It has been a long time since Andy Warhol started being Andy Warhol. Yet we still fail to appreciate the fact that art is happening largely on his terms. For anyone who was paying attention, Andy Warhol changed the rules for art and ushered in new times. The simplest way to put it is that he made it possible — with the soup cans and the Brillo boxes and the silkscreens of famous movie stars — to make art from the world of consumer goods, the world that we’ve all actually been living in for a few generations now. Some people still don’t want to forgive him for that. But, in the end, all he was doing was telling the truth. His best work is great because of how deeply Warhol was willing to accept that we live in the world that we do. The degree to which he allowed himself to accept this world made him weird, often creepy, and entirely fascinating. He made a kind of freakish experiment with himself, to become so utterly “what we are” that he was more like us than any of us could actually be. That made him uncanny and it is why his art is about truth, even as it glories in the purity of surface and appearance.

There are two artists who best represent the legacy of Andy Warhol and have best exploited the possibilities opened up by what he was doing. One is Jeff Koons. The other is Damien Hirst. People love to despise Koons and Hirst just as much as they loved to despise Warhol. And like Warhol, the two keep making work that asks to be despised. They haven’t any other choice. That is the task before them.

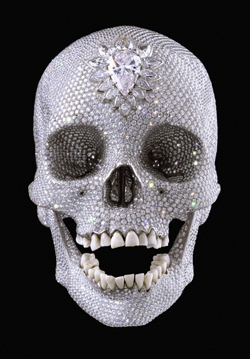

Damien Hirst’s latest outrage against the sanctity of art and the dignity of human beings is his diamond-encrusted skull. It was designed to be the most expensive work of contemporary art in the world, and it just sold for $100 million. Like everything Hirst does, the piece doesn’t shy away from what it is. It revels in it. It is meant to be expensive and it is meant to be a piece of art that is also about the fact that it is the most expensive work of art. And it is that little wink and nudge about its own expensiveness, contained within the very concept of the piece, that is so annoying, even downright intolerable to many, if not most, right-thinking people.

And yet it does so happen that there is also something else happening with the skull. The skull is a skull, and by being so it brings death into the picture. As everyone knows, Hirst has a thing about death. Indeed, most of Hirst’s work is about death, directly or indirectly. The death of the body and organic matter, disease, violence, decay. He’s interested in death and he knows that we are, too. It is also obvious that the skull immediately brings to mind the memento mori, a reminder of death. Western art is filled with them. And generally the memento mori is meant to serve as a wakeup call. “Don’t forget that you’re going to die,” and more importantly, “Don’t forget that you’ll more than likely burn in hell for eternity.” The purpose is thus to redirect attention away from earthly things and back toward concerns of the soul.

The interesting thing about Hirst’s memento mori is that it doesn’t really do that at all. It does the opposite. Encrusted with diamonds, the skull seems to say, “Since we’re all going to die, the only things we really have are earthly things, so let us worship them in our ways.” This is, in fact, a much more classical way to view the memento mori. It is in line with the Roman fatalism that says, “Let’s have a drink and a screw while we can because we’ll all be dead soon.” Carpe diem.

So, in a way, Hirst’s skull completely upends the whole point and purpose of the memento mori in the largely Christian tradition of the last thousand years. And its being outrageously expensive allows it to do that. If he simply presented a skull or sculpted a skull it wouldn’t have that kick that undermines the traditional sense of the memento mori. At $100 million the skull doesn’t point to anything transcendent anymore. It doesn’t point to the soul or to matters of the afterlife. It is so lousy with diamonds that it has lost all capacity to be elevated. And to add insult to injury, Hirst titles it “For the Love of God.” You can see the bite of the pun if you add an “Oh,” as in “Oh for the Love of God.”

•

In the early 1960s Warhol started working on his Death and Disaster series. One of the works in the series is called Green Car Crash (which actually sold at auction in May for more than $70 million). It is the reproduction of a photo of a car crash in suburban Seattle. A totaled car burns in the street while the driver is in his final death throes, impaled on a pole nearby. Disconcertingly, a passerby strolls along the sidewalk in the background, seemingly unaffected by the sight. It is a disturbing work, primarily because it says nothing about death at all. Death is just death. It is meaningless and horrible at the same time. It’s a kind of mundane mystery. An individual human life is always teetering between that mundanity and that mystery. Forced to live under the eye of an immanent death that leads nowhere, we spend most of the time trying to forget about the weirdness of it all, punctuated by flashes of panicky self-awareness about where it all leads. Death, in short, is a deeply fucked-up thing.

Hirst’s obsession with death is in direct lineage with Warhol’s Death and Disaster series and is as concerned with sweeping away the metaphor and symbolism around death in order to confront again the essential weirdness. His most iconic work, the shark in the formaldehyde, is called The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. That Hirst would do a reversal on the memento mori is therefore unsurprising. That it would annoy and shock and glimmer and shine is all the more fitting. As Horace would say, “Nunc est bibendum, nunc pede libero pulsanda tellus.” “Now is for drinking, now is for kicking up the heels a bit.” • 11 September 2007