Fifty years ago a show of male nude art at a small gallery in Long Island, New York provoked the confusion and disdain of the critics. The poet and art critic John Ashbery complained in New York Magazine, “Nude women seem to be in their natural state; men, for some reason, merely look undressed.” (Ashbery’s concern here might have been masking his own homosexuality.) In a more sympathetic response, Vicky Goldberg noted that the homoeroticism that many of the works provoked cast such art “from its traditions and in search of some niche to call its home.” But it was Gene Thompson at the New York Times who pointed to the deeper concerns of this show when he wrote, “there is something disconcerting about the site of a man’s naked body being presented as a sexual object.” We have thankfully moved beyond such acute prejudices. But even today looking at naked men in art — or elsewhere — can their naked bodies be something more than just naked?

- “Masculine/Masculine: The Nude Male in Art from 1800 to the Present” Musee d’Orsay, Paris. Through January 2, 2014.

“When we look at bodies (including our own in the mirror),” cultural critic Susan Bordo writes in her book The Male Body, “we don’t just see biological nature at work, but values and ideals, differences and similarities that culture has ‘written,’ so to speak, on those bodies.” For Bordo, the body isn’t only composed of DNA, but also holds histories and cultural beliefs, most acutely with notions of gender and sexuality. But often when we think of the heavy meanings placed on bodies, we imagine the female body, which in life and art has a long history of becoming an object of desire and regulation, a symbol and vessel for a host of cultural values. Bordo points out that in film, for example, “we have grown up used to seeing women take off their clothes for sex, or to display themselves erotically, or to be unsuspectingly spied on. The act of getting undressed,” she adds, “is an act of uncovering, exposing; a secret sexual self is revealed.” True for film, and for much of European art for the past several centuries.

When a man undresses it usually is for some useful reason, she argues, such as an action of changing clothes, of exchange one kind of armor for another, for example. Their nakedness has a necessary purpose, an effect of battle or work. For Bordo, these differences have defined our images of nakedness until quite recently. The naked male body, Bordo reminds us, is also layered with histories and values.

•

A year ago the Leopold Museum in Vienna mounted the exhibition Nude Men that drew both critical and patron praise for its approach to the subject. That show firmly anchored the works to historical periods, beginning with the classical idealism of the early 19th century, and ending with representations of the post World War II era. In contrast, the Musee d’Orsay’s show, which draws its inspiration from that earlier exhibition, focuses on themed sections, what the curators call the “aesthetic canons” of the male body, eschewing the “dull chronological” approach in favor of an often confusing and much too slippery focus.

The exhibition is also inspired by a 1995 show at the Pompidou Center in Paris entitled Masculine/Feminine: The Sex of Art that explored the expressions of heterosexual eroticism in 20th century art. But this show’s masculine eroticism is a muted one. We encounter sections on the “Heroic Nude” to “Gods of the Stadium” to “Realistic Nudes” to the less specific and more uncertain sections entitled “In Pain” or “In Nature” or “The Glorious Body.” The effect of these generalized themes is that these male nudes so often escape the history from which they were made. Eroticism, like naked male bodies, has a history as well.

Consider one of the last paintings of the show by the Russian realist artist Aleksandr Deyneka entitled Showers — After the Battle (1944). In the foreground of this huge canvas sits a thick and muscled back of a naked man, staring off to a row of well-formed men showering in the distance. Soldiers we imagine. Their bodies glisten and their playful gestures rendered through a misty haze of light and shadows. The painting’s play of perspectives gives the shower scene a stage-like effect, as if the soldiers are posing and playing for the pleasures of the seated man. And for us. But then, I know this is only my own voyeurism at work here, interpreting this painting within the contemporary moment, imagining it through my own ideas about showers and naked soldiers.

Deyneka was a favorite of Russian leaders, his images of Soviet life from the 1920s on present social and often intimate moments that echo with national pride. Soldiers bathing, workers in the fields, idealized sailors in combat, runners competing in a race, men showering after battles or long days in the factory. But what the Russians saw as celebrations of strong Soviet men in a moment after war, we encounter here as a voyeurism of homoerotic pleasures. Hanging in the show’s last section entitled “The Temptation of the Male,” the painting conjures little of the nationalism it might have had back in 1944, and we aren’t given clues to its past. Instead, sitting there next to David Hockney’s Sun Bathing (1966), its stylized waves and rounded surface of the man’s body reflecting a much different intent, and coupled with a set of small playful line drawings of naked sailors by Jean Cocteau from the 1920s just a few feet away, Deyneka’s soldiers are transformed here into a compelling eroticism, as if we are gazing into a Russian gay bathhouse.

