Paul Gauguin’s Polynesian paintings are beautiful, mysterious things. In the 1890s, they suggested to the French men who saw them in Paris that traveling to Tahiti might include sex with gorgeous women, and maybe even men. What a Parisian woman felt looking at these paintings, I could only guess. Did she look over her shoulder to see if she’d been caught looking too closely? How did she respond to the question, not rhetorical I think, that Gauguin asks in the title of one painting, “What! Are you jealous?” In his own writings Gauguin tends to drastically synthesize the complexity of his artistic production into self-promotional statements such as, “I am beginning to think simply, to feel only a very little hatred for my neighbor – rather, to love him.” For me, it was a visceral-aesthetic response to Gauguin’s paintings, to their uncanny erotic beauty, that drew me in and sent me on a transformative journey of my own.

A century after they were created, I encountered Gauguin’s paintings in books, in all their strange and unholy loveliness. In the sticky university library in Tallahassee, Florida, far away from the Pacific Ocean and the islands of Polynesia, I pulled books and journals from the stacks to prepare for a term paper. Kicking off my flip-flops and pushing them under the study table, I began looking through my acquisitions. I found myself in the middle of a passionate web: Gauguin’s own passion for creating beautiful things, the passion of his critics (past and present) who railed against him, and my own growing understanding that things could be at once beautiful and dangerous. The paintings vibrated with luscious, unnatural color, and I encountered my own romantic-sublime experience while looking at them; they throbbed, invited me in, made me bite my pen and shift in the grungy, uncomfortable library chair.

Looking through the books, I was confronted with libidinal energy: open legs, men and women intertwined in a pansexual, cross-kingdom orgy — with the women looking out unashamed, the men gazing with longing at phallic plant forms. Aha Oe Feii?, the Tahitian title of the jealousy painting: beautiful, golden-brown women reclining on a beach of swirling pink and red and orange sand. I had grown up near beaches, but they didn’t look like the ones in Gauguin’s paintings.

I found his manuscript Ancien Culte Mahorie, illustrated with watercolors, in which sex between tattooed men and women was represented as a holy act, their desire a powerful force. (I had just begun to acquire my own tattoos, attracted by their combination of pain and pleasure and beauty.) The locations of the paintings were ostensibly Tahiti, but their unnatural fluorescence suggested an alternate world outside the predestined, the expected.

As though by an exquisite, potentially dangerous lover, I was drawn into the uncanny erotic world of Gauguin. At the same time, I was troubled by the captions and text that surrounded the pictures in the books I was looking at. Gauguin’s critics primarily argued that he was unpleasant and probably a misogynist, and I didn’t disagree with either of these assertions, but nothing I read allowed that the paintings were beautiful. I wanted, needed, to write about their beauty, an enveloping and potent beauty that suggested to me a universe beyond my everyday life of family obligations and economic limitations. On a Saturday afternoon that was still thickly humid even in October, wearing cutoff shorts that made my thighs stick to the plastic chair and surrounded by other students who looked mostly bored, asleep, or stoned, I felt a frightening and potentially unstable, but absolute, future opening within me.

Following the travels of an enigmatic, 19th-century Frenchman had not been in my original life plan. But Gauguin’s self-fashioned model of the anti-bourgeois tortured artist/romantic hero offers one option to those of us needing to leave behind a predetermined future. I come from small towns in the Florida Panhandle, where women work together and help one another out (especially when men are absent, physically or otherwise), where church is the center of social life, where cold drinks and food are offered and always accepted, and where the conversation is often graphic and gruesome. Women birth and raise children and sometimes see them die; they care for ill relatives, including ones who had wronged them in the past. Mostly they are needed — taking off is not an option. There was strength and purpose in this world, but little possibility of escape that I could see. Instead of this, I left my Panhandle life behind and pursued the esoteric and incomprehensible subject of art history, intrigued by the possibility of reading and writing about beautiful things.

