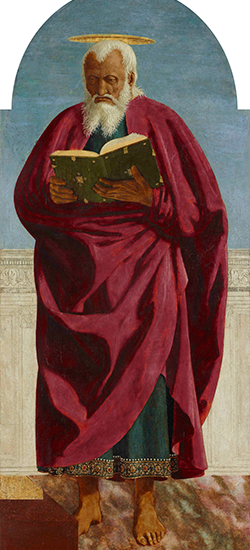

If you stand dead center, looking directly at Saint Augustine, his feet are in the wrong place. They are too far over to the right. This is questionable in terms of posture, and may be downright anatomically incorrect. It seems like an error by a painter who should have known better. But this painting is not meant to be viewed straight on. It is meant to be viewed from off to the right. That’s because this painting of Saint Augustine was once part of an altarpiece. That altarpiece no longer exists as an altarpiece. But several of the individual paintings from the altarpiece can be found in permanent homes at museums in Europe and the US. Standing directly in front of the original altarpiece in the year 1469, you would have turned your head to the left to gaze at Augustine. Today, you have to pretend that the painting of Saint Augustine was part of an altarpiece. You have to stand in front of Augustine and then take five or six steps to the right. Then you turn your head to the left. Performing that little maneuver — as you can at the Frick Collection in New York City now through May 18, 2013 — you’ll notice that Augustine’s feet line up nicely with his body. Indeed, the whole painting comes into proper view. The same thing happens with Saint John the Evangelist, who was originally on the other side of the altar. To look at Saint John correctly, you have to shift a few steps to the right of the painting. If you’re in the right spot, Saint John looks like he is turned toward you.

- “Piero della Francesca in America,”

Through May 19, 2013.

The Frick Collection, New York

The painter of these works is known as Piero della Francesca. He was born at the beginning of the 15th century and died the year Columbus sailed the ocean blue. Piero spent most of his life in his hometown, Borgo San Sepolcro. He made trips to Rome and other cities. But unlike other painters of the early Renaissance, his ambition did not drive him away from home in search of fame and fortune. He made art locally, mostly for the churches in his region. Many of his paintings are still in those churches and cannot be moved. It is for this reason that an exhibit of Piero’s art always creates a big to-do. The current exhibit at the Frick is no exception, especially since the exhibit brings together a number of works from Piero’s Sant’Agostino altarpiece that don’t often get to be in the same room, including the aforementioned paintings of Saint Augustine and Saint John.

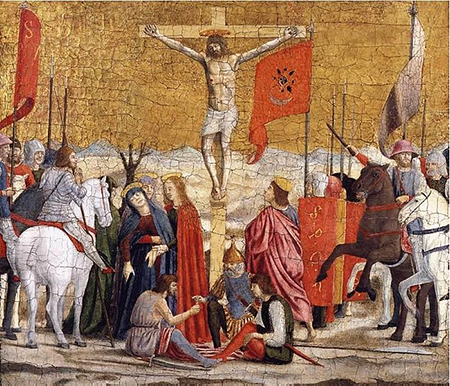

“The Crucifixion”

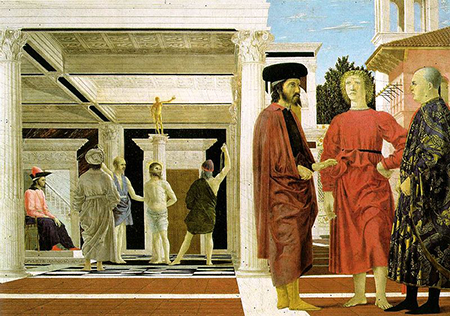

Another painting from the Sant’Agostino altarpiece depicts the crucifixion. This painting, now known as “The Crucifixion,” originally would have gone on the predella, the horizontal area at the front of the altarpiece. Much of the current high regard for Piero’s work is due to a comment once made about “The Crucifixion.” The influential critic and collector, Bernard Berenson, praised “The Crucifixion” as reminiscent of Cézanne. The comment by Berenson is not the idiosyncratic statement it might seem to be. Berenson compared Piero to Cézanne because both painters were interested in geometry. Cézanne always claimed that he was painting nature according to its essential geometrical forms. A plate of fruit was, to Cézanne, also a plate of spheres and cones. Looking at a Cézanne still life, you are meant to see both the fruit, and the essential geometry of the fruit. In Piero’s case, the geometry recedes into the background of the painting. Piero’s fruits and faces do not look overtly geometrical, but they could not have been painted without the complicated lines of perspective he used to construct his pictures. One of Piero’s most famous paintings (not shown at the Frick exhibit) is also one of the most complex painterly compositions ever made. The painting is known as “The Flagellation of Christ” (1458-60). In it, Christ stands against a pillar to the back left of the painting. Three men discuss something seemingly unrelated in the right foreground. The low viewpoint of the painting, the multiple sources of light, and the placement of Christ over in the corner make it a strange and mysterious work. Analysis of the painting shows that Piero used every trick in the book to paint it. “The Flagellation of Christ” is a tour de force in 15th century optical mathematics. Much of this work in mathematics and optics was done by Leon Battista Alberti, a contemporary of Piero. Alberti literally wrote the book (Della pittura) on how to paint using mathematical models of perspective. Alberti’s biggest insight was that, by viewing a painting as an “open window,” the painter could draw visual rays from the viewer to whatever was being look at through that window. Using principles of geometry, a painter had precise rules for creating the illusion of depth and distance for whatever he wanted to paint along the trajectory of the visual rays. No serious painter could ignore these new techniques. Piero, like Alberti, wrote books on perspective and was more revered by many in his time as a mathematician than as a painter. As a painter, Piero was putting his studies into practice, demonstrating the new theories of perspective. You might think that a painter obsessed with mathematics and problems of optics and perspective would create works that reflect a certain analytical distance. You might think, similarly, that a writer of abstract studies on painting would have little patience for the particulars. But here you would be wrong.

