Marino Auriti kept Il Enciclopedico Palazzo del Mondo in the garage. It was stored in the back, past scores of Auriti’s paintings that hung salon-style (as his granddaughter remembers) nearly floor-to-ceiling over the garage walls, and past the array of car parts that lay on the cement. His paintings were mostly reproductions of photographs clipped from National Geographic and paintings of the Renaissance masters. Marino Auriti loved Raphael and Michelangelo and Leonardo.

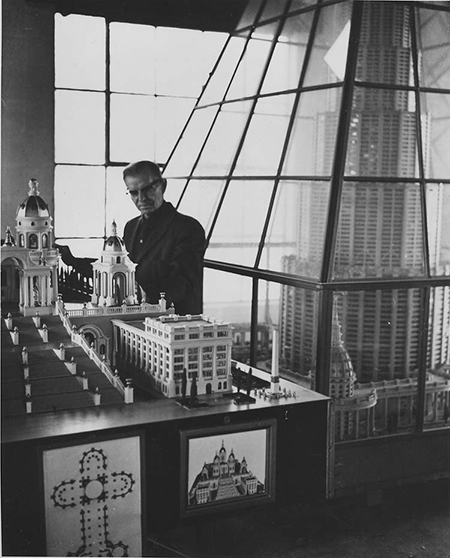

Auriti was a car mechanic by trade but architecture was his passion. The Italian-American immigrant began working on Il Enciclopedico in the 1950s, after he had retired. The sculpture Auriti kept in his garage-turned-studio had a footprint of 7 feet by 7 feet. In the center was a tiered tower about 11 feet high. The tower was surrounded by a tiny piazza, enclosed by columns. In each corner was a domed building. To make Il Enciclopedico Auriti used bits of wood, brass, plastic, and model-making kit parts. For the windows he used celluloid; for the balustrades, the teeth of hair combs. At the top of the tower was a television antenna.

But this sculpture was not itself Il Enciclopedico Palazzo del Mondo. It was only a model for the real Il Enciclopedico Palazzo del Mondo Auriti hoped to build. He specifically hoped to build it on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Marino Auriti envisioned a museum like none other, a monument to the entire history of human knowledge and invention, from the wheel to the satellite, “designed to hold all the works of man in whatever field, all discoveries made and those that may follow.” The Encyclopedic Palace of the World would be 136 stories — the tallest building in the world (at that time). The main building would have 24 entrances with 126 bronze statues of “writers, scientists, and artists past, present, and future.” Its surrounding piazza would traverse 16 city blocks. The domed buildings in the piazza’s four corners would house a technical laboratory, a scientific research laboratory, and a chemical laboratory. The last building would be administrative offices and a restaurant. In the four corners of the garden would stand four pedestals carrying four bronze statues of allegorical figures representing the four seasons. The television antenna on the actual Encyclopedic Palace would reach 407 feet into the air. 220 Doric columns lining the piazza would be reserved for more statues of future authors, artists and scientists. Marino Auriti filled notebooks with his vision for the Palace. He estimated it would cost around two-and-a-half billion dollars to build.

Marino Auriti never found a patron for his life’s work. He wrote letters to possible supporters in vain. Auriti exhibited his model twice: once in the lobby of a bank on Broad Street in Philadelphia and once in a storefront. After that it became the stuff of local legend. When Auriti died, Il Enciclopedico Palazzo del Mondo was stored in pieces in a warehouse in Delaware. His daughter became the caretaker of the pieces, and then his granddaughter. A few years ago, Auriti’s granddaughter grew tired of seeing her grandfather’s passion moldering in Delaware. Around 2003, she and her sister at last found a home for The Encyclopedic Palace model at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City, where it is today.

Il Enciclopedico Palazzo del Mondo, in its new home at the American Folk Art Museum.

Auriti’s granddaughter and the American Folk Art Museum staff were thrilled when curators of the Venice Biennale decided to make Il Enciclopedico Palazzo del Mondo the theme of this year’s festival. Massimiliano Gioni, critic and co-curator of the Biennale, explained the choice in his introduction on the Biennale website:

The dream of universal, all-embracing knowledge crops up throughout the history of art and humanity, as one that eccentrics like Auriti share with many other artists, writers, scientists, and self-proclaimed prophets who have tried — often in vain — to fashion an image of the world that will capture its infinite variety and richness.

