There’s a place in France where the naked ladies dance. There’s a hole

in the wall where the men can see it all. Except in this case, the lady

isn’t dancing. She’s lying naked in a park. Her legs are splayed open

to reveal a hairless vagina, more of a cleft than anything else. A

waterfall glitters in the background. She could be a corpse but for the

fact that she is holding a lantern with her left arm. From the peephole

in the wooden door we cannot see her head.

- “Marcel Duchamp: ‘Étant donnés'” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Through Nov. 29, 2009.

This is Marcel Duchamp’s last work. It is three-dimensional, something like a diorama. The naked woman is a life-sized model made from a cast of a woman Duchamp was once in love with. The scene is “realistic,” if in a wax-museum sort of way. The fact that you view it through a peephole in a door makes it all seem rather naughty. Early reviewers of the work described it as a scene of “sexual invitation, sadism, rape, death.” It has always made people uncomfortable. Duchamp produced it in secret over 20 years, having told the world that he had given up art for chess. Called “Étant donnés,” it can be found at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, home of the largest collection of Duchamp’s work.

|

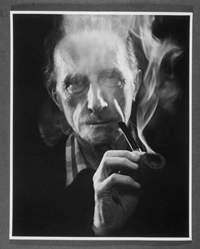

| Marcel Duchamp (With Pipe), 1957. Philadelphia Museum of Art. |

Marcel Duchamp had a long history of making people uncomfortable. He is best known for a urinal, signed R. Mutt, that he displayed as a work of art for an exhibit by the Society of Independent Artists in 1917. The urinal was selected as the most important artwork of the 20th century by a panel of important persons a few years ago. At the time, Duchamp was asked to remove it. He quit the Society instead.

But Duchamp’s first real impact on the world of art was with a painting — specifically, a nude. It was called “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.” She isn’t much to look at. All shapes and lines and movement, she is the abstracted idea of a nude descending a staircase. It upset people. The aggressive abstraction of the painting mixed with the reference to nudity in the title pissed people off.

His next important work, “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass),” seems erotic in its idea and in its title. Composed of two large glass panels, the top is the domain of the bride, the bottom the domain of the bachelors. There’s supposed to be a relationship of desire between the two halves of the glass. The female bride is unattainable in her section, the bachelors lurk around in frustration below. But if this is a piece of erotic art it is heavy on the mystery and light on the screwing.

At other times, Duchamp could be more explicit. He once ejaculated onto a framed piece of black satin and called it “Paysage fautif” (Faulty Landscape). But none of Duchamp’s previous works are quite like “Étant donnés.” It is a work charged with erotic energy, though it is very difficult to explain exactly how, or why.

This raises a question: What is erotic art? What makes it erotic? “Étant donnés” features a naked woman, but so do thousands of works throughout the history of art, many of which have little to do with eroticism. Nakedness alone is not enough. The crucial factor, then, could be sex itself — the suggestion of sex, the aura of sex, its actual depiction. Plenty of art that we readily consider erotic is, by definition, related to sex. Problem is, it doesn’t have to be. There is something more intangible that tugs at the edge of the erotic. Maybe it’s just the presence of desire. Maybe it’s a kind of unease.

|

|

“The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass),” 1915-23.

|

It is hard to say what “Étant donnés” actually depicts. Jasper Johns called it “the strangest work of art any museum has ever had in it.” The full title of the work isn’t much help: “Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas…” If we can call the work erotic it surely has to do with the manner in which it is viewed. It is the peephole that sets the scene. When you walk into the room where “Étant donnés” is housed, all you see is a wooden door on the opposite wall. You have to walk up to the door and examine it. That’s when you notice the two little holes at roughly eye level. When you look through the holes you see the scene in the park, the naked woman, etc. It is impossible to “look around.” The placement of the holes prevents this. You will never see the face of the woman in the grass. You will never understand anything more about her situation than what you see through those little holes.

There is an overall feeling that maybe you are looking at something you shouldn’t be looking at. The intimacy of your peeping certainly contrasts with most experiences you’re going to have at a museum. It’s just you, and the exposed vagina, and the absurd waterfall twinkling in the background.

Georges Bataille (a French theorist who wrote a book called Erotism) argued that what we call “erotic” comes from the transition from unashamed sexuality to sexuality with shame. Erotic feelings, then, have their source back in the murk of prehistorical beginnings, in the changes that came about in the transformation from animal to man. Bataille thus connects erotism deeply to religion. That’s not as paradoxical as it seems. In religion, we have the root impulse for human beings to regulate themselves, to set up taboos and rituals that disentangle the shameful and the unshameful. Religion is possible only in a self-conscious kind of creature, a creature that doesn’t just do, but reflects on the doing. Most animals simply perform the sex act. Human beings have to think about it, wonder about it, and ultimately decide under what conditions it is good or bad.

Bataille sees the essence of the erotic in this disequilibrium, the sense of doubt that is made possible by that self-awareness. Human beings have urges that they do not trust and seek to repress. That, says Bataille (and your therapist) is a big deal. At the same time, we’re drawn to spaces and situations where taboos can be suspended. We want to experiment with our doubts. The taboo is fully real when we’ve poked at its boundaries, tested its limits. And that is a personal thing, a private thing. Taboos, rituals, rules — these are public things. Taboos are enforced by the group. Rules and regulations are the very stuff of societies and institutions. Transgressing a taboo, though, is a subjective affair. Bataille says, “The inner experience of eroticism demands from the subject a sensitiveness to the anguish at the heart of the taboo no less great than the desire which leads him to infringe it.”

The creepy feeling that comes with viewing “Étant donnés” is in the privacy of it, the way that each viewer has his or her own experience of wanting to look and being troubled in the looking. When you step up to the door everything else goes away. It’s just you and that vagina in the grass (“my woman with the open pussy” as Duchamp once referred to her). And speaking of grass, damn if that park doesn’t seem a lot like a grotto. Secret things happen in grottos, intimate things, primal things. Early humans went into grottos and caves to do magic and worship fleshy figurines. The grotto is a place where that transition from animal to human still feels fresh. It’s a place both comforting and scary.

And it’s not just the grotto and the peephole. There’s secrecy in every part of the work. Duchamp hid “Étant donnés” away for 20 years. Friends visited Duchamp in his studio apartment, never realizing that his final work was slowly coming into being in the next room. Duchamp talked of the need to work “underground,” of the fact that art happens best in secrecy.

Here’s Bataille again: “My starting point is that eroticism is a solitary activity. At the least it is a matter difficult to discuss. For not only conventional reasons, eroticism is defined by secrecy. It cannot be public. I might instant some exceptions but somehow eroticism is outside ordinary life.”

The real genius of “Étant donnés,” then, is to have brought the intensely solitary, secretive nature of eroticism into a work of art that is inherently public. Plopped down into ordinary life, it transports you out of the ordinary right away. “Étant donnés” is not “about” eroticism, nor is it erotic in the same way as a page from the Kama Sutra. Étant donnés is erotic because it makes you feel the disequilibrium that Bataille talked about. It actually creates an inner experience of mingled shame and desire. It takes you back to the Garden, the primal Paradise, where we looked upon ourselves and suddenly knew shame at our own nakedness. In the end, the great innovator, Mr. Modernity himself, Marcel Duchamp, went all the way back to the beginning. • 6 October 2009