“The Flagellation of Christ”

The paintings that make up the Saint Agostino altarpiece have been displayed at the Frick with some attention to how they would have looked in church as an actual altarpiece. That’s appropriate since Piero was, in this case, using his theories of perspective to create a more effective altarpiece. An altarpiece is, after all, a tool for worship. It is a wooden structure that displays paintings of sacred scenes. It stands behind the altar in a church. The paintings of an altarpiece should, therefore, bring some focus to the altar and to the act of worship. Piero did that with his altarpiece. The panels portraying Saint Augustine and Saint John the Evangelist cannot even be appreciated as paintings unless you look at them from the proper angle. Piero painted them intentionally that way, and he had the technical skill to do so. Piero took the placement and perspective of each painting in the altarpiece seriously, down to the details. The gems on the bottom hem of Saint John’s garment were probably meant to catch the light from the devotional candles that would have been found at the base of the altarpiece. Likewise, the painting of Sant’Apollonia was clearly situated on the predella where light would have been coming onto the painting from the left, probably from a window at the back of the church. Ultimately, Piero was using his mathematical models to make the altarpiece look perfect from the perspective of the priest, who would be standing toward the altar in the act of worship.

We tend, today, to look at individual paintings in an altarpiece as if they are essentially easel paintings that just happen to have been placed in church and could just as easily be placed anywhere. Yet, there was no such thing as easel painting in Piero’s time. The whole point of putting a painting on an easel is that it becomes portable. With easel paintings comes the idea that paintings are important solely as paintings — that they can be appreciated anywhere. In the 15th century, paintings weren’t displayed individually, out of context, for the sheer sake of admiring them as paintings. The wood panel paintings of medieval altarpieces did eventually develop into the tradition of easel painting. But this didn’t begin to happen until the century after Piero’s death.

The paintings of the Sant’Agostino altarpiece were painted for that specific altarpiece and for that reason alone. A person looking to the altar at Sant’Agostino would have been drawn to it, as the lines of perspective that Piero had so perfectly worked out beckoned them forward. They would have stood below “The Madonna and Child” (now lost) at the center. They would have gazed to the right and to the left and been addressed almost personally by Saint Augustine on the far left and Saint Nicholas of Tolentino on the far right. Closer in: the saints and angels. Looking down: the smaller paintings along the predella add accent, flavor, and scriptural context to the central panel. Glancing around: the roundels, spandrels, pinnacles, and pilasters chime in with perfect harmony. You can almost hear, if you only try, the celestial spheres tinkling away in heavenly bliss as everything in Piero’s altarpiece locks into place with a geometric certainty that confirms the cosmic order.

These are not paintings so much as forms of experience. They are certainly not aesthetic objects as we now use the term. Piero’s paintings for the Sant’Agostino altarpiece are tools for worship. They are essentially geometric treatises locating and defining sacred space. Piero did not simply produce a number of random Christian images. He painted figures that situate the altarpiece in space and time, both in the worldly and spiritual sense. The Sant’Agostino altarpiece was not just in any church; it was an Augustinian Church — thus, the appearance of Saint Augustine. The saint on the far right panel of the altarpiece was a local saint. His name was Nicholas of Tolentino and he lived only about a century before Piero. Even more specifically than that, one of the paintings on the predella probably depicts Saint Leonard. According to local stories, Borgo San Sepolcro (Piero’s hometown) was founded by two pilgrims who brought a stone from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem in order to build a chapel for Saint Leonard. All of the paintings in Piero’s altarpiece focus us toward a specific place, a specific time, a specific history, and, finally, a specific act.

Admirers of Piero often say that his paintings seem somehow immobile, even if people are moving around in them. The art historian Kenneth Clark once called Piero’s battle scenes “somnambulistic.” It is also a widely held opinion that Piero’s paintings are extremely moving. How can something that doesn’t move be so moving? There is certainly an immobility to the Sant’Agostino altarpiece. The figures of the saints stand there with great reserve. It is as if they are waiting for us to enter into their world. We are the ones who are supposed to do the moving, not them. And that is the trick of it. Piero used his geometry and his lines of perspective to get us to move. That is why his paintings can feel so moving even though they portray figures of calm detachment. The paintings orient us. The perspective draws us along as we view the paintings. Literally, the paintings force us to stand in one place and not another. Figuratively, the paintings orient us by promoting contemplation, an orientation of the soul. These immobile works are instigators of motion. The motion in the paintings is the mathematical force of motion that, finally, moves us. • 19 March 2013