16 years ago a mail carrier with the cheerful name of Martha Cherry was fired. She was 49-years-old, and had been with the U.S. Postal Service for 18 years, delivering mail by foot in Mount Vernon, N.Y., in Westchester County.

Cherry was let go after her superiors determined that she walked too slowly. “You were observed on June 9, 1997, to walk at a rate of 66 paces per minute with a stride of less than one foot,” the condemning report charged, adding the detail that her “leading foot did not pass the toe of [her] trailing foot by more than one inch.” The upshot? She took 13 minutes longer than necessary to walk her route.

The flap was, essentially, over whether mail — that is, information — should move at three miles per hour or three-and-a-half miles per hour. And it all seems tremendously quaint now — post offices are being shuttered almost daily, regular Saturday mail delivery may cease next August, and the postal service is hemorrhaging staggering amounts of money — last year it posted a deficit of $16 billion. Mail moving a half-mile per hour slower was not responsible for this.

Commerce and communications are rapidly shifting to other venues, with no relief in sight. The entire postal system, which was established by the Second Continental Congress in 1775, now looks to be following the trajectory of the Pony Express, albeit far more slowly. That short-lived if legendary service closed down in 1861, just two days after the transcontinental telegraph conveyed its first messages. Ponies were instantly rendered obsolete.

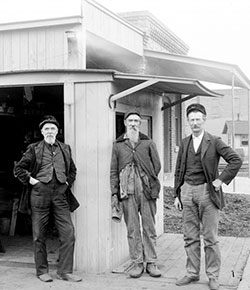

Unites States Post Office, Rural Carrier Howard T. Smith (c. 1910). Courtesy of the IMLS Digital Collection and Content.

The Internet and FedEx and UPS are today rendering mail carriers obsolete. The decline of the post office and its smartly uniformed employees will provoke a certain nostalgia for many of us. It recalls a time of handwritten birthday cards, an era before Facebook birthday greetings from people we don’t really know, filled with exclamation points we don’t really need.

Yet the decline also marks a more significant historic moment — we’re nearing the end of the long divorce proceedings between information and the simple act of walking.

Walking is information. When we first began to walk upright, say, five million years ago, it allowed us to expand our range, greatly increasing the distance we could travel daily from when we were knuckle-walkers and tree-loungers. Then, say, a million or two years later, our brains expanded and our memory vastly improved. This gave us quicker, more accurate access to essential information, such as the location of shelter and food.

Then we found we had the capacity to create symbols to permanently capture information, which we could convey simply by hand-carrying inky scratches on sheet of papyrus or bark. One historian has speculated that the sport of long distance walking had its roots in information delivery. “The earliest ‘pedestrians’ were probably ancient Greek and Roman foot messengers,” writes historian of athletics Robert Crego, who noted that these couriers would walk and run as many as 60 miles at a go to deliver important messages.

Then came Gutenburg and his printing press and information exploded and we couldn’t carry it all ourselves or entrust it to a few couriers. So we saw the rise of a modern information conveyance system that facilitated what scholar Robert K. Merton called “intercourse in the domain of thought.”

As nations developed and became more sophisticated, they set up elaborate postal networks to ensure the frictionless movement of information, in large part by marshaling a network of walkers. As recently as a century ago, the conveyance of information was still considered a fairly heroic human endeavor. Temples were built to honor the carriers, and post offices occupied grandly columned structures on squares and village greens. (For the past half-century, new post offices tend to be unedifying, vinyl-sided boxes built at the edge of town, as if they were embarrassments best kept from sight.)

The grandest temple was arguably the James Farley Post Office in midtown Manhattan, built in 1912 and designed by McKim, Mead and White. It’s the one inscribed with a heroic quote adapted from Herodotus’s description of Persian Empire couriers: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” It could be a slogan of the Justice League, or any other comic book confederation. Postmen were our superheroes.

As society grew soft with the rise of the car, letter carriers were even more heralded for their superhuman vigor. A 1907 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer entitled “Walking a Vanishing Art” lamented the degeneration of “civilized man” and decried “people who are always traveling on wheels.” “The only remaining sturdy types,” the writer averred, were “the patrolman, the postman, the lamplighter and others who are obliged to walk much.”

Teams of postmen often competed in popular walking competitions in the late 19th century. (Given the Lance Armstrong imbroglio, perhaps the post office should have avoided any dalliance with newfangled bicycles.) And individual postmen were regularly hailed in newspapers for the distances they’d had accumulated on foot during their appointed rounds. Typical was this headline in the Duluth News Tribune in 1915: “Five Times Earth’s Girth is Traveled by Postman; Duluth Man in Service Twenty-Eight Years, Invents Self-Adjusting Wrench.” (The “wrench” park: not so typical.) One London letter carrier, Thomas Phipps, was singled out for having walked 440,000 miles in between 1840 and 1898. Three decades earlier, one famous long-distance competitive walker named W.H. Smythe competed under the track name of “The American Postman.”

The starts and finishes of these walking competitions were frequently at the post office itself. Post offices were more than just depots for the transfer of love letters and Sears catalogs. They were cairns — the place from which distances were marked. Postmasters were considered the arbiters of distance, the keepers of the maps, the people who knew exactly how far their mail carriers walked and thus exactly how far it was to the edge of town and back.

The post office still employs a small army of walkers. According to the USPS web site, some 8,000 employees depart directly from a post office on foot to deliver the mail; another 75,000 first drive to a neighborhood and then walk.

Hard figures are elusive, but the average mail carrier appears to walk about eight to 12 miles a day, which according to some paleoanthropologists, is about the range we humans have evolved to cover on a daily basis before we gave that up in favor of gas-powered mobility. Essentially, we all evolved to become mail carriers, to walk long distances every day in conveying information.

Information today moves at the speed of light. And while we thrill at the idea of boosting our home data connections to 60 MBPS, I don’t think it would be a bad thing if more of us embraced slow information, and continued to convey it by foot. This would have the benefit of allowing information time to cool down as it traveled, making it less scalding upon arrival, while granting us sufficient time to digest what we’ve learned.

The postal carrier is one the great figures in our national development, like the Minute Men or the Doughboys. But they are increasingly an anachronism, soldiers on the front lines with bayonets rather than lasers.

So, as the post office continues its gradual slide into irrelevancy, I’d like to propose a memorial to Martha Cherry, the mail carrier with the one-foot stride. Perhaps a nice bronze statue. She represents not only what’s sure to be a fading sight along our streets and boulevards in the years ahead, but recalls an era when information moved with an appealing lack of urgency, and a time when information was conveyed by superheroes. • 18 February 2013