There are many moments like this one as you confront 200 or so naked or nearly naked men, mostly plucked from the history of French art and all seemingly, and inexplicably anchored to the works of contemporary French artists Pierre and Gilles. The pair was crucial to the conceptualizing of this exhibition, and there is a long interview with them in the exhibition catalogue. With eight works included here, one in almost every section, it is clear that their aesthetic approach to the male bodies dominates this show at ever turn.

Pierre and Gilles, who have work in both fine art and advertising, have for over a decade created highly stylized hand-painted photographs presenting dream-like and mythic scenes of beautiful young men and well trained athletes, each mixing B-movie glamour and the surface shine of Madison Avenue with a small dose of surrealism. Whether recreating scenes of Greek mythology or portraying contemporary athletes, their images have become iconic and kitschy gay dreams, filled with a voyeurism that turns the image of naked male models into objects of desire. In this sense, their works turns so much of this show into a pleasurable contemporary eroticism, bodies offered up for their often mysterious and sexual appeal.

But the bodies in their works are creatures of the late 21st century, exploited and eroticized amidst an age when the male body has become a useful object for consumer desires. It is not hard today to see nearly naked men, idealized and offered up for admiration and imitation, from those early Calvin Klein advertisements to the shiny happy young men of the Abercrombie and Fitch catalogs, to a parade of male athletes posing in their own line of designer underwear.

What happens too often as you wander through these galleries is that the particular history and politics recede in our encounters with the variety of bodies we confront, stripping them of more than clothing. Deyneka’s showering soldiers might conjure eroticism for contemporary viewers, but what do we make of this work’s place in the archive of Soviet realism? How is this play of voyeuristic eroticism related to the larger nationalist ideals of the work?

•

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the male body was crucial to academic painting, anchoring the ideals of ancient Greek and Roman aesthetics. One of the more compelling works early in this show is Jacques-Louis David’s Patroclus (1780). David, the icon of early 19th century Neoclassical painting, used heroic, naked males in many of his historical paintings, composing large canvases filled with muscled subjects, their crotches often covered in subtle ways, all rendered with realist precision. Unlike David’s more crowded historical scenes, this work offers a quiet intimacy between viewer and the subject sitting on the ground in a weakened state, his torso twisted away from us, leaving us gazing at him from behind. In Homer’s Iliad Patroclus was the comrade of Achilles fighting alongside him in the Trojan Wars where he was killed. Their relationship has often been considered a romantic one. The painting conjures the beauty of Patroclus’ body as something idealized, as if David is asking us to gaze upon the defeated warrior in the same loving way as Achilles himself might have done. But beauty and nakedness here serves another purpose as well: a heroic ideal that captures not just our attraction but also our empathy.

Not far from this work you find Picasso’s Adolescents (1906), a muted orange oil painting of two naked figures against a flat background. They float on the canvas, their bodies blending with the atmosphere around them, their bodies shaped in thick lines. Just around the corner is Gustave Moreau’s Prometheus (1868), the figure bound to the mountain’s edge, his body taunt and tired, his face determined as he looks off into the distance, echoing more the image of a Christ figure than that of a Greek god. The work is distinctively Moreau, with its muted colors and elongated body, flesh tones and atmosphere blending.

