through April 15, 2013. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. “Kandinsky 1911-1913” Through April 17, 2013. The Guggenheim, New York.

The attempt to answer Kandinsky’s question led to a transformation in painting the implications of which are still being felt today. The transformation was Abstraction. Painters, just a few years prior to Kandinsky, happily portrayed human beings and animals and landscapes and historical events. After Kandinsky, pure forms and shapes and colors took over the canvas. This was a shocking and more or less unprecedented development. It took the art world by storm and carried the oft-bewildered public along with it.

The current show at MoMA, “Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925,” tracks the developments in painting over those 15 tumultuous years. The question that lingers behind the show is: “Why did they do it?” The answer is to be found on the canvases, and also in the writings and comments that are left behind by many of the early pioneers in abstract painting. Abstract painting was an attempt to paint the Absolute. Kazimir Malevich, the Russian Suprematist painter and early practitioner and theorist of abstract painting proclaimed, “I have broken the blue boundary of color limits, come out into the white; beside me comrade-pilots swim in this infinity.” The majority of early abstract painters felt a version of Malevich’s glee. They were getting rid of the constraints of figurative painting. They were moving past false appearances and entering the domain of Truth. Painting in the abstract was a way of painting the true reality of the world, the real essences that are obscured in our everyday perception. Robert Delaunay, another pioneer in abstract painting, said that, “Direct observation of the luminous essence of nature is for me indispensable.”

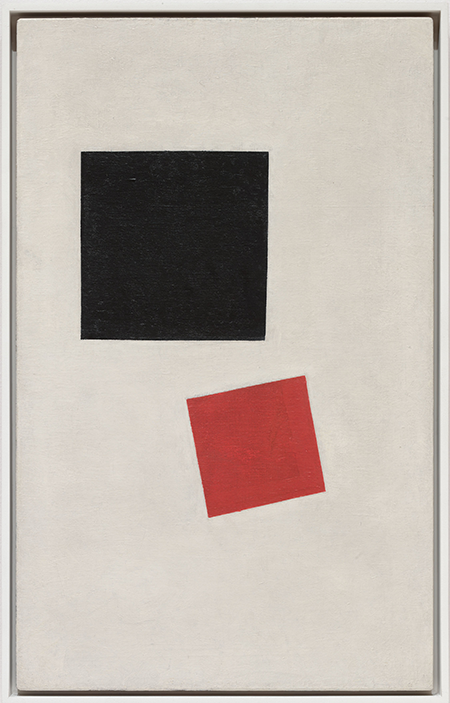

“Painterly realism of a boy with a knapsack color masses in the 4th dimension,” Kazimir Malevich (1915)

The “luminous essence of nature” was composed, for Robert Delaunay, of two fundamental things: light and color. Sunlight falling on a patch of grass, for instance, reveals the color green. But the color green is, in the standard color theory of Delaunay’s time, a mixture of the primary colors blue and yellow. So, a study of the color green becomes a study in the primary relationships between the colors that make up our visual experience of the world. Delaunay’s early paintings are such color studies. Blocks of primary and secondary colors bump up against one another in primal shapes and forms. These are the building blocks of the world we experience in normal life. You could almost say that Delaunay is playing God, messing around with the foundational stuff of the universe to uncover fundamental truths. It is not so surprising, then, that Malevich says of his own studies in light and shape and color that, “Every real form is a world. And any plastic surface is more alive than a (drawn or painted) face from which stares a pair of eyes and a smile.”

For this reason, it could be argued that the most important precursor to abstract painting was not any painter or school of painting, but a man named Ogden Rood. Rood was a physicist interested in color theory. In 1879, Rood wrote a book called Modern Chromatics, with Applications to Art and Industry. Rood pointed out that our perception of colors in all their variance and blending is actually the result of bits of contrasting primary color very close to one another. We think we are seeing green, but we are actually seeing the effect of a contrast between blue and yellow (there were important debates at the time as to whether the primary colors were red, yellow, and blue, or red, green and blue but the essential point about contrast and blending were the same). Neo-Impressionists like Seurat developed this insight in the late 19th century into the techniques of pointillism. Seurat was able to create entire canvases of tiny unconnected dots. From a short distance, the human eye picks up the contrasts in the color and blends them together to create a coherent scene. What up close is merely an unconnected chaos of colored dots becomes, from a few feet away, the scene of a Sunday afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

The difference between the Neo-Impressionists and the Abstract painters is in the goal. The Neo-Impressionists took Ogden Rood’s insights and used them to build up a visual picture of reality as we see it in everyday life. Seurat’s paintings are always, as long as one stands far enough away from the canvas, recognizable scenes from daily life. The abstract painters wanted to go one step further. They wanted to plumb the depths of essential reality. They wanted to show us the truths behind appearances, but only the truths, to give us a look at the relationships of color before they become something recognizable. Color, they thought, comes before objects.

There was an element of scientific inquiry in this approach to abstract painting. Ogden Rood was, after all, a physicist. Rood’s theory of colors was based on what were, at the time, the most advanced studies and experiments in the behavior of light. Robert Delaunay was perfectly comfortable saying things like, “nature engenders the science of painting.” But science, for most of the early abstract painters, was not an end in itself. Science gave us a look into the true nature of reality. Seeing the essential relationships of color was like looking at the universe through the eyes of God. Abstract painting, therefore, was taking scientific discoveries and using those discoveries in the service of the spiritual. Most of the abstract painters celebrated in the show at MoMA thought of their work in this way. They saw themselves as looking into the soul of the universe through the eyes of God — with the help of Ogden Rood.

