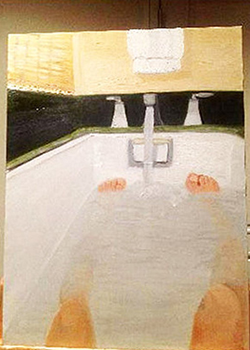

George W. Bush has finally found WMDs. That’s what a commenter on the website Gawker recently noted. But these WMDs are Watercolors Mostly of Dogs. George W. Bush, you see, has taken up painting. His favorite subject is dogs. It is said that he has already painted over 50 paintings of dogs. He also paints landscapes and, disturbingly, scenes of himself in the bath and shower. Luckily, these are not really nudes but mostly studies of his own feet.

The idea of George W. Bush, Painter has unleashed a great wave of amusement. Even Bush is in on the joke. He quipped that it will be hard for many people to accept him as an artist when they don’t even think he can read. An anonymous hacker hacked into Bush’s cell phone and then released the pictures Bush had snapped of the canvases he’s been working on. This inspired Bush himself officially to release photos of his paintings. For better or worse, George W. Bush has never been one to hide in shame.

The paintings are not nearly as bad as you might want them to be. In fact, they show some natural talent. Bush has picked up, in a relatively short period of time, the basics of handling a brush and depicting scenes in three-dimensional space. If nothing else, it’s one hell of an advertisement for the woman (Bonnie Floor) who taught him to paint.

Yet, the more you look at Bush’s paintings, the more you see a painterly sensibility. He has, for instance, an innate flair for perspective and point-of-view. Here’s a simple example:

In painting a house, your average beginning painter will approach the house straight on. They’ll paint a version of the square box with windows that you’ve seen countless times in children’s drawings. Bush painted his house using principles of linear perspective. He shows the house from an angle. The back of the house recedes into the distance. We get a sense of depth and a more interesting view of the house. Bush’s perspectival masterpiece to date is another painting of a house:

This painting includes a boardwalk leading down a hill. Again, Bush has got the perspective right. And he has picked an interesting point of view. The boardwalk sweeps down and practically spills right out of the painting at our feet. Not a Baroque masterpiece exactly, but Bush has a sense for the drama that can be generated with a few simple painterly techniques.

Bush also has a tendency to get on top of things. Take this little still life of a watermelon on a table:

I suspect Bush tried once or twice to tackle the watermelon head on and realized he wasn’t getting anywhere. But the floating-over-the-table viewpoint is quite satisfying. It allows us to see the watermelon’s most delightful attribute: its stripes converging at the top of the fruit. Or look at the painting of two dogs lying on the ground. Bush has captured something vulnerable and inept about indoor dogs. The viewpoint from above is what makes it work.

This skill for perspective has disturbed a number of critics who’ve recently commented on Bush’s painting. The thought goes like this: “Bush-the-President was terrible at seeing things from different points of view. But Bush-the-Painter seems to have a natural propensity to see things from different points of view. He was an arrogant and single-minded politician, but he seems to be a sensitive and flexible artist. How can this be?”

This problem got me thinking about Degas.

Degas spent quite a bit of time looking at landscapes, people, and animals from different perspectives. You might think this is true of all painters. But it is not. Some painters hate looking altogether. They struggle against the tyranny of visual perception. They don’t want to be forced to record their optical experience of the world. An obvious example is Piet Mondrian. You’ve seen Mondrian’s compositions: a few blocks of red, yellow and blue separated by black lines on a field of white. Mondrian didn’t want to paint from vision. He wanted to strip away the appearances, showing us the fundamental realities beneath the world as it is seen.

But some painters are excited by the simple act of looking. And Edgar Degas was most assuredly a looking painter. That is probably why he gave up Impressionism early on. There was a limit to how much Degas wanted to deconstruct the visual field. For a true Impressionist like Monet, all the things of the world could be reduced to patches of light and color. For Degas, the patches of light and color are only interesting insofar as they tell us more about the ballerina, the horse, or the bather who is the subject of the painting. Degas, in short, thought of himself as a Realist. Like any Realist, he was fascinated with the world as we directly apprehend it. Degas didn’t want to deconstruct the world; he wanted to reveal the world.

