It was 500 years ago in a tiny square of the world on the Caribbean that Vasco Núñez de Balboa first heard of the “other sea”. Balboa and his fellow conquistadors had been inching their way around Hispaniola for 13 years, slaughtering, pillaging, stealing gold off the necks of local women, baptizing tribal leaders, making friends. It was a day in early 1513. Balboa’s men were resting up after successfully conquering the lands of a tribal leader they named Comagre, and whining about the amount of gold they had been allotted. Comagre’s son Panquiaco happened to be lingering nearby. It was one thing for these men to invade their land in the name of the Spanish crown, murdering and plundering as they went. But this petty display of greed was the last straw. Panquiaco jumped up in a fit of rage (or so the story goes) and knocked over the scales used to measure the gold. He then screamed at the Spanish men: “If you are so hungry for gold that you leave your lands to cause strife in those of others, I shall show you a province where you can quell this hunger.” Then Panquiaco told the Spanish of a wealthy kingdom just over the bend where everything was made of gold. The people of this kingdom were so rich, said Panquiaco, they ate off golden plates and drank from golden cups and worshipped in a temple of gold. This sounded pretty good to the conquistadors and Balboa made plans for the next expedition.

On September 1, 1513 Balboa set out along the Isthmus of Panama, the thin strip of land that links North and South Americas. He took with him around 200 Spaniards, a small brigantine, a flotilla of canoes, a handful of local guides and a pack of dogs. The party murdered their way through that isthmus until at last they reached a range of mountains that stretched along the Chucunaque River. The natives told them that, from the top of the mountains, they would see the South Sea (later known as the Pacific) on the horizon. At around 10 a.m. on the 25th of September (or possibly the 27th) in the year 1513, Balboa told his men to stand back. He wanted to ascend the mountain alone; he wanted the name Balboa to stand alone. Vasco Núñez de Balboa reached the top of the mountain by noon, and it was just like the locals said. The ocean was as boundless as it had been in his dreams. From that moment, Vasco Núñez de Balboa would be evermore known as the first European to set eyes on the Pacific Ocean from the vantage of the New World. Not even Christopher Columbus, Balboa’s adventuring mentor, could say the same. Columbus was seven years dead and it was he, Balboa, who had “discovered” the Pacific. From then on, the Atlantic and the Pacific would be connected by the power of human aspiration. It’s not exactly a true story, but no matter. Conquests are always forged in the light of myth. Without mythology human beings just wouldn’t have the stomach for domination.

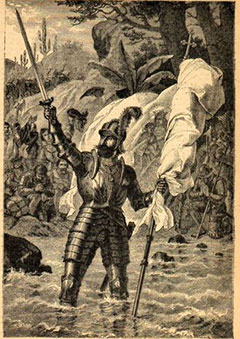

There is an anonymous 19th-century etching of Balboa standing up to his knees in Pacific waves. He wears a suit of armor and holds up his sword in defiance of geography, claiming the ocean for Spain with his eyes. He could be the Greek god Poseidon emerging from the spray, raising his trident over the quaking earth. They say that as Balboa and his surviving men stood high above the South Sea weeping with joy, the expedition’s chaplain intoned the Te Deum. The men took a tree and shaped it into a cross, surrounding it with a pyramid of stones. They carved crosses on the trees with their swords and they sang:

Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Sabaoth;

Heaven and earth are full of the Majesty of thy glory.

We believe that thou shalt come to be our Judge.

Here are a few facts about the Pacific Ocean. It is the biggest ocean by far. Four of our seven continents border the Pacific, and Antarctica would too if not for the Southern Ocean. The Pacific comprises 46% of the world’s water surface and one-third of its overall surface. This makes the Pacific Ocean bigger than all the Earth’s land area combined. The Earth is mostly water as we are mostly water, and if we think of ourselves as citizens of the world then all of us are children of the Pacific.