And so I followed Gauguin, and art history, to Polynesia. I spent a summer researching women’s textile production in the Kingdom of Tonga while pursing a Master’s degree. On the main and outer islands, I watched women beat bark into tapa barkcloth and, under their instruction, helped them felt together the beaten strips and paint on the designs with dye made from candlenut soot. The activity was unfamiliar, but the context was not: women gathered together in the close heat of the church hall, taking about their husbands and families, asking me when I planned to find a husband of my own. While we talked, they pieced together enormous sheets of beaten bark using chunks of boiled manioc like glue sticks, minded their children, and planned a dance to be held in the same hall the next week. One woman spent some time telling me about her husband, using the present tense, and it took me a while to realize that he was dead; but as I had come from a place where the devil appears on people’s front porches and disgruntled ghosts haunt the living, I was not troubled by this. Gauguin never went to Tonga, but the women there were beautiful and strong and possessed an inward dignity and power, like the women in his Tahitian paintings.

And so I followed Gauguin, and art history, to Polynesia. I spent a summer researching women’s textile production in the Kingdom of Tonga while pursing a Master’s degree. On the main and outer islands, I watched women beat bark into tapa barkcloth and, under their instruction, helped them felt together the beaten strips and paint on the designs with dye made from candlenut soot. The activity was unfamiliar, but the context was not: women gathered together in the close heat of the church hall, taking about their husbands and families, asking me when I planned to find a husband of my own. While we talked, they pieced together enormous sheets of beaten bark using chunks of boiled manioc like glue sticks, minded their children, and planned a dance to be held in the same hall the next week. One woman spent some time telling me about her husband, using the present tense, and it took me a while to realize that he was dead; but as I had come from a place where the devil appears on people’s front porches and disgruntled ghosts haunt the living, I was not troubled by this. Gauguin never went to Tonga, but the women there were beautiful and strong and possessed an inward dignity and power, like the women in his Tahitian paintings.

A few years later, while beginning a dissertation on Gauguin, I made a preliminary research trip to Tahiti. The endless pages I’d already read didn’t fully prepare me for the extraordinary fusion of past and present, tradition and history, that I found there from the moment I hailed down le truck, Tahiti’s public transport, outside the airport. That first morning, as the sun rose over the mountains, I saw the fantastic light, form, and color Gauguin had recorded in his landscapes: Street in Tahiti, the background of Te aa no Areois. Gauguin’s paintings were present on a few pareu sarongs at the market (the batik kind imported from Indonesia, not the locally-made tie-dyed ones that I bought for myself from the women who had made them) and in a few postcard racks, but mostly I discovered a lingering sense of the world that had influenced him: the light filtering through the breadfruit trees, the heavy mist that clung to thick green leaves, the shape of the waves, the light and clouds and mist rising off the mountains after a rain, the clear bright colors of the elaborate fish that nibbled at my toes as I waded in the lagoon.

My own sensory experience of Tahiti departed significantly from Gauguin’s. Soon after his arrival, Gauguin had written to his wife: “The night silence in Tahiti is even stranger than anything else. It can be felt; it is unbroken by even the cry of a bird. Now and then a large dry leaf falls but without even the faintest noise, rather the rustling of the wind.” I awoke, instead, to the sound of buzzing mopeds, kids heading to school, barking dogs. At the supermarket, the mahu – a man who lived as a woman – who worked there batted his long, beautiful, mascara-ed eyelashes at me while delicately weighing my avocado, exhibiting his perfect manicure. At the beach, two girls borrowed my snorkeling mask to use while collecting shellfish and showed me how to crack clams off chunks of coral with a rock and eat them with fresh lime juice. While riding the bus into town a UB40 song I had liked in junior high school blasted over the stereo, and in spite of the air conditioning, I felt sweat dripping down the back of my halter top. My skin tanned and my hair went streaky blonde. In the evenings, as I walked down the road, I was surrounded by the smell of meat grilling over charcoal because, as in Florida, it’s better to keep the heat outdoors. “Hey, you speak French pretty well,” a man with whom I was hitchhiking lied, politely but generously, as I rode with him on the long trip to the Gauguin Museum on the south side of the Island.

The exquisite beauty of Tahiti’s natural landscape that surrounded Gauguin is still there, but has been joined by Internet cafes and supermarkets, by the noni juice factory in Punaauia, and the airport in Faaa, rebuilt after it was partially burned down in 1995 during the anti-nuclear riots. The mysterious, uncanny presence that had moved Gauguin to create such incandescent beauty remained elusive to me. This was not a surprise: Gauguin’s instruction to van Gogh was that painting from the imagination was superior to painting from nature. For him, painting was an intellectual and symbolic act, rather than a representational one, and Tahiti’s influence on him had been primarily experiential. Still, I felt the need to take my journey further, to chase Gauguin’s ghost, or at least to pay it a visit. (I also felt I owed him a favor, for bringing me this far.) In the main town of Papeete, I visited the Air Tahiti office and bought a ticket for Gauguin’s last place of residence, the island of Hiva Oa in the Marquesas archipelago. He lived there, in the village of Atuona, for the last 18 months of his life and was buried there just after his death in May 1903. I would get to see his grave.

