I couldn’t figure out why I was having such a hard time concentrating on Daphne Gottleib’s anthology Fucking Daphne. Instead of writing her sex memoir, Gottleib asked the men and women from her past to write it for her. The result is a collection of true stories and fantasies about her sexual past, and I was bored out of my mind. There was certainly enough that should have kept me interested — Daphne fucking in a cemetery, Daphne choking a man in a San Francisco bathroom, Daphne sleeping with the girls in her writing class. Then halfway through the book, Colin Frangos used his contribution to refuse to participate. He explains:

I’m not against sex, or even sexy stories. But it pales in comparison with the excitement of discovering what it means to be alive and under your own power. And the act itself is so empty without all of the human bits around the edges — the seduction, the loneliness, the excitement. So much more interesting than sex… [U]nless you’re there and getting sticky, it’s just not an interesting subject.

The contributors to Fucking Daphne kept describing her as some sort of tattooed, bisexual superhero. “Intimidating,” “Amazon,” “perfect.” No wonder the Pulp lyric kept running through my head: “You’re just so perfect, you don’t interest me at all.” It wasn’t human enough to be relatable or hot. Writing about sex is tricky. It’s not just the what-goes-where parts (although the existence — and the number of potential nominees — for the Bad Sex in Literature Award proves that that part is not easy). The human bits — the excitement before and the morning after, the balance between the afterglow and the “My god, what have I done?” — are important to get right. If you don’t, even the most poetic and skillful description of the act itself will take the reader out of the story.

Last year, Kerry Cohen Hoffman published Easy, a young adult novel about a 14-year-old girl who tries to fill the void in her heart left by her parents’ divorce with sex. Well, one act of sex with a 20-year-old, a little fooling around, and a sort of blow job. The sex is not just unsatisfying, but deeply unpleasant. “It hurts. A lot. Enough that I feel tears come into my eyes.” Cohen compares the experience to rape, and Jessica flees to a “superhot shower” and immediately comes down with an illness that leaves her bedridden and weak. It does not appear to be a sexually transmitted disease, more like one of those hysterical Victorian illnesses.

As a cautionary tale about promiscuity, the book is a total failure. Easy is the slutty equivalent of Reefer Madness: Instead of marijuana that leads to murder, prostitution, and death, sex leads to disease, pregnancy, and social isolation. Jessica learns the error of her ways before the end of the school year and comes clean with her friend Elisabeth. Elisabeth asks, “Would you do it again?” “I consider this. ‘Only with someone I really loved. And only if I felt ready,’” Jessica answers. Cue “The More You Know” graphic. The problem is kids are smarter than that. Drugs can be fun, sex can feel nice. If you pretend like it’s always a miserable experience and are heavy-handed with the moral, the message is lost.

Losing your virginity can be traumatic. You think it’s all waves crashing on the beach and fireworks, and instead maybe it lasts 20 seconds and kind of hurts. But the real message from Easy isn’t that you should save your virginity until you’re older and in love, it’s that girls are murder. It was not the boys who judged Jessica for putting out, but her new queen bee friends. When it gets around that Jessica went into the back room at a party with a boy she wasn’t dating, the girls turn on her.

When I get back to my desk, a few kids are giggling. Ashley, in front of me, sits perfectly straight. I look down and see what’s so amusing. Ashley wrote SLUT on my notebook. Heat comes into my face. Then tears. I blink them back, refusing to let anyone see me so bothered.

There are a few scenes with the school slut, i.e. the girl who developed first. Jessica used to be her friend, but dropped her when the rumors started about how easy she was. It’s never clear if the incident that led to the rumors was a rape or not, and the issue is dropped. When Jessica cleans up her act, that’s the end of the rumors, too. That’s not really how high school works — nor, unfortunately, the world after high school — and Easy is frustrating with its perfect bow of an ending. We are in a young adult literature revival, with complex storylines and ambiguous morality. Easy feels like the kind of book your mother would like you to read.

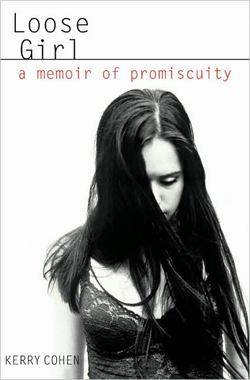

Cohen (today minus the Hoffman) was not the school slut. She slept around, but she was smart enough not to do it with anyone from her school. After Easy, she decided to revisit the subject less than a year later, this time as a memoir. Loose Girl: A Memoir of Promiscuity tells the story of the 40 or so (according to her introduction) men she slept with. The opening seemed strangely familiar. From page one of Loose Girl:

A semi truck, slowing at an intersection, honks. I look up and see a middle-aged man, thirty-five, maybe forty. He is smiling at me, his eyes on my body, dark stubble on his cheeks and chin… The man’s eyes linger on me, friendly, suggestive.

From page one of Easy:

Screeching brakes from a semi truck bring me back. I’m on one of my walks, waiting to cross the busy freeway. The driver is watching me and blasts the horn. He’s maybe thirty years old, wearing a white tank top. He has blond hair and thick stubble… My eyes lock on his and he flashes a warm, friendly grin. There is something else in his eyes too. He’s interested, admiring.

It’s not only the opening that’s the same. In both books, the mother becomes a pathetic, clinging thing after the divorce. The older sister sacrifices her social life and happiness to pick up the pieces of her mother. The father is immature, and his new girlfriend is the only person with any redeeming qualities. Both books have pregnancy scares (although only Loose Girl includes a strange recipe for a homemade abortion, which surely the editor should have excised). The endings are basically the same, too — in Easy, Jessica meets a boy from another school who doesn’t know about her reputation, and in Loose Girl, Kerry ends up married.

The moralizing is also still quite present, and the sex is just as bad — a lot of missionary position, premature ejaculation, and non-reciprocated oral sex. Cohen only mentions one position other than missionary, and she calls it demeaning. It’s not the superhero version of sex in Fucking Daphne, but it’s still lacking in a nuance that might make the book realistic. Cohen includes a fantasy about Robert Chambers, aka the “Preppie Killer,” which feels as forced as the rape metaphor in Easy. “I would have held his hand in the park, as I imagine he held Jennifer’s [his victim]. I would have allowed him to push me into the deep, damp grass, to wrestle off my clothes, to bite at my neck.” But when her friend’s boyfriend rapes her, it is never mentioned again. There are no aftershocks and no healing process. She skims over the one genuine moment of the book with no explanation.

One major problem with memoir is that inevitably you’re not just writing your story, but also the story of those around you as well. Daphne Gottleib used this idea as a basis for an interesting, if not successful, experiment. Cohen ignores these boundary issues. She makes it clear that she blames her parents inability to love her unconditionally for her sleeping around. She describes her mother as, “lost and wanting, desperate for love. She’s gone so far into her life, and yet she’s still like a child, tugging on sleeves, pushing people over, trying so very hard to get what she needs… It’s so ugly.” Even if her parents were as awful as Cohen says, you can’t help but feel sorry that their issues and faults are now in hardback form. She even calls out the “school sluts” by name — both first and last. Even if she used pseudonyms, it’s a weird moment. Loose Girl is something of an act of promiscuity itself. Both are acts of undressing by someone desperate to be seen, to be understood. • 3 July 2008