But just because you’ve declared yourself a Realist does not mean the job is easy. There are still plenty of important questions. If you’re a painter, you’ve got to decide what scene from the real world to portray and how you’re going to portray it. The fact that Degas so famously liked to paint pictures of pretty ballerinas has obscured something important about his paintings. Degas did not like artifice. He didn’t like prettiness for the sake of prettiness. He painted most of his ballerinas in the studio, practicing. He liked to catch them in awkward poses. He wanted to paint people unaware that they were being watched or who were in the midst of a mistake. He liked to paint people in moments when they’ve become lost in what they are doing, or are simply drifting in their own thoughts.

Degas often chose odd angles for his paintings. He would paint a ballerina or a bather from slightly above. Degas wanted to emphasize that the scene had not been staged for the benefit of the painting (even if it had been). For this reason, there is often a keyhole effect in Degas’ paintings, especially the paintings of bathers. Again, this is to emphasize that we are getting a glimpse of someone who does not know they are being glimpsed. We are looking in on a private scene.

The point of all this was truth. The central thought of any true Realist painter is this: “Reality looks and feels exactly like this painting.” Degas was obsessed with people in the bath because he felt people were most who they are alone in the bath. There’s no pretense in the bath. There are no lies. In your bath alone, you are just you. The opposite end of this spectrum is watching performers practice. Notice that in many of Degas’ ballerina paintings an instructor watches nearby, ready to pounce on any incorrect movement. Rehearsals are a great place to watch people moving quickly between states of great self-awareness, then forgetfulness, then tension, then calm, and so on. So, the bath and the ballerina practice hall turn out to be places of great truth, if for different reasons.

Degas spent a lot of time watching bathers and ballerina, waiting to grab just the right moment. He would crop these paintings in seemingly arbitrary or awkward ways. You could call this a ‘snapshot effect’. In some of his ballerina paintings, there are people in the foreground who seem to be in the way. Looking at the painting, you want to get on your tiptoes to get a better view. A Realist like Degas wants to find the best standpoint, the best perspective from which to reveal that great truth. The straight-on viewpoint is usually not the most revealing viewpoint. Truth, for the Realist, requires a sideways glance or a peep through the peephole.

Comparing the paintings of George W. Bush and Edgar Degas is an absurd undertaking if we are talking about quality. We would be comparing a hobbyist with one of the great masters. But I am not suggesting that we compare in terms of quality. I am suggesting that we can learn something about the Realist mind when we look at the art of George W. Bush as well as that of Degas. The Realist is often forced to the side, to the oblique angle, to the unusual vantage point precisely in his attempt to get at the truth. The truth of a scene doesn’t always reveal itself right away. The Realist must hunt for the right spin with great confidence. The Realist believes in his or her capacity to see rightly. The Realist cares nothing for multiple points of view. The Realist cares only for the correct point of view, the view that reveals the most truth. That is to say, Realists in painting (or in anything else) have an in-built arrogance. It is an arrogance born of the idea that Realists are uniquely able to see things the right way. Even if this means that they must climb up into the rafters and look down on a scene from a strange angle, the Realist is fundamentally convinced that his own point-of-view is the correct one.

Perhaps this begins to sound more like the George W. Bush we’ve all come to know and love (or love to hate). He paints like a Realist. And that is exactly how we would expect him to paint. Is it really so surprising that Bush’s Realist paintings show intelligence in eye and daring in execution? I leave it for others to decide. What is not surprising is that Bush paints more or less the same way he did politics. It is Realism through and through. The question is whether being a Realist is as good a thing for a politician as it can be for a painter. Degas, for instance, was an incredible painter. But Degas, partly because of the arrogance of his Realism, would have made a terrible President. • 28 April 2013