“The masses are always the other, that we do not know, and can not know,” wrote British critic Raymond Williams in the 1950s just as terms like “mass culture” and “mass entertainment” were increasingly common in Britain and America. For me the term mass evokes as much the behaviors of everyday life as the religious ritual carried out with weekly precision through much of my childhood. Indeed, mass has it origins in such gatherings of believers. But as Williams reminds us, beyond the cathedral walls the word mass can be quite slippery. “In our kind of society,” he writes, “we see these others regularly, in their myriad variations; stand, physically, beside them. They are here, and we are here with them. And that we are with them is of course the whole point. To other people, we also are masses. Masses are other people.” For Williams, this distancing intent illuminates the very problem with the word itself. If we are all part of the masses then what use is the word in shedding light on lived experiences? Who, he seems to be asking, defines what constitutes the masses? To this question he concludes: “There are in fact no masses; there are only ways of seeing people as masses.”

- Mass Observation: This is Your Photo

The Photographers’ Gallery, London.

Through September 29, 2013.

Williams’ insight is useful in exploring this curious collection of photographs and archival documents that illuminate the history of Britain’s Mass-Observation. Formed in 1937 as an experiment in social anthropology that combined art, social science, and documentary practices, Mass-Observation was the first concerted effort to research everyday lives of Britons through a decidedly radical approach that employed theories of psychology and anthropology, ideas from surrealism, and a heavy dose of socialism. Founded by anthropologist Tom Harrisson, journalist and poet Charles Madge, and the surrealist painter and filmmaker Humphrey Jennings, the group’s intent was to counter the deeply middle-class representations of British life that filled the newspapers and radio commentary and shaped the political rhetoric of the era. Their hope was to offer up a more varied understanding of British society focusing on the lives of working-class Britons in an effort to create a new social democracy.

In a letter published in the New Statesman in 1937, the group announced its intention of creating an “anthropology at home” and “a science of ourselves” and invited volunteers to help research in a range of mundane activities such as the “behavior of people at war memorials” the “shouts and gestures of motorists” and even the simple elements of bodily features such as “beards, armpits, and eyebrows.” Their appeal worked, and the group attracted a number of paid and unpaid volunteers who set about gathering evidence from interviews with people on street corners, to overheard conversation in pubs, factories, stores, and public toilets, documenting the lives of people from workspaces to dance halls and summer holidays. The press called Mass-Observation a bunch of “snoopers” and “busy-bodies.” Others called them keyhole artists, sex maniacs, sissies and society boys.

“Blackpool,” by Humphrey Spender (c. 1937) © Bolton Council, from the Collection of Bolton Library and Museum Services. Courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive, University of Sussex.

In the first part of this show, you encounter the particular uses of photography in the early work of the group. In the North West seaside city of Blackpool, volunteers documented the vacationers that crowded the city’s beaches and promenade, its Coney Island-like amusement pavilions and sidewalk attractions. Blackpool had been for decades a center for working-class holidays and amusements, and the photographs capture the place from multiple perspectives: long-view vistas of crowded beaches to the more intimate shots of street vendors and tourist ramblings. These black and white image mix journalism and artistic framing. In fact, images from this project were published in the tabloid newspaper Picture Post in January of 1939, underscoring the ways such photographs served a number of conflicting purposes. While these photographs were evidence of research into people’s behaviors, they were used to mirror back those behaviors in the newspaper articles. The line between understanding everyday life and shaping it is often a fine one.

