In the autumn of 1859, American journalist and businessman Francis Hall wandered the shops of Yokohama, Japan. Hall had just arrived in the city, five years after Commodore Perry forced a trade treaty on the country, opening ports to American ships under threat of naval attack, and ending a centuries-long isolation of Japan to most foreigners. In his journal, Hall recorded an encounter in one shop where the owner and his wife pulled out a number of boxes that contained carefully wrapped books “full of vile pictures executed in the best style of Japanese art.” He continued:

[The shop owner] opened the books at the pictures, and the wife sat down with us and began to ‘tell me’ what beautiful books they were. This was done apparently without a thought of anything low or degrading commensurate with the transaction. I presume I was the only one whose modesty could have been possibly shocked. This is a fair sample of the blunted sense and degraded position of the Japanese as to ordinary decencies of life. These books abound and are shamelessly exhibited.

A few days later, Hall reported a similar encounter at a home of a Japanese couple. He noted the wife’s immaculate and well kept home, and then described how the husband retrieved several items from a cabinet drawer. Hall wrote:

He placed in my hands three or four very obscene pictures. His wife stood close by and it was apparent from the demeanor of both that there was not a shadow of suspicion in their minds of the immodesty of the act or of the pictures themselves. They had shown them as something really very choice and worth looking at and preserved them with great care.

His shock at such “vile” pictures had as much to do with their content as with the casual display of them and what this behavior suggested about the personal habits of the Japanese. Much to Hall’s dismay, both husband and wife found these erotic images “worth looking at.”

- “Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art.” The British Museum, London. Through January 5, 2014.

What Hall’s hosts were showing him were shunga pictures, a centuries-old erotic art that is now on display at the British Museum. This expansive exhibition puts us in front of over 170 works including paintings, scrolls, and hand painted books, many of which present highly stylized scenes of sexual encounters amidst lush landscapes or richly layered interiors. The show details the historical evolution of shunga, presenting a linear timeline from early works, to the art’s most prolific era during the Edo period between 1600-1860, and the final censoring of these works in the early 20th century just as Japan was becoming more open to the West.

While today we wouldn’t claim these images are “vile” the show comes with a number of parental warnings, and the reviews have cautioned patrons that this show may not be the best place for a Sunday outing with grandma, or to take a first date. Even the press images for the show carefully crop out those explicit sexual parts of the images. Such responses to these works play on a consistent paradox in our encounters with erotic art in the West where looking and not looking go hand in hand, each titillating us in different ways even as they are circumscribed by religious beliefs.

The introductory text panel of the show tells us that these images “challenge us to reconsider the mutually exclusive categories of ‘art’ versus ‘pornography’ that evolved in the West.” But it is difficult to untangle these works from these distinctions that are themselves products of the 19th century when shunga first made its appearances in Europe and America. (As part of the treaty agreement, Commodore Perry was given several erotic pictures, a diplomatic gesture that so often gets ignored in the story of Perry’s Asian successes.) Aside from the rich aesthetic and cultural history this show presents, I was equally compelled by how our not looking at shunga has it own history.

Entering through the exhibition glass doors, you can’t help the feeling that there is something uneasy about looking at these works in such a public way, standing next to strangers gazing at paintings and woodblock prints of oversized penises and detailed vaginas, all arranged in glass cases like specimens of natural history. Or, as in other parts of the British Museum, the works sit like artifacts of a dead culture, the glass cases fostering both our curiosity as well as our distance.

One case in particular sits at table height, making its viewing accessible only to those tall enough to look down upon it. Inside there is a print displaying willow thin men arranged in a circle, each balancing his grotesquely oversized penis on a wooden stand while a representative of the court measures them. The humor of this work echoes similar grotesque and politically charged cartoons of -century France. A Japanese commentator some decades later complained about the size of “the thing” in such prints, adding “if it were depicted the actual size there would be nothing of interest.” For that reason don’t we say, “Art is fantasy?” Throughout this show, these works constantly remind us that realism is not a concern for these artists. Rather these stylized images take us beyond the everyday.

It was in the 18th century that shunga flourished amidst the “floating world” (ukiyo) school, which included poetry and paintings of the “pleasure districts” of Edo (modern-day Tokyo), where licensed brothels, Kabuki theaters, and teahouses, provided sanctioned spaces for indulgences outside the demands of the public life. Thousands of such works were produced between the 18th and early 19th centuries, for both the upper classes and the newly expanding middle class, often given as gifts for newlyweds.

Despite what these works might suggest, Japan was hardly a paradise of free love. It was instead a highly structured society organized by rules of Confucian philosophy that governed public life with a concern for duty and self-restraint. But in the private worlds, such demands were less severe. To think of shunga as purely expressive of sexual pleasure misses the meanings such works had in shaping private realities and fantasies within the Edo era. Details of houses and tearooms, flowing with ornate fabrics and objects, center many of these works. In some of the earlier prints, there is often a voyeur figure looking on through a window, wishing to join in or to watch from a distance. Interior and exterior, windows and doors, all play characters in these works, as sexual acts are deeply tied to richly rendered private spaces.

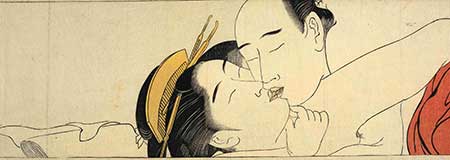

Torii Kiyonaga (1752 – 1815), detail from Sode no maki (Handscroll for the Sleeve), c. 1785.

