Toward the end of every summer, I start telling myself that this will be the year I’m finally taking that trip to view fall foliage. The prospect of an autumnal jaunt is really about getting through the despondence of that season’s end, I think, because I never do make such a trip, and I honestly don’t even know what it would mean to go on a fall foliage trip. Do you stick to roads? Hike? New England sounds nice, but that’s awfully general. How much time should one allot for looking at changing leaves? Would three days fly by, or would an hour feel like a lifetime?

Not everyone sees fall as so gloomy, or fall foliage viewing as so formless an activity — state tourism and environmental agencies, for instance. Where you see red and orange and yellow, they see green, and they’re all scrambling to grab as much as they can from what are affectionately known in New England as leaf peepers. It sounds like a pretty dog-eat-dog industry. In the Journal of Vacation Marketing, Black Hills State University business professors Daniel M. Spencer and Donald F. Holeck write, “Fall color tourists constitute a niche market like bird watchers, rock climbers, and a host of other groups that can be successfully exploited by meeting the needs and wants of niche members more effectively than one’s competitors.”

Exploited? Leaf peepers? Such is the ability of industry jargon to sap the romance out of anything; Spencer and Holeck, for example, describe fall color tourism (or FCT, as they call it) as “a passive pursuit that requires no skill or physical prowess,” and they mean this as a good thing! But since FCT is a small pie — their research survey found a participation rate of just 0.3 percent — competition is keen. Based on this work, the professors recommend marketers do three things: target older people, target people living nearby, and for heaven’s sake advertise other activities as well — changing colors are nice and all, but it turns out people won’t travel for leaves alone.

The information is useful to the states with large stands of deciduous trees that turn bold colors, of which there are many. Connecticut, Rhode Island, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Vermont, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, Michigan, Wisconsin, Tennessee, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Colorado all manage fall foliage Web sites. The U.S. Forest Service maintains pages for many forests and regions, as well. Depending on the agency behind them, these pages fall into one of two general categories. This first is maintained by an agency related to the environment, like Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources. This page is typically a just-the-facts, text-heavy site because, really, what did you expect from the Department of Natural Resources? Leave the responsibility to a more dollars and cents kind of agency, like New York’s Department of Economic Development, and you get a slick site with driving tours and lodging information and wool festival details and historic home listings.

The key to any fall foliage campaign is a constant monitoring of just how many trees have transformed colors; this changes yearly based on environmental factors such as rainfall and temperature. What’s the point in seeing just a few orange leaves, the message seems to be, when you can time things just right and peep them all — a moment that’s known in the biz as “peak”?

Some states share this information through telephone hotlines, like 1-800-VERMONT: “To hear the current fall foliage report, please press 1” (1!). Do this and a woman recommends highways that pass through the areas with the best color at that moment. The woman who records the Forest Service’s line is quiet and slow, but in a good, fall kind of way: “To hear predictions about leaf color, foliage peaks, scenic drives, and other fall activities, select the different Regions across the United States for information updates…” If I’m interested in touring my home state of Pennsylvania, I can download a PDF prepared by the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Forestry, which this week includes more than two pages of text and ends with a small photo of some reddish trees alongside a shady road — a scene most definitely not peak.

|

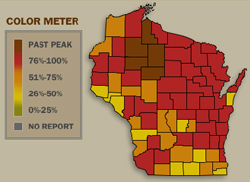

| Mapping autumn in Wisconsin. |

|

| And in Ohio. |

Of course the most popular and effective means of charting color change is though a fall foliage map. This can take many forms. Wisconsin offers a county-by-county assessment, one county seeming to enjoying full color while things remain spotty just next door. The Flash map is updated around the clock based on information submitted by leaf watchers across the state. Maine breaks itself up into seven zones. Ohio has built an interactive map covered in leaf icons; click one and you get a place name and its current color status. Most maps, however, depict color change across a state or region is a gradiational process, one that isn’t delineated by county lines or state park borders or any other division unknown to oaks and maples.

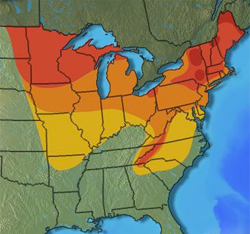

For my armchair fall foliage viewing money, I like the Weather Channel’s map best. The station maintains an entire fall foliage online portal with user-submitted foliage photos (“Autumn Pets: Fall pics, only cuter”) and links to foliage news (“Foliage smackdown: Eastern reds vs. Western goldsand”) and information on the science behind foliage change (chlorophyll breaks down). Its maps — available on the Web and presented throughout the day on television — are the same the Channel uses in its regular weather forecasts: divided along state lines, bisected by highways. They use a five-color scale. A kind of green/gray indicates little or no change. Then the colors seem to build, from a muted yellow to a light orange to a neon red. This, at last, is peak, in which 75 to 100 percent of leaves have changed. At peak, “Most trees are in full color. Deep reds and bright yellows prevail. Very little green vegetation remains. A few trees have yet to reach peak, but are showing very bright, well developed colors.” One could argue with the Weather Channel and say that the trees have been in full color since their leaves peaked out from their winter respite, but we know what they mean. The point here is that the green we celebrated since spring is no longer the star. Very little of it remains!

Alas, peak is fleeting. In its wake comes past peak: “Brightness and depth of color have begun to fade. Leaf drop has begun and will accelerate from this point.” Past peak is indicated by a that’s-all-she-wrote, see-you-in-the-spring burgundy that slowly creeps down from Canada and spreads out across the country. This shouldn’t come as a shock, I suppose. What does is how this depiction creates a sense of pressure one doesn’t normally encounter when thinking about leisure time spent outdoors. Looking at the landscape, our eyes are drawn to the trees that make peak such an appealing moment. Looking at these maps, we also see that peak is here, but we simultaneously notice that past peak is following close behind.

There is, of course, a melancholy to the sight of changing foliage. We know the transformation reveals the trees’ hunkering down for a long winter. We face those same cold, dark months. The fall foliage map charts this somber process, but it has a melancholy all its own. Looking at foliage, you’re watching summer disappear. Looking at the maps, you’re watching the same thing happen to fall.

• 16 October 2009