These personal cosmologies, with their delusions of omniscience, shed light on the constant challenge of reconciling the self with the universe, the subjective with the collective, the specific with the general, the individual with the culture of her time. Today, as we grapple with a constant flood of information, such attempts to structure knowledge into all-inclusive systems seem even more necessary and even more desperate.

In his introduction, Gioni indirectly draws a connection between The Encyclopedic Palace and the Internet, two “all-inclusive systems” designed to hold universal knowledge. Indeed, if the internet could suddenly become matter — if all the information could be touched and walked around, could be seen as a collection on walls and shelves and pedestals — it might look like Marino Auriti’s dream.

It’s unsurprising that the creator of The Encyclopedic Palace of the World would be a fan of the Renaissance. Renaissance artists believed there was a special relationship between art and knowledge. These were artists who wrote aphorisms like “The painter has the Universe in his mind and hands,” and “The knowledge of all things is possible” (these are both Leonardo). For Renaissance artists, art based on feeling was mysterious and personal; art based on knowledge made art teachable and sharable.

Like Marino Auriti, Renaissance artists were classicists. The classical influence in The Encyclopedic Palace is notable. All the towers and tiers and columns and balustrades and allegorical statues and emphasis on natural light evoke a better time, a more sensible time, a more beautiful, heroic time. The Greeks and Romans prized knowledge and built palaces to hold this knowledge — the foundations of our modern libraries and universities. University, universitas — a home for the great universe of knowledge. For Marino Auriti, the decision must have been obvious: A museum of universal knowledge simply must have a classical design.

Marino Auriti standing with his model.

One can’t help noticing, however, another influence in Auriti’s design. The Encyclopedic Palace tower looks a lot like the Eiffel Tower; the surrounding piazza could be the Crystal Palace. When I first saw pictures of The Encyclopedic Palace of the World, it reminded me of the Latting Observatory, a wooden tower 315 feet high built in the mid-19th century. From the Latting Observatory you could see all the way to Queens, Staten Island, and New Jersey. Like the Eiffel Tower and Crystal Palace, the Latting Observatory was built for a World’s Fair. Specifically, the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, held in 1853 in what is now Bryant Park in New York City. The fair was a big deal in its time, even inspiring a poem from Walt Whitman. He called the poem “Song of the Exposition”:

a stately Museum shall teach you the infinite, solemn lessons of Minerals;

In another, woods, plants, Vegetation shall be illustrated — in another Animals, animal life and development.One stately house shall be the Music House;

Others for other Arts — Learning, the Sciences, shall all be here;

None shall be slighted — none but shall here be honor’d, help’d, exampled

It sounds just like the statement of purpose for Il Enciclopedico Palazzo del Mondo.

World’s Fairs once had a special significance for immigrants like Marino Auriti. These were, after all, the people that made industry go. In the Industrial Age, World’s Fairs were affirmations of The City. The tenements and alleys of Chicago and New York City and London were themselves micro-expos of international knowledge. At the World’s Fairs, they shared their customs and achievements; the sharing was democratic and beautiful. At the Fair, the nations of planet Earth all came together. At the Fair, all the fragments were made whole. As Whitman wrote:

Around a Palace,

Loftier, fairer, ampler than any yet,

Earth’s modern Wonder, History’s Seven outstripping,

High rising tier on tier, with glass and iron façades….Somewhere within the walls of all,

Shall all that forwards perfect human life be started,

Tried, taught, advanced, visibly exhibited.

Both the Latting Observatory and the Crystal Palace burned down a few years after the Fair’s end. It’s as if the buildings were so inflamed with idealism they literally burned up with it.

Nearly 20 years later, in 1871, Whitman recited “Song of the Exposition” at the opening of an industrial fair in New York City. He published the poem that same year. Its original title was “After All Not to Create Only.”