The moles of the new-built California towns, the endless Archipelagos, the skirts of Asiatic lands — all are washed by the same waves of the Pacific. That’s what Herman Melville wrote. “Here, millions of mixed shades and shadows, drowned dreams, somnambulisms, reveries; all that we call lives and souls, lie dreaming, dreaming, still; tossing like slumberers in their beds; the ever-rolling waves but made so by their restlessness.” The Pacific is the great Potter’s Field of four continents, wrote Melville — the Indian and the Atlantic are merely its arms. From the middle of the Pacific we could be floating in space, and human life would be just as significant. Crossing the Atlantic makes us feel important. Crossing the Pacific makes us feel anxious and small. In the peaceful Pacifico is a Ring of Fire. Beneath the Pacific lies the deepest, darkest hole in the Earth.

Europeans had been obsessed with the South Sea for a long time before Balboa. In the history books, the Atlantic is the symbol of Europe and the Pacific is the Europe-to-be. Europeans thought that by discovering the Pacific they could discover something in themselves. They got more than they bargained for, finding something “too great,” as Joseph Conrad wrote, “too mighty for common virtues,” an ocean with “no compassion, no faith, no law, no memory.”

We have become comfortable with the idea that the Age of Discovery wrought unimaginable death and violence. What seems more difficult to come to terms with is that discovery brings irretrievable loss. It’s not really a solvable dilemma. It is the nature of discovery to reveal new possibilities that result in the death of the old.

We can take comfort in the fact that it is not just a human problem. Once, the Atlantic and the Pacific held hands, connected by an ancient seaway. But far beneath the water’s surface two tectonic plates were slowly colliding. The pressure sculpted underwater volcanoes and some of the volcanoes became islands. Millions of years of tiny dances of mud filled the space between the two oceans. By the late Pliocene epoch an isthmus was formed. The formerly independent North and South America were connected by a land bridge. The seas were divorced.

For tens of millions of years, the animals of the South and North American continents had never known each other’s worlds. Now, they began to wander. Huge waves of North American bears and deer and rabbits and panthers and rats and mice and horses and camels and wolves and mastodons and saber-toothed cats walked south across the Isthmus of Panama. So did anteaters and porcupines, sloths and armadillos as big as trucks, vampire bats, and 12-foot-high terror birds caravanned north. The Isthmus of Panama became huge, unprecedented port of faunal mixing — what is now known as the Great American Interchange. Animals that had been separate for eons now met and moved freely between the continents. The two continents were forever transformed. Those animals that came from the North adapted well to South America’s tropical climate. But the animals from the South did not fare as well. Many of the species in the South had evolved in splendid isolation and were more unique than their Northern cousins. By the time they got to the colder parts of the Northern continent they began to suffer and die. In time, they became extinct. Their discovery of North America was also, unfortunately, their end. In the evolutionary story of the Great American Interchange, South America lost.

The Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa never saw Spain again. The men with whom he had traveled and slaughtered and prayed came eventually to see Balboa as a threat to their own renown. Just a few years after his glorious sighting, Balboa was arrested by a team of soldiers led by Francisco Pizarro. In January of 1519, Vasco Núñez de Balboa cried out his allegiance to Spain and then he was beheaded. Too bad Balboa could not have read Shelley. “How dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge,” said Victor Frankenstein, “and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.”

For some reason, Panamanians seem to love Balboa to this day. They feel that Balboa tried a little harder to be friends with the natives than his pirate compatriots. In Panama, Balboa is celebrated in statues and parks and avenues that all bear the name “Balboa.” There are numerous monuments that honour his “discovery” and even the Panamanian currency is called the Balboa. Carvival in Panama this year was celebrated with the country’s biggest float ever — the theme of the celebrations was “Discovery”. It is even rumored that Pope Benedict XVI will attend to pay homage to the role the Catholic Church played in Spain’s expeditions.

There will be no flowers put on Balboa’s grave, though. Nobody knows where the great Balboa’s headless body was buried, or if it was buried at all. Perhaps it was thrown to the same dogs that Balboa used to clear his path to fame. I like to think, though, he was put in the Pacific, into that great Potter’s Field of the world. • 5 September 2013