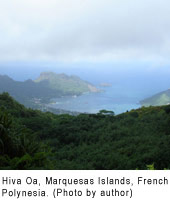

I had been told by French sailors on Tahiti and a nearby island, Raiatea, that Hiva Oa is “très sauvage,” and indeed it is. Not the residents, who mostly work in either the French administrative infrastructure or the tourist industry and enjoy watching South American telenovelas on satellite television in the evenings, or their built surroundings, which include four-wheel drive trucks, well-kept gardens, churches, and houses with lots of windows and open porches similar to those in much of the Pacific. What is savage – dangerous yet exquisite – is the landscape of Hiva Oa: deep valleys, like knife wounds in the landscape, with dense forests of fern and pine, juxtaposed with cloud-draped mountains ascending vertically from the shore. Hiva Oa lacks the white-sand beaches with a single swaying palm seen in tourist photographs from much of French Polynesia. Instead, sheer cliffs descend to just a few feet of rocky black-sand beach before the waves come in. Many coastal villages are accessible primarily by boat because roads can be impassible. The clouds and sea and frequent rain do little to dispel the thick, still heat and humidity.

I arrived on Hiva Oa in the early afternoon after a five-hour flight from Papeete. The airport was a small, well-maintained, open-air structure in the middle of the island, several miles from Atuona on the coast. As I settled myself and my small pack on a bench, waiting for my hosts to pick me up, I wondered what I’d encounter on Hiva Oa, other than Gauguin’s bones. I felt the sense of anxious expectation that often precedes an extraordinary event, such as a hurricane, or running into a former lover: We can anticipate it, but aren’t sure how we’ll respond to it until it actually happens. Soon, however, I was presented with a more immediate dilemma: my hosts had forgotten me. “Hey, you need a ride?” one of the airport workers offered, noticing me alone on my bench after the crowd of Marquesans, who had come to meet family members on the flight, had dissipated. I followed him and a coworker to his new extended-cab Toyota pickup, and climbed into the back seat. They slid a Sean Paul CD into the stereo and, as we bumped down the windy rocky road towards town, we began the standard friendly-curious conversation I’d so often had in the Islands. Was I from England? (Not that I speak with a British accent, but Americans seem to rarely travel on their own.) “Non, Californie,” I replied, where I had moved for graduate school. “You are traveling alone.” (Always in the declarative, never a question.) Yes, I replied, I’m researching Gauguin. (Gauguin always aroused only a mild curiosity.) Did I like Sean Paul? Yes, I had the same CD at home in the States.

Gauguin’s grave is located in the large Catholic cemetery on the hill above town; the cemetery figures prominently in one of his last, most atmospheric paintings, Women and a White Horse. When the airport guys dropped me at my pension, I declined their offer to meet me for a beer later. I was anxious to visit the grave, to encounter whatever it was that I would find there. That first day, as the late afternoon light refracted over the high peaks above town, I climbed the steep hill to the graveyard with two children from my pension family. Their mother, unnecessarily embarrassed by the oversight around picking me up, had told me about the cemetery as she helped me settle into my room. “Là-bas,” were the directions she’d given, as she’d smoothed a clean coverlet over the bed. The air was thick and hot and buggy, and I remembered my own mother, on August afternoons, post-thunderstorm, observing, “It’s like a wet blanket out there,” as she plugged the TV back in after the danger of lightening strikes had passed. As I followed the kids up the hill, steam rose off the pavement and the bugs buzzed loudly.

