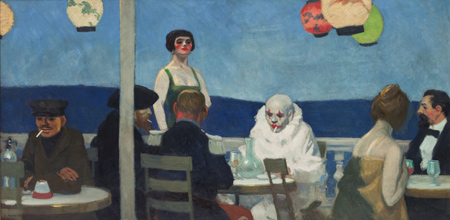

Is he a cliché? That’s the question you keep coming back to when you look at the paintings of Edward Hopper. On the face of it, the current show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, “Modern Life: Edward Hopper and His Time,” doesn’t help answer the question. The show gives us paintings like “Soir Bleu” from 1914. We’re at a café in France somewhere. Patrons sit at the tables. Right there in the middle, facing us, is a clown. He is wearing a white, frilly get-up and his face is painted white, too, with red lips and a couple of red stripes down the eyes. He is smoking a cigarette. This may, in fact, be the sad clown we’ve all heard so much about. I’ve toyed with the idea that “Soir Bleu” is making fun of itself. Or maybe it is making fun of us, the viewer? But, no. Hopper is a painter without any sense of humor, which is a troubling fact. He paints without wit, without self-awareness. We may have to accept the fact that Hopper painted the sad clown smoking a cigarette in the café because he felt it to be a poignant scene. He was so moved by the depressed clown that he went and painted one of the silliest paintings of the era.

- “Modern Life: Edward Hopper and His Time.” Through April 10, 2011. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Hopper spent time in Europe during the 1920s. He was living in Paris on and off when the ex-pat scene was at its very height. Impressively, it doesn’t seem to have affected him much at all. That’s what you want to admire about Hopper. His Americanness was so real, and so deeply rooted, that continental trends and ideas bounced right off him. He was still trying to find his way as a painter in the ’20s. He had every reason to dabble in the trends. But he didn’t. He didn’t want to be an abstract painter. His mind was not blown by Cubism. He did not succumb to the excitement of any avant-garde. How many of us have ever shown that kind of resolution? It is not that Hopper lacked ambition. He wanted to be a great painter. He wanted to be relevant. And yet he stuck to his realism, to his representational style, to everything that was being rejected by so many of the celebrated painters of his day. Admirable.

Still, we wonder. Did Hopper stick to his guns for all the right reasons? Or was it all he could do? Was he an ugly American, so wedded to simplistic imagery that the finer points of Cubism or abstract painting would have been over his head? Did Hopper rely on cliché because that was all he understood?

The fact that so many of Hopper’s paintings make good postcards and prints makes the worry about cliché even stronger. His most famous painting, “Nighthawks” (not included in the Whitney show), the one with the people sitting in a diner late at night, has become global kitsch. Everyone has seen the version with James Dean and Marilyn Monroe, or the thousand and one different puns and knock-offs that resonate throughout popular culture. The accessibility and near-universal appeal of that painting, like so much of Hopper, starts to make a person suspicious. The common denominator of such work must be pretty low if the painting works in a video game or on a TV show without even missing a beat.

Clement Greenberg, the great American critic of postwar painting and the champion of the Abstract Expressionists, simply called Edward Hopper a bad painter. But it was impossible for Greenberg to dismiss Hopper completely. Even though Hopper is a terrible painter, Greenberg famously remarked, he is a great artist. That is a surprising statement. Greenberg had every reason to hate Hopper all the way through. After all, Greenberg’s primary heroes of painting had completely embraced abstraction — artists like Pollock, de Kooning, Newman. They had become aware, as Greenberg saw it, that the highest expression of painterly skill was in showing the flatness of painting, the material process by which paint is applied to canvas. They were painting about painting. Hopper, however, was painting about people in the world; sometimes even about clowns in the world.

Greenberg never expressed it this way, but I think he recognized that Hopper was dealing emotionally with the same thing that the Abstract Expressionists were dealing with formally. Hopper seems to have been fascinated with the fact that all people can really know about each other are what they show on the surface. The Abstract Expressionists were dealing with painting as surface; Hopper was dealing with people and places as surface. Everybody is nothing more than what they look like, how they behave. And yet, we know that to be human is to inhabit our own interior, to be in our own head, to feel a million different emotions every day that we never get the chance to express fully, even to ourselves.

Hopper paints that situation. He paints individuals of great inner depth with the full knowledge that that inner depth itself can never be painted. Because he is painting people as surfaces, he is going to flirt with cliché constantly. When he gets it wrong, when he tries to be too evocative, too objective, the whole thing falls apart. It gets corny. Like the clown. But that is the danger of painting surfaces that only hint at the underlying depths.

And that is the difference between a terrible painting such as “Soir Bleu” versus a great painting like “New York Interior” (1921). A woman sits on the bed with her back to us. She is heavily involved in the process of what looks to be the sewing of a dress. Her hair is parted in the middle and falling down forward as she concentrates. She has become one with the simple task she is performing. That kind of thing happens to all of us every day. And there it is on the canvas.

In “Soir Bleu,” Hopper goes too far, he shows too much. He is hitting us over the head with the idea that the clown, with his outwardly clowny appearance, is actually hiding a lonesome and troubled man. It is just plain dumb. But “New York Interior” gives us a woman wrapped up in the process of acting and doing and thinking and dreaming all at once. We don’t even have the faintest glimpse of what could be going on in her head, where her thoughts have wandered as she sews her dress. But we know that she is going somewhere, mentally, that her thoughts are wandering. It is in her gesture, in the absent-minded way she pulls the thread. We know that there is an entire universe of interiority unfolding within that person as she does what she does. We can see it because Hopper has so perfectly captured her in that moment of hiddenness without bursting the shell, without rupturing that thin but impenetrable membrane between the inner and outer. “New York Interior” is dangerously close to being a sappy and sentimental study of a lonely young woman. It is a great painting because it hovers so very close to being a cliché without ever crossing that line.

• 14 December 2010