Wassily Kandinsky was probably the clearest about this relationship between the optical science of abstract painting and its spiritual consequences. There is a small show at the Guggenheim Museum right now (“Kandinsky 1911-1913”) that, like the larger show at MoMA, portrays Kandinsky as a key figure in the emergence of abstract art. The show includes pages from his book On The Spiritual in Art, from 1911. There are also works in the show by Robert Delaunay and Franz Marc, two of the artists who most directly applied Kandinsky’s theories of color and essence. Kandinsky was keen to show that contemporary developments in color theory were opening up new possibilities in man’s relationship to the divine. Kandinsky became a follower of Theosophy and the infamous Madame Blavatsky. Madame Blavatsky once said, “The chief difficulty which prevents men of science from believing in divine as well as in nature Spirits is their materialism.” Kandinsky saw his art as science, minus materialism, plus spiritualism. And this is exactly what Kandinsky argues in his book. In his Introduction, Kandinsky wrote, “Our minds, which are even now only just awakening after years of materialism, are infected with the despair of unbelief, of lack of purpose and ideal.” The job of abstract art, for Kandinsky, was to break through that materialism using the tools of color theory derived from physics. Painting, for Kandinsky, hitherto lacked the ability to reveal inner essences and real spirit. Kandinsky dismisses art that is “a mere imitation of nature which can serve some definite purpose (for example a portrait in the ordinary sense) or a presentment of nature according to a certain convention (‘impressionist’ painting)…” His abstract art is going to do more. “Today,” as Franz Marc wrote in agreement with his friend Kandinsky, “we are searching for things in nature that are hidden behind the veil of appearance… We look for and paint this inner, spiritual side of nature.” In On The Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky describes the life of the spirit as it is represented in the figure of the triangle.

“Color study — squares with concentric rings,” Vasily Kandinsky (1913)

One can feel slightly embarrassed by Kandinsky’s adherence to Theosophy, by Delaunay and Marc’s painfully sincere statements about the spirituality of their canvases, by Malevich’s outbursts as he dashes into the white space of pure infinity, by Piet Mondrian’s mushy claims that abstract art is the emotion of beauty. But that is what the abstract artists told everyone they were doing. And that is what they did. They were worshiping truth and beauty. They were engaged in a spiritual practice. These abstract paintings are meant to be viewed in something of a religious manner.

The contemporary world, however, does not have ears to hear this message, nor eyes to see it. The story that MoMA wants to tell about the birth of abstraction, and the story being told by many of our critics, has nothing to do with what the abstract artists were actually doing. Kandinsky, Delaunay, Kupka, Malevich, Mondrian. These men are mysterious to the contemporary mind. The instinct today is to brush the stuff about spiritualism and the absolute under the rug. It only makes people nervous.

“Localization of graphic motifs II,” František Kupka (1912-13)

MoMA, therefore, focuses on early abstract painting as primarily a negative movement, a movement that was rejecting the art that had come before. Thus the quote they chose for the front gates: “Must we not then renounce the object altogether, throw it to the winds and instead lay bare the purely abstract?” In that quote, Kandinsky is speaking about the need to reject the object, to throw it away. But imagine what a different impression would be made if the quote above the gates was from Kandinsky’s On The Spiritual in Art, where he writes: “It is evident therefore that colour harmony must rest only on a corresponding vibration in the human soul.”

Of course, even with a quote like that, the spiritual nature of early abstract art would not be palatable to many. In his review of the show at MoMA for The New Yorker, art critic Peter Schjeldahl wondered:

What possessed a generation of young European artists, and a few Americans, to suddenly suppress recognizable imagery in pictures and sculptures? Unthinkable at one moment, the strategy became practically compulsory in the next. Many of the artists had answers — or, at least, they cooked them up. The trailblazing Wassily Kandinsky and the bulletproof masters of abstraction, Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich, doubled, tortuously, as theorists. They initiated what would become a common feature of determinedly innovative art culture to this day: the simpler the art, the more elaborate the rationale.

It is unimaginable to Schjeldahl that Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich, or any of the artists could be doing anything but “cooking up” crazy theories when they start talking about art and spirituality. Jerry Saltz, in his review of the MoMA show for New York Magazine, argues that the show “will still leave general audiences in the dark about why abstraction came into being. But careful observation reveals how powerful abstraction can be, how it is still a tool that circumvents language, disrupts identification, dissolves narrative, delays the crystallization of meaning, and becomes a reality unto itself.” Kandinsky would probably agree that abstract painting “becomes a reality unto itself.” But the idea that it is meant to “delay the crystallization of meaning,” would have confused and upset him. Early abstract art as Kandinsky understood it was meant to crystallize the very heart of meaning, not delay that crystallization.

Disrupting identification, dissolving narrative, delaying meaning — these are all contemporary concepts applied backwards to early abstract art in the inability to confront these paintings as they were meant to be confronted. Either these paintings are giving us the absolute or they aren’t. If these painting do not reveal the essential nature of reality than at least have the respect (one can hear the early abstract painters begging from across the decades) to credit us with a genuine failure.

A few years ago, the noted art critic Donald Kuspit wrote an article called “Reconsidering the Spiritual in Art.” Kuspit argued — bravely and against contemporary sensibility — that we ought to take Kandinsky seriously as precisely the spiritual artist he claimed to be. “How many works of art made today,” Kuspit asked, “require a second glance? There are no doubt works that seem emotionally powerful, and even deep, but rarely does one find a work in which the emotion and the medium seem one and the same.” That is the crucial accomplishment of early abstract art. The emotion and the medium are one and the same. Looking at one of Malevich’s great paintings like “Black Cruciform Planes: (1915) or a Mondrian like “Lozenge Composition with Yellow, Black, Blue, Red and Gray” (1921) the oneness of emotion and medium seems obvious. True reality sub specie aeternitatis is staring at us right there on the canvas. We, alas, are too blind to see. • 4 February 2013