What strikes you in these works is how much they lack a concern for the body. Consider Torii Kiyonaga’s “Album for Spring and Autumn” (c. 1708-13) a series of 12 prints that are strikingly simple in form, each composed of continuous curving lines that create a flow of bodies and clothing against a flat background. Such use of lines are seen again in his “Hand Scroll for the Sleeve” (c. 1785), presenting several horizontal format drawings depicting lovers in a number of couplings — adolescents distracted from calligraphy practice, an older couple in repose, a young courtly couple. Each couple expands along the horizontal plane as if they were seemingly squeezed within the frame of the narrow scrolls, creating a compelling intimacy and perspective.

Throughout these works, bodies are minimally rendered with undulating lines and a flat, paleness of flesh. Instead, it is the fabric that attracts the attentions, the flows of color and details of patterns that dominate many of these works, often done with vibrant colors or golden paints. It is the actions and gestures that matter, the settings and stories that the images tell. The nakedness of the bodies — what was so concerning to Western viewers at that time — was just another form of dress. The erotic qualities emerged not from the flesh, but from what is hidden and what the artists let us see. Like a striptease, the pleasures of looking are wrapped up in the flow of fabric and flesh.

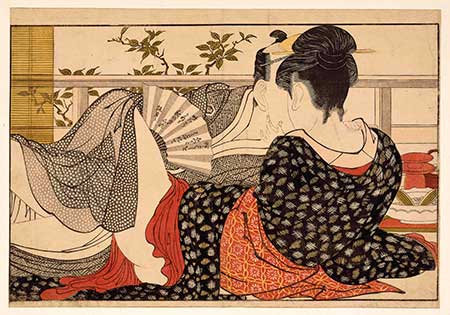

Consider Kitagawa Utamaro’s “Lovers Upstairs Room in Tea House” (c. 1806). One of the masters of the art, Utamaro presents a couple, their faces unseen, leaving us to gaze at the postures and the flow of fabric, the details and patterns rendered with precision and richness. There is also his series of prints capturing and organizing the different facial features of woman he noticed in the pleasure districts. But what strikes you throughout these works is how women’s bodies rarely become objects in themselves. Instead they pose with their partners, playful and active and often looking like equals in a sexual competition. You won’t find a single odalisque in the entire show, no voyeuristic encounter with the singularity of the female form.

Kitagawa Utamaro (d. 1806), Lovers in the upstairs room of a teahouse, from Utamakura (Poem of the Pillow), c. 1788.

Consider Katsushika Hokusai, most famous for his series of wave paintings that have become iconic of Japanese art of the 19th century. Hokusai’s works are often seen as major influence on trends in 19th century France, influencing the works of Gauguin, Toulouse Lautrec, and Degas among others. But Hokusai also produced nearly 20 shunga books and a number of large woodblock prints. His series “Adonis Flower” (c. 1822-3) captures closely pictured scenes of couples entangled in on another, the flow of bodily outlines contrasting with the undulating fabrics and flow of curtains and screens. Unlike his waves paintings with their expansive perspective, these works are tendered with concentrated intimacy, and, like Kiyonaga’s horizontal scrolls, present the couples movements, their contorted bodies, crammed into the confining space of Hokusai’s frame.

Edmond de Goncourt, the French writer and diarist, produced studies of both Hokusai and Utamaro in the mid-19th century. Of the latter work, Goncourt was effusive about the sexual energy of the works, “the furious, almost angry copulations” he called them, with their “the swooning woman, head thrown back and touching the floor, with the petite mort on her face, eyes closed under painted lids.” Much like many of his contemporaries, Goncourt brings a particular European appreciation for these works, turning the women’s bodies, reclined and receptive, into the sole object of our voyeuristic gaze.

Just as these works were finding new viewers in Europe, they were become less and less produced in Japan. As you move through this show, through the history of shunga, the images of shunga disappear. We are told that as “contact with foreigners increased rapidly in the 1860s and 1870s, stricter regulations against shunga” were enacted in Japan. The more Japan opened its culture to the West, the more it wished to be a global actor in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the more this art became an embarrassing relic of the past.

But just as Japan was suppressing shunga, new laws in the United States and England prohibited obscene forms of art and literature. In England the “Obscene Publication Act” of 1857 was meant to protect the corruption of youth, and in the US the Comstock Act of 1870 prohibited the circulation of “obscene” materials in the mail. The laws were symptoms of a new language to describe a range of sexual materials including those encountered in foreign lands of the expanding empires or the ancient artifacts of Rome and Greece. Central to this language was the word “pornography,” which was born in the 19th century as a way of defining all kinds art, creating a new class of works that were exciting by their very nature of being prohibited.

Some of the final works you encounter in this show are drawings and phallic sex toys from the collection of George Witt, a 19th century British doctor and later banker who amassed a large collection of contemporary and ancient erotic art. He left his entire collection to the British Museum in 1865, where the trustees placed it in its newly established “Secretum” or secret museum in the museum’s vaults. Stowed away with Witt’s collection were other sexual artifacts the museum acquired in the years to come and where its shunga art was hidden for decades, out of sight except for those well-educated men from Oxford and Cambridge who could handle such material.

A year before the Comstock Act, and about the same time as Hall was wandering the shops of Yokohama, American art critic James Jackson Jarve, writing in Art Journal, decried shunga as “inconceivably monstrous, betraying a liking for the absolute vices as no European nation would outwardly tolerate in any condition of society.” Such criticism, like others of the era, liked these works to the moral flaws of the Japanese. The aesthetics became a symptom of the nation.

The history of looking and not looking at shunga is deeply intertwined with our fantasies and fears about boundaries, those undulating lines between West and the East, between pornography and art. In his journal in 1863, Goncourt described his excitement with some new albums of “Japanese obscenities” he recently purchased: “They delight me, amuse me, and charm my eyes. I look on them as being beyond obscenity, which is there, yet seems not be there, and which I do not see, so completely does it disappear into fantasy.” • 4 November 2013