It’s not immediately clear why Marino Auriti gave his life’s work an Italian name. After all, Auriti had lived in Pennsylvania for around 30 years by the time Il Enciclopedico was completed. Born in 1891 in the town of Guardiagrele, Auriti’s Italy was one uprooted by the rise of Fascism. Auriti’s granddaughter writes of a young Auriti who published anti-Fascist poems in the local newspaper and was made to drink castor oil in the streets by “Blackshirt goon squads.” Auriti left Italy with his brother in the late 1920s. The Fascists took over their house and Auriti never quite got over the loss of his homeland. Though she was only a child when he died, Auriti’s granddaughter remembers her grandfather as sullen, a man who rarely laughed or smiled. “He didn’t seem to have a lot of use for English,” she wrote on her blog, “or America, or the late capitalist twentieth century.”

Why did Marino Auriti — an Italian-American car mechanic living in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania — dedicate the last years of his life to an impossible palace of knowledge? The Italian name might be the key.

In the period between ancient Rome and the Renaissance knowledge was, by definition, local. But the Renaissance set off a new era of global exploration. Merchants and explorers set off from Europe to distant lands. They returned home with imported knowledge — customs, folk wisdom, beliefs — and shared it with their countrymen. Local knowledge from around the world was curious, interesting, fascinating. It was stored in books and libraries, taught in schools, placed on shelves out of context, like a monkey in a zoo.

The philosopher Simone Weil would have called this the “uprooting” of knowledge.

A lot of people think that a little peasant boy of the present day who goes to primary school knows more than Pythagoras did,” she wrote in The Need For Roots, “simply because he can repeat parrotwise that the earth moves round the sun. In actual fact, he no longer looks up at the heavens. This sun about which they talk to him in class hasn’t, for him, the slightest connection with the one he can see.

For Weil, facts about the planets ought to be rooted in a boy’s experience of the sky. Facts about the planets may make the peasant boy educated. The facts may be exciting for him to learn. But unless this information is rooted in something real, Weil was saying — his community, his family, his history — the heavens become merely a wonderful and amazing storage space for trivia.

Along the lintels of Il Enciclopedico Palazzo del Mondo, Marino Auriti put a number of sayings. “Forgive the First Time.” “Do Not Abuse Generosity.” These phrases are not quotes from important scientists or artists. They are not from the Bible, not from a philosophical treatise. They aren’t general facts. They don’t have that much to do with the concept “human achievement” as it’s usually thought of. On the lintels of his Palace of universal human knowledge are things Auriti’s mother may have told him. Marino Auriti designed an Encyclopedic Palace of the World to be built in Washington, DC. He gave his project an Italian name and covered it with personal aphorisms. It’s almost as if Auriti, having lost his own place in the world, was designing a tiny universe where the very best of all human knowledge had something to do with him. Somewhere in the big history of art and achievement was a place for Marino Auriti.

“The dream of universal, all-embracing knowledge crops up throughout the history of art and humanity,” wrote Massimiliano Gioni. It’s the dream of the Internet and the Encyclopedic Palace and the Encyclopædia metropolitana and Otlet’s Cité Mondiale and Pliny’s Naturalis Historia and all universities and every World’s Fair ever. Each time the dream crops up, we will likely find ourselves asking the same questions Weil did. They are the questions Marino Auriti was asking, too. How do we take a whole world’s worth of available information and find the meaning in it? How do we keep the flood of information from drowning us? How do we keep knowledge from becoming abstract? How do we, as Gioni wrote, reconcile the self with the universe? How do we keep knowledge rooted?

Il Enciclopedico Palazzo del Mondo is therefore quite a good theme for the Venice Biennale, an international exposition in the grandest, World’s Fair style.

Long ago, before she died, Marino Auriti’s daughter had a dream about her father. “She was back at the house in Kennett,” wrote Auriti’s granddaughter, “and walked out of the kitchen door and into the side yard… My grandfather was standing there, looking like a young man, and in his hand was a tiny, living tree with its root ball intact. He looked at her and said: Io vivo.” I live.

He had finally found his roots. • 24 May 2013