In retrospect, it was fitting that I saw James Cameron’s new film Avatar at an IMAX 3-D theater in Las Vegas. Las Vegas is not a place for those with any nostalgia for simpler times. In Vegas, reality is something to be fabricated, played with, and reproduced in as many ridiculous ways as someone is willing to pay for. Robert Venturi, the architect who penned the famous postmodern manifesto Learning from Las Vegas, was never a fan of Minimalism or austerity. In response to Mies van der Rohe’s architectural dictum “less is more,” Venturi quipped that “less is a bore.”

Likewise, Cameron has never been a prophet of restraint. From Terminator to Titanic, he likes things big, expensive, messy, and new. It was, thus, fully expected when Cameron told Dana Goodyear of The New Yorker that Avatar is, “the most complicated stuff anyone’s ever done.” Cameron’s goal, in short, is to completely revolutionize cinema. He also thinks of cinema as largely a visceral and visual thing. Emotional complexity is not his strong suit. He wants people to see something new, like when they first discovered the moving image.

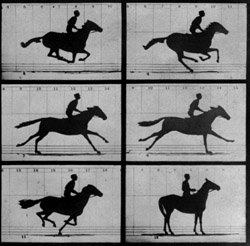

It has been a long time since Sallie Gardner trotted into history. She was the horse that Ed Muybridge photographed with multiple cameras at a racetrack in Palo Alto, creating what is often considered the first motion picture. That was 1878. Cinema was mostly gadgetry then, the next step for the possibilities opened up by photography.

In those days, the content of a film wasn’t all that important. The point was the motion, the fact that a temporal sequence could be captured and re-shown. All of a sudden, the fleetingness of events had become less fleeting. Still, the technology could only handle events of a short duration. There wasn’t much time to tell a story. So early films focused on happenings: the bustle of street life, the fastaction of a locomotive, animals doing animal things. One of the more famous early films, made with one of Thomas Edison’s Kinetographs, simply shows a man sneezing. (Many of these early films can be found at the Library of Congress’ YouTube library). The audience would ooh and ahh at the sheer spectacle and novelty of these brief clips. It was sensational, simply for the fact that motion pictures were a new way to experience experience.

There are tons of (possibly apocryphal) stories of early filmgoers running away from the theater in panic after viewing a locomotive coming right at them from the screen. It takes a minute to adjust when reality changes. We aren’t hardwired to watch films, or to do many of the other things we currently enjoy doing. So there’s a shock effect that comes with the expansion of horizons. Learning how to watch movies means learning — if ever so slightly — how to tweak your ability to experience the world.

Once the necessary adjustments are made, human beings are talented at getting on with things. After we had seen a few locomotives steaming by and the handful of sneezes it was time to move on. We wanted to put the whole complexity of life lived up on the screen. And that’s what we’ve been doing for more than a century.

It is fitting, then, that the story told in Avatar is so very dumb. It’s the standard dehumanizing evils of modernity versus authentic people of the forest tale. But just like in the good old days, the story isn’t what we’re there for. We are there to see reality expanded once again, to see digital technology create a coherent world that never existed anywhere on the corporeal plain. A good story would get in the way. Cameron obliges us by not bothering. Instead, he creates a glowing forest landscape filled with fluorescent plants and animals that pop and whiz and jump around the screen. I heard oohs and ahhs in that theater in Vegas. I can’t say when I last heard such genuine, guttural expressions of human amazement in a movie theater. Our minds were being, if gently, blown. That is worth something, to have one’s sense of reality tweaked in a format that has otherwise been so comfortable for so long. What happens in the movie? Who cares? But dammit if Sallie Gardner doesn’t ride again. • 24 December 2009