Gauguin’s grave is located in the large Catholic cemetery on the hill above town; the cemetery figures prominently in one of his last, most atmospheric paintings, Women and a White Horse. When the airport guys dropped me at my pension, I declined their offer to meet me for a beer later. I was anxious to visit the grave, to encounter whatever it was that I would find there. That first day, as the late afternoon light refracted over the high peaks above town, I climbed the steep hill to the graveyard with two children from my pension family. Their mother, unnecessarily embarrassed by the oversight around picking me up, had told me about the cemetery as she helped me settle into my room. “Là-bas,” were the directions she’d given, as she’d smoothed a clean coverlet over the bed. The air was thick and hot and buggy, and I remembered my own mother, on August afternoons, post-thunderstorm, observing, “It’s like a wet blanket out there,” as she plugged the TV back in after the danger of lightening strikes had passed. As I followed the kids up the hill, steam rose off the pavement and the bugs buzzed loudly.

Upon Gauguin’s death, his nemesis in Atuona, Bishop Martin, wrote to his superiors in France: “The only noteworthy event here has been the sudden death of a contemptible individual named Gauguin, a reputed artist but an enemy of God and everything that is decent.” Nicole and Jean-Claude led me into the cemetery, which needed to be mowed but was otherwise well-tended. And there he was, not so far from the entrance. Most of the graves, including those of the Belgian singer Jacques Brel and Bishop Martin, were covered with concrete slabs, painted white, and topped with white crosses. Gauguin’s grave was framed with local stones and topped by a modest marker. “Paul Gauguin, 1903″ had been carved into the headstone in shallow letters and painted white. There was a bronze replica of his Oviri ceramic sculpture, which he’d made in Paris and had intended for his grave. The original never made it to the Islands – it’s now in the Musée D’Orsay in Paris – and the current replica was a replacement of an earlier, stolen one; this one was bolted down. We surveyed the town and small bay in the valley below us. Nicole pointed out her school, where she was learning both Spanish and English, her family’s church, and the soccer fields. I showed her how to use my camera, and she took pictures of her brother climbing the small tree above Gauguin’s grave. I’d spent a lot of time in cemeteries, in small overgrown family plots where dead farm wives were buried next to their several dead babies, helping my mother pull weeds away from modest, worn headstones. My mother had taught me to be reverential of the dead (regardless of our feelings for them when they’d been alive), so I was careful not to step on Gauguin’s grave as we explored and photographed. After spending some time with him, we left Gauguin to visit the village, having encountered no apparitions.

I flew back to Tahiti, where I waited out the remaining days before my flight home at a surf camp on the west side of the island. I met a Breton skipper, also with several days between jobs, and we struck up the temporary easy friendship of travelers, hitchhiking into town together to visit the market (I am quite adept at choosing a ripe pineapple), cooking dinner together because we could split the ingredients and save money. We spent the last few hours before my late-night plane drinking Hinano beer from heavy, dripping bottles on the veranda. Above our heads, in the rafters, geckos caught bugs near the florescent lights and held epic battles with one another. While we talked I rolled my clothes – a few skirts, a few tank tops, a few dresses – to fit in my small pack, filling in the gaps with rolls of slide film, bikini pieces, a few pareu I’d bought for presents, my small zipper bag of miniature toiletries. I gave him what was left of my sunscreen and Campsuds. He thanked me, especially intrigued by the Campsuds, then said, “You are an enigma. You are traveling alone, and you are carrying only twelve kilos. Yet you have nail polish and makeup. How is this possible?”

The Breton sailor’s words followed me home. Eventually I wrote a dissertation and found a faculty position where I teach undergraduates and do a lot of reading and writing, much of it about Gauguin. My job has also brought me back to the South: a fraught move, after crossing continents and oceans and beaches, yet I feel at home in a way I never did in my California graduate school. I recognize the birds and know what food to put out for them, I know when the wild blackberries are ripening, and I know the world my students come from. Now, I’m sitting at my desk in my home office, listening to a satellite radio station with the same music I listened to before this journey started – the Chili Peppers, the Cure, the Clash – but I’m surrounded by stacks of books and articles and things picked up on my travels. My relationship with Gauguin remains uneasy. I find his writings particularly disquieting. The descriptions of his relationships of women can be offensive, and his primitivist assertions are weird and anachronistic: “This is nevertheless true: I am a savage.” But his paintings still give me pleasure. When I am fatigued from writing, I stop and open my books and look at them, turn pages, run my fingers over their beautiful reproduced surfaces, trace the swirls of red and pink and orange. I look, also, at the picture Nicole took of me on Gauguin’s grave: I am sticky and frizzy from the heat, but I look content, and excited, and strong, so far away from my Panhandle beginnings. • 6 August 2007