Another project from the late 1930s was documenting the industrial town of Bolton, which Mass-Observation referred to as “Worktown” deliberating echoing the anthropological study of Muncie, Indiana conducted by Robert and Helen Lynd entitled “Middletown: A Study of Modern American Culture” published in 1929. “Worktown” was Mass-Observation’s most ambitious project before the war. Volunteers became participant observers by working in pubs and factories, moving beyond just note taking by progressing to living and working in the places they observed. This of course underscores the reality that many of the volunteers were not, in fact, working class but rather from the upper middle classes, setting out to explore realities beyond their Cambridge and Oxford educations. What the researchers brought to their studies was shaped by their ideas of work and individualism, and about the lines between public and private life. How they looked at everyday life was deeply shaped by their own place in the society. From its origins, the conundrum at the heart of anthropology is a tension between the researchers and their subjects, between recording a culture and interpreting it through individual values and beliefs. The mission of Mass-Observation held a similar paradox: Lurking behind these photographs is a researcher’s vision of what everyday life in Britain should look like.

“Crowd at Market, Bolton,” by Humphrey Spender (c. 1937) © Bolton Council, from the Collection of Bolton Library and Museum Services.

Courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive.

Photographs from “Worktown” illuminate a topography of buildings and street life, exteriors and interiors that often present lyrical moments of spectatorship. One of the young photographers who worked on this study was the artist Humphrey Spender (the brother of poet Stephen Spender) who believed “truth would be revealed only when people weren’t aware of being photographed.” His images reflect this sense of casual surveillance, catching people reading in a library or children on the street. They hold a quickness of composition, and at times a blurriness of action. Others photographs offer up studies of spaces and shapes, such as the billowing fabric of washing hung out to dry along the back streets of Ashington, the repetition of the white fabric caught in flight offering its own lyrical vision of such dreary streets. Such images capture moments when surrealism and realism mix. Spender would eventually leave Mass-Observation and become a photographer for Picture Post, further marking the murky line between the researchers and the journalists.

“Ashington – Washing in road between terraced housing,” by Humphrey Spender (c. 1937) © Bolton Council, from the Collection of Bolton Library and Museum Services. Courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive.

During World War II, Mass-Observation was put into service in gathering opinions and sentiments, and in publicizing the newly established limits on vernacular photography. In 1939, the British government passed the little known “Control of Photography” Act making it a crime to photograph soldiers and military installations, among a host of sensitive sites. Mass-Observation published and distributed leaflets explaining the law, reminding citizens to “photograph scenes, not soldiers, friends, not forces.”

What was absent in this first part of the exhibition was a sense of the group’s place in a larger historical moment of photographic realism. Looking at these photographs I kept seeing other visual echoes of Weegee’s tabloid New York, Dorothea Lange’s migrants, Walker Evan’s sharecroppers, or even Brassai’s Parisian habitués. The 1930s were a moment when the photograph became a useful tool in recording our everyday lives and serving them back to us as a kind of dream. Mass-Observation was one node on a burgeoning network of visual euphoria. Just a year before Mass-Observation was founded, Life magazine published its first issue in New York. Each issue announced on its cover “Life begins…” Two years later, Picture Post began offering its weekly subscribers in the United Kingdom a rich collection of images that mixed photojournalism with celebrity culture. In two months the publication had a circulation of nearly two million people.

“Parliamentary by-election – Children hanging around outside,” by Humphrey Spender (c. 1937-1938) © Bolton Council, from the Collection of Bolton Library and Museum Services. Courtesy of the Humphrey Spender Archive.

As John Berger has noted, between World War I and II, photography enjoyed a moment when it was “liberated from the limitations of fine art, and it had become a public medium which could be used democratically.” But he also noted this moment was brief. “The very ‘truthfulness’ of the medium,” he writes, “encouraged its deliberate use as a means of propaganda.” Mass-Observation’s survey on Exmoor Village conducted by John Hinde in 1947 presents an English countryside rich in color and simplicity that documented the everyday life of the rural England as much as if fostered and idea of rural England in the post-war era. This slipperiness between propaganda and truth-telling appeared most clearly in the early 1950s when the research of everyday life that was so vital to Mass-Observation’s efforts at creating a more democratic society in the 1930s, was absorbed into the emerging consumer culture of the post-war years and the increasing reliance on public opinion surveys and focus groups. The group disbanded, its founders left for positions in the university or in marketing agencies.

