What’s in a broom? In a small room at the Shaker Heritage Society in Colonie, New York, just across the road from the Albany International Airport, is a cloudy glass case housing a flat-bottom broom and a handful of other Shaker inventions: an oval box, a custom dress form. But the Shakers invented so many things that no glass case is big enough to hold them all: the circular saw Tabitha Babbitt re-imagined while spinning on her loom, the wheel-driven washing machine, vacuum-sealed tin cans, the rotary harrow, metal pens, a new type of fire engine, a self-acting cheese press, a chimney cap, a machine for setting teeth in textile cards, a threshing machine, a pea sheller, a butter worker, a dough-kneading machine. And there were still more innovations. The Shakers were the first major producers of medicinal herbs in the U.S. and the first to sell seeds in paper packets (each packet individually cut, folded, pasted and printed by the Shakers). We don’t realize Shakers invented these things, but we know the products well.

The Shaker Heritage Society in Colonie is a museum only nominally. It is more of a preserved ruin, a ghost town in miniature. The buildings are equal to anything in Detroit, with peeling insides and dead vines crawling up the windowpanes. The museum staff has planted an herb garden gone dead for the winter within the foundations of the building that was once the Women’s Workshop. The gift shop manager tells me that Albany locals were using abandoned Shaker furniture for firewood during the Depression and that, for a while, the site was used as a Catholic nursing home whose owners ornamented the austere Shaker meeting house with chandeliers and candelabras and altars.

The Shakers were not always so forgotten. For the many American communitarian societies that have come and gone over the last few centuries, the Shakers were once near the top of the food chain. Somehow the Shakers managed to strike a balance between living isolated from the pressures of the modern world and living with it. As a result, they had more of an impact than most communitarian societies. They established 19 communities before all was done, with 6,000 members at their height. Other Utopian dreamers — the Fourierists, the Oneida Perfectionists, the Koreshan Unity, and the Fruitlands colony — are now the stuff of rumors, their radical experimental spirit woven invisibly into the radical experimental identity of America.

It was at Colonie (then Niskayuna) that leader Ann Lee and the first fistful of Shakers founded their American homestead in 1776. They had been essentially chased out of Manchester, England for rabblerousing a couple years prior. But in America, they could make manifest Lee’s vision of a community that would create heaven on earth. For Ann Lee, the timing couldn’t have been more destined. After establishing the colony at Niskayuna she went on a missionary tour of the Northeastern U.S., then in the throes of revolutionary war fever. She preached the dangerous message of peace — not to mention sexual and racial equality, the dissolution of traditional family structures, the condemnation of private property, confession of sins, celibacy, and isolation from the outside world. Ann Lee was preaching a new way of living. For her trouble, Ann Lee and her companions were harassed (physically, sexually and otherwise), jailed, and made the subject of scathing editorials. In other words, the Shakers made a name for themselves. They made a good number of converts too.

The Shakers are now known for austerity, especially in their design. In worship, however, the Shakers were anything but restrained. Shaker religious services were ecstatic chaos, full of hopping, writhing, trembling, singing, screaming, convulsing, and shaking (and this is how the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing got their nickname). The Shakers crowed like roosters and ran naked through the woods, seized with the spirit. Neighbors could often hear their rituals from miles away. How could such apocalyptic fervor spawn so utilitarian an object as the flat-bottom broom? Moreover, why was the humble broom such an important part of the Shakers’ gospel?

While living in mid-18th century Manchester, the young Ann Lee worked 14-hour days in a cotton mill. We don’t have much documentation about this time in Lee’s life. Suffice it to say, she knew well how the making of goods could be as meaningless and hard as it was necessary. The simple, clean, agrarian Shaker life was meant to be in drastic contrast with the crowded, anonymous, industrial life of Manchester.

Flattening the broom’s bottom seems like a small innovation. But before this the broom was little more than a bundle of twigs that moved dirt around the house. Flattening the bottom made the broom so efficient it’s hard to now imagine the broom any other way. The flat-bottom of the broom is as integral to the act of sweeping as it was integral to Shaker doctrine. Sweeping encapsulated the alienation of household labor. It was a solitary act, somewhat futile, usually done by women. So the Shakers turned the broom, literally and figuratively, upside down. By streamlining and improving daily chores, for both men and women, work could be more joyful, more expressive of the community. Leisure time would be increased. Cleanliness (next to godliness) was improved. The Shakers could be more self-sufficient, thus further insulated from the political and religious pressures of the outside world. In other words, to create new ways of living, the Shakers had to create new ways of working.

Shaker design — from invention and architecture to the way they ‘designed’ their religious rituals — were not just driven by economic necessity. They were living expressions of the gospel begun by Ann Lee and developed by her successors. One could think of the whole Shaker community — the way they ate, the way they worked, the way they prayed — as a dance, where every movement was considered, each element important to the whole. The tasks and tools of daily life are inextricable from the people who used them, the Shakers thought. They are expressions not just of how we work but how we live.