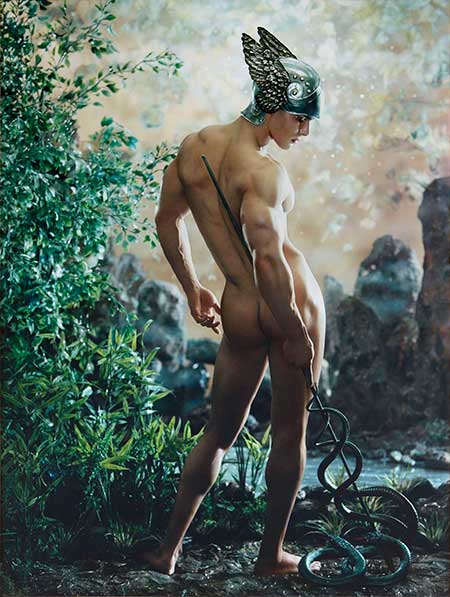

Floating amidst these works is the ornately framed photograph Mercury (2001) by Pierre and Gilles. Mercury graces the promotional materials for the show alongside Jean-Baptiste Frédéric Desmarais’s The Shepherd Paris (1787), the beautifully elongated body of the subject conjuring classical idealism, connecting beauty and desire with the mythical figure of Paris within the post-revolutionary France. While Mercury draws from such earlier aesthetics, it clearly transforms them. The mythological figure looks decidedly contemporary like a thickly muscled gym boy. He poses with his back towards us as he twists his head — flaunting his kitschy winged helmet — towards the ground, gazing at the tip of his staff. Behind him a mystical landscape blurs in the background.

What are we to make of such juxtapositions of periods and intents? Surely Picasso’s nameless adolescents held a different meaning than the naked gods and warriors of the 19th century, and Pierre and Gilles’ static, technicolor fantasy of Greek mythology. Stripping these bodies of their cultural and historical meanings turns them into eroticized objects that feel quite contemporary.

In losing the history we lose the politics as well. Think for example of the naked and eroticized images of male bodies at the heart of the culture wars a few decades ago in the United States. These conflicts were acutely visualized in the work of gay artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe, where male nakedness and gay eroticism provoked an anxiety over sexual politics and artistic freedom. There is only one image of Mapplethorpe in this show, the relatively calm Ajitto (1981), a simply composed image of a naked man wrapped in upon himself perching on a small table. It is an image that echoes Hippolyte Flandrin’s famous 19th century painting Study (Young Man Sitting by the Sea) 1836, and Wilhem von Gloeden’s photographic reproduction of the painting done on the rocky coast of Italy in the early 20th century. Looking only at these three works in their compositional reverberations leaves us blind to the different meanings they evoked in their time and place.

Consider a large bronze statue entitled The Active Life (1939) by the German artist Arno Breker. The sculpture poses a naked and sinewy athlete as if in mid stride along the beach, one hand perched on his waist, the other out stretched as if inviting us to look. It is a figure of composed strength and balanced form recalling the best of the classical aesthetics, but decidedly modern in its gesture and facial expression.

Hitler employed Breker as the official sculptor of the Third Reich. In a photograph of Hitler standing in the Trocadero in Paris, the Eiffel Tower off in the distance, the German chancellor is flanked on one side by his favorite architect Albert Speer and on the other by Brecker. This sculpture is just one example of the many men the artist created for the Third Reich, their manly and muscled nakedness symbolizing the strength of the masculine fascist body and beliefs in racial purity and German superiority. It was a mixing of idealization with national ideology that goes unnoticed in this show.

Breker’s The Active Life is part of the gallery “Nude Heroes” amidst other works filled with sinewy figures of 19th century academic paintings from Achilles to the biblical David to Alexander Cabanel’s Fallen Angel (1847) with its figure reclining in repose of shame and flirtation. And not far from Breker’s ideal man is Pierre and Giles’ Hercules Fighting the Hydra (2006), the static figure frozen with his back towards us, his left hand raised with a caveman club looking too well staged to do any damage despite his bodybuilder girth. Admire my muscles, the work asks of us. And so too might Breker’s sculpture, but for much different reasons. Male nudity and politics are not so easily disentangled.

I suspect it would have been too disturbing to place The Active Life in the latter sections of this show such as “Objects of Desire” or even alongside Deyneka’s naked soldiers? We can’t really desire Fascist idealism these days, I suppose. But such acutely slippery moments in this show underscore how limited the themed sections really are in contemplating naked men. What we are left with is an eroticism that escapes history. This show confronts us with images of male nudity as a contemporary experience, ignoring the intersections of aesthetic and political values that have given shape and meaning to these bodies over the past 200 years. This historical blindness leaves us sitting there, like Deyneka’s soldier, staring at the surfaces of all these naked bodies. • 25 November, 2013