Gayness was invented in America. That’s the thought that slowly formed in my mind while perusing the show “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture” at the National Portrait Gallery in D.C. I’m not saying that America invented homosexuality, of course. That goes a little further back. What America did was to give gayness its specific difference, to make “gay” into an identity you could have publicly like any other.

- “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture” Through February 13, 2011. National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

“Hide/Seek” begins its American story, as is appropriate, with Walt Whitman. Walt was, after all, the great bard of American self-invention. If there was a new identity to be tried, Walt was ready to sing its praises. It has been speculated that Whitman had a more than passing interest in homosexuality. The manuscript version of his poem “Once I Pass’d Through A Populous City” contains the following lines:

Day by day and night by night we were together — all else has long been forgotten by me,

I remember I saw only that man who passionately clung to me,

Again we wander, we love, we separate again,

Again he holds me by the hand, I must not go,

I see him close beside me with silent lips sad and tremulous.

It is never clear in Whitman exactly how much he is attracted to men as men, and how much he is simply attracted to everyone and everything. Whitman’s sexuality is so overflowing as to be beyond any specific identity. One gets the feeling that Whitman got the same amount of erotic charge rubbing up against things in his kitchen as he did getting close to human beings. That is part of his overall metaphysics of joy and abundance.

Up through the early part of the 20th century, the Whitman approach to sexuality provided something of a safe haven for homosexuality. When everyone is being natural and happy and naïve, there is less need to ask specific questions. A painting in the show, “River Front No. 1” by George Wesley Bellows (1915), captures this attitude well. A bunch of guys are hanging out on the riverfront. There are all kinds of guys. Some of them have their clothes off, some don’t. There is a vague hedonism to the scene, but it is hard to place. It is not a gay scene exactly, or is it?

But it was this Whitmanesque fluidity and openness that had to be abandoned for a truly specific gay identity to emerge. Questions had to asked, identities had to be sorted out. There was a feeling, even maybe among gays themselves, that the ambiguity of the Whitman approach still glossed over a lie. A grand polymorphous panamorism might be nice as a poetic fantasy, but it did not address the problems faced by those who found themselves attracted to and falling in love with members of their own sex.

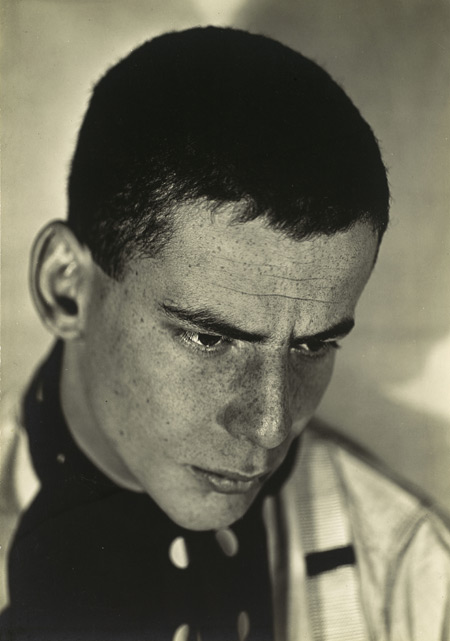

The Whitman ambiguity, however, lingered on into the period between the two World Wars. A 1930 photo of Lincoln Kirstein by Walker Evans for example, is a beautiful shot of a brooding young man. Is it also about being gay? We are not sure. The participants aren’t sure. There is no category, yet, through which that specific identity can find its voice.

The birth of that category happens, from the perspective of “Hide/Seek,” essentially with one man. That man is Frank O’Hara. I never would have thought that the problem of gayness in America could boil down to something so simple, that it could be, simply, Frank O’Hara. But Frank O’Hara stood before us as a gay man in a way that no one before him had. One painting in the show, by Alice Neel, is nothing more than Frank O’Hara’s profile as he sits alone at a table in a baggy sweater in front of some lilacs. His nose is extraordinary and rather beakish. Alice Neel called it “falconlike.” You sense, looking at the painting, that this is a man who knew who he was.

Something in the straightforward nonchalance of Frank O’Hara says that he is willing to be gay in the same way that another man is willing to be a Democrat, or an Episcopalian. He isn’t putting on a show. He isn’t masking himself in layers of false identity. He isn’t engaged in the game of hide and seek any more than he has to be. He just wants to be Frank, a human being who happens to love men.

Another painting in the show, “Frank O’Hara Nude with Boots” by Larry Rivers, says roughly the same thing, if with a little more attitude. In this painting, Frank is to be found staring out at us with his head cocked slightly to the side, naked, wearing boots. His penis hangs like a warning, neither explicitly erotic nor willing to be ignored. Frank’s penis is telling us, none to subtly, that he, Frank O’Hara, is a man, and that his maleness is an ineradicable function of who he is. Frank is not going to be pushed out of his gender by the fact of being gay. He is a man like any other, and at the very same time he is a man who happens to be gay. Come to think of it, I don’t know of any other human being who could have made that point so forcefully, just by being who they were.

The Frank who would stand naked with boots in front of you was the very same Frank O’Hara who wrote all that poetry. It was the same man who could dash off the final lines of “Les Luths”:

what are lutes they make ugly twangs and rest on knees in cafés

I want to hear only your light voice running on about Florida

as we pass the changing traffic light and buy grapes for wherever

we will end up praising the mattressless sleigh-bed and the

Mexican egg and the clock that will not make me know

how to leave you

Frank’s poetry is gay poetry, sure. It is poetry by a gay poet who knows that he is gay and doesn’t care that you know it either. But in its breezy affirmation of that gayness, his poetry immediately grabs back the universality that it might have lost otherwise. That is the great tightrope walk of identity that Frank O’Hara achieved for the category of gayness. He gave it its specific difference within the general category of “being human.” Maybe that’s why Frank made more references to Coca Cola than any other poet of his time. His “Having a Coke with You” begins:

Having a Coke with You

is even more fun than going to San Sebastian, Irún, Hendaye, Biarritz, Bayonne

or being sick to my stomach on the Travesera de Gracia in Barcelona

partly because in your orange shirt you look like a better happier St. Sebastian

partly because of my love for you, partly because of your love for yoghurt

partly because of the fluorescent orange tulips around the birches

The gay references are all there (St. Sebastian, etc.) but it all balances so effortlessly with the simply rendered feeling of human closeness. Frank’s gayness is an expression of his humanity, and the other way around. The two just go together.

As “Hide/Seek” at the National Portrait Gallery shows, the years after Frank O’Hara’s death in 1966 were to see the explosion of gay culture and the rise of an explicit movement for gay rights after Stonewall. There was, understandably, an impulse to define gayness as in absolute opposition and contrast to everything that was straight. But Frank’s victory had already been won. It was always going to be possible, after sharing a Coke with Frank O’Hara, just to be gay and to mean nothing more and nothing less than that. With Frank, gay had gotten comfortable with its specific feel, its specific attitude, its particular place within the pantheon of things-human-beings-can-be. I’m not saying that Frank O’Hara could only have been possible in America. But it is hard to imagine him anywhere else. With this show at the National Portrait Gallery, maybe that fact is something we can begin to treat with the national pride it deserves. • 16 November 2010