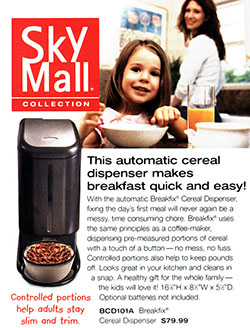

The contrasting symbolism along Route 155 seems almost intentional. On the right-hand side, an international airport, rental car stations, a private corporate airline called Million Air. On the left is Meeting House Road, abandoned home of the Shakers. These two sides of the road have nothing to do with one another, one might think. And yet, they do. The reason is SkyMall. Nowadays, when we think of inventions, many of us think of the SkyMall catalog, the wonder world of crazy objects in the seat pocket of most flights. A home cellulite smoother, a cat litter robot, a touchless sensor toilet seat, a waterfall soap saver, a plantar fasciitis sandal, an ultrasonic hand moisturizer, a talking dog collar, a bedbug sleeping cocoon, a nano-UV disinfection scanner, a personalized cell phone flask, a beer pager, something called a bracelet assistant — every object imaginable (and most could not be imagined by the average person) for improving our homes, our bodies, our work, our leisure, our lives.

No one understands what most of the objects in SkyMall are really for. But they are bewitching nonetheless. The SkyMall inventions are often outrageous in their promise to ease even the most microscopic tasks of daily life. The airplane, a place of discomfort and dependence, makes the lure of these inventions especially strong. Between the pages of SkyMall is the American desire for self-reliance so strongly expressed by the Shakers. The Shakers, too, saw the connection between convenience and independence.

Convenience, however, is a slippery slope — what begins as easing the burdens of daily life can end up in a feeling of increased dependence on comfort — even an alienation from our daily tasks. The Shakers understood this. They resisted the impulse of convenience for convenience’s sake. Shaker inventions were not meant to distract them from work. If the inventions made the workday easier, and ended it sooner, it was to increase time for communal leisure activity. Namely, for prayer. Shaker inventions — like all Shaker activities — were about improving the community. The Shakers were first and foremost social reformers. SkyMall inventions, on the other hand, are about self-improvement. You might say the Shakers and SkyMall represent two faces of the American psyche.

In his book Seeking Paradise: The Spirit of the Shakers, the theologian Thomas Merton wrote, “The peculiar grace of a Shaker chair is due to the fact that it was made by someone capable of believing that an angel might come and sit on it.” The connection between work and worship was a sentiment the Trappist monk felt close to. But Merton’s words also capture something essential about Shaker design. “Hands to work, hearts to God,” is a well-known epigram of Mother Ann Lee. Even more striking and poetic is her entreaty to “Do your work as if you had a thousand years to live and as if you were to die tomorrow.” The Shakers’ inventions were not only an expression of their social values, or about a moralistic attitude toward work. As Dolores Hayden wrote so beautifully in Seven American Utopias, “The Shakers visualized splendid heavenly cities while they built ascetic, earthly villages.”

…in the closed system of Shaker life, every physical design made possible a responsive, opposite spiritual action. To appreciate the straight chairs, one must know the whirling dances. To understand the rigid alignment of the buildings, one must envision members marching through their orchards or rolling woodlands singing of a procession in their Heavenly City.

Shaker inventions were the earthly made heavenly and the heavenly made accessible.

Various religious sects in 18th and 19th century America, so-called Millennialists, believed in an impending second coming during which Christ would reign on earth for a thousand years prior to the last judgment. The Shakers called themselves Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing because they believed that this time had already come, and in the form of an illiterate woman from Manchester. In short, work, for the Shakers, was meant to be done apocalyptically. As if your life depended upon it. This is what is meant by “Hands to work, hearts to God.” In the 215 years since Brother Theodore Bates flattened his broom’s bottom, there has been no meaningful innovation made to the broom, save electrifying it. For many tasks, the flat-bottomed broom remains the best tool and will remain so, conceivably, until the end of time. It’s hard to locate that everlasting quality within the objects that fill the pages of the SkyMall.

The Shaker Heritage Museum in Colonie sums up the Shaker legacy. The defunct village is emptier than the museum; the Shaker crafts gift shop is more popular than the village and museum combined. Most scholars agree that the Shaker movement declined due to the combined effects of the Civil War and the fact that Shaker-made products — not to mention Shaker beliefs — couldn’t compete with industrialized America. The modern world was no place for agrarian utopian communities. The celibate members got older and fewer, and today there are but three.

During their history, the Shakers attracted converts because of their awesome message: That every aspect of their daily lives could bring about the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth. That each day could be lived apocalyptically, not in the denial of mundane daily life but the total embrace of it. In their heyday, the Shakers offered a radical and convincing alternative to the modern industrial world they eventually, if reluctantly, came to embrace. The qualities that made Shakers a success in America seem impossible — asceticism, celibacy, the total abandonment of oneself to a community. The marketing of their crafts helped Shakers survive economically. It could have contributed to their downfall, too. As Thomas Merton wrote, “Cutting wood, clearing ground, cutting grass, cooking soup, drinking fruit juice, sweating, washing, making fire, smelling smoke, sweeping, etc. This is religion. The further one gets away from this, the more one sinks in the mud of words and gestures. The flies gather.” • 4 March 2013