Taken from Housework and Maintenance, 1983 © The Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive Courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive. Reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London on behalf of The Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive.

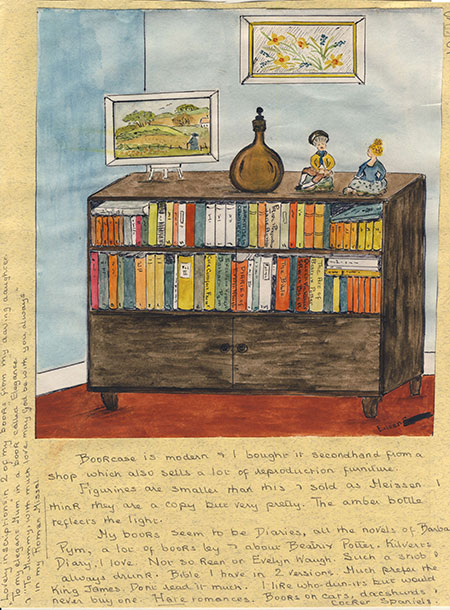

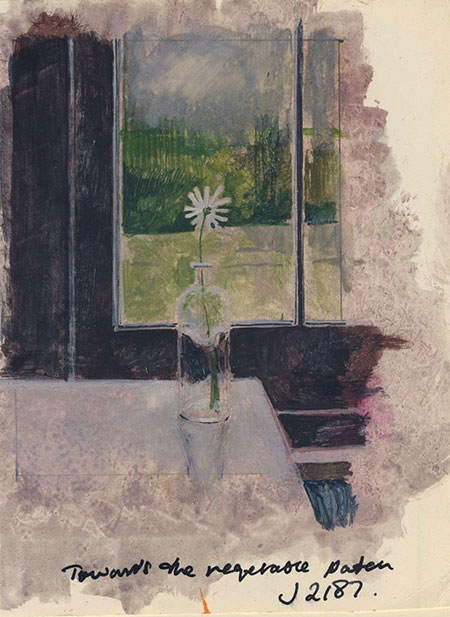

The second half of the show presents the period from the early 1980s when the group’s archive was revived for a new era that merged vernacular photography with life writing practices, turning the work of the group into an auto-ethnography that was deeply prescient as an early form of social media. The new approach presented “Directives” that asked individuals to send in a photograph around particular themes: “Housework and Maintenance” (1983), “Images of Where You Life (1995), or “Giving and Receiving Presents” (1998). Such Directives turned the “anthropology of ourselves” in an accumulation of images and stories about everyday domestic life.

Taken from Images of Where You Live, Cities, Towns, Villages, (c. 1995) © Mass Observation Archive, University of Sussex. Courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive

Displayed on the walls of the final gallery are a few samples of the thousands of materials that have been sent in for these Directives over the years, giving me the feeling that I had stepped into an unorganized archive stripped of any one narrative but rather accumulated through the minutia of individual stories and images. The intrusive “spies” of the early days are gone now, and we are left with an ever-expanding collection of self-observations, where people offer up their lives and domestic practices for visual pleasures. In the last few years, Mass-Observation’s Directives are housed on the “This is Your Photo” flickr page, which is doing a special series of Directors to coincide with this exhibition. We have all become our own keyhole artists.

And this is what the show leaves you wondering, this meta-quality of photographic practices as its own kind of living. It would be too easy to consider the ways that such auto-ethnographic practices have now become common elements in our social media experiences. Instead, what intrigued me is how hard it was to process even the small selection of images and writings presented in the second half of the show. I was left contemplating photographs and drawings, lists and writings that were deeply personal but utterly without context or meaning, the participants were nameless individuals, their photographs without labels or background. You encounter this material as a true mass of data. Experience for experience sake. What this show reminds us is how the act of taking and posting photographs has become its own form of everyday life. To rephrase Williams’ earlier comment about the masses: “there are in fact no masses; there are only ways of photographing ourselves.” • 28 August 2013