Long has the fate of mankind been tied to apples. They got Adam and Eve banished from Paradise. With the apple, Johnny Appleseed tamed the New World. And then, in the late 19th century, Paul Cézanne declared he would paint the otherwise unremarkable fruit and “astonish Paris with an apple.”

The World is an Apple: The Still Lifes of Paul Cézanne. The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia. Through September 22, 2014.

Cézanne did just that. His paintings of apples confused critics and art enthusiasts alike. People were astonished that apples could look so ugly, and be so poorly painted. Some thought Cézanne’s still lifes were actually a joke, or an insult. It is difficult, looking at Cézanne’s paintings today, to feel the full force of that outrage. But there were certain artistic standards in the late 19th century. Painting that came out of the official Academy of Art (Écoles des Beaux-Arts) was expected to look a certain way. Brushstrokes, for instance, were supposed to be smoothed out and worked, more or less, into the finish of the painting. A glossy and well-varnished surface was expected. One look at the paintings currently on display at The Barnes Foundation’s Cézanne exhibit (The World Is an Apple: The Still Lifes of Paul Cézanne) is enough to see that Cézanne was not an Academy painter. He was making a point of being rough and crude.

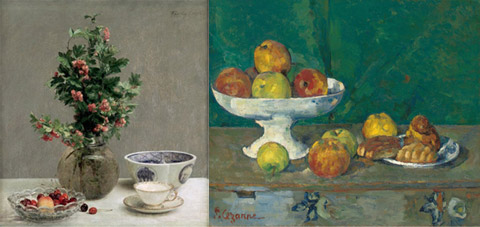

There is a helpful juxtaposition of paintings in the catalogue to the Barnes Foundation exhibit. Curator Benedict Leca presents a picture by Henri Fantin-Latour called Still Life with Vase of Hawthorn, Bowl of Cherries, Japanese Bowl, and Cup and Saucer (1872). Fantin-Latour was a successful and well-respected Academic painter in his time. His still life is skillfully done. His rendering of the Japanese bowl and the cup and saucer is, in particular, masterful in its photographic details. The reflections on the bowl are perfect. Turning to Cézanne’s 1873-77 painting, Apples and Cakes, the contrast really is incredible. Cézanne’s painting is all coarse daubs and bold patches of color. There is no attempt at photographic effects. You can see all the brushstrokes; some look like they might have been applied directly to the canvas with a palette knife. You can tell the painting represents apples and cakes, but there is also no mistaking that this is paint applied to a canvas. The illusions of Fantin-Latour’s still life have been left far behind.

Left: Henri Fantin-Latour’s Still Life with Vase of Hawthorn, Bowl of Cherries, Japanese Bowl, and Cup and Saucer. Right: Paul Cézanne, Apples and Cakes (Pommes et gateaux), 1873–77, oil on canvas, 18 1⁄8 × 21 3⁄4 in. (46 × 55.2 cm), Private Collection, © Christie’s Images Limited (2005)

.

The question is, then, why did Cézanne want to astonish Paris with crudely painted apples?

One answer is that he was tired of Academic painting. Plenty of other artists felt the same way. They were looking for something fresh, something different. There is the fact, also, of photography, which was becoming more sophisticated with each passing decade of the 19th century. What was the point of laboring long and hard on photographic-looking paintings when an actual photograph could do the same thing in an instant? Painting in the late 19th century was, therefore, at a crossroads. It was the right time for radical ideas, for paintings that looked completely unlike the glossy and studied affairs coming out of the official Academy.

That explains the desire for new directions in painting. But it doesn’t explain why Cézanne went one direction rather than another. Why did Cézanne decide to make still lifes that look so peculiar, so specifically Cézanne-ish? And what is it, exactly, that makes a Cézanne look like a Cézanne?

Paul Cézanne, The Kitchen Table (La table de cuisine), 1888–90, oil on canvas, 33 3⁄8 × 39 1⁄2 in. (84.8 × 100.3 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF 2819

One thing everyone agrees about is that Cézanne liked his painting surfaces rough with paint. He generally did not varnish or glaze his paintings. He also didn’t care much for “correct” perspective. Look, for instance, at The Kitchen Table (1888-90). The left corner of the table doesn’t even match up with the right corner. And the floor of the kitchen doesn’t recede properly into space. Cézanne didn’t care. He wanted the painting to look this way. He wanted you to feel – when looking at the painting – slightly off-kilter, like the canvas can’t quite hold what is inside it and the kitchen might spill forward out of its frame.

Cézanne also liked to blur lines and boundaries within his paintings. In Apples and Cakes (1873-77), there is a green object, probably an apple, at the back of a white dish of fruit. The apple is the exact color as the wall behind the table. So, it looks as if the wall, in the background, has simply bled into and become part of the bowl of fruit in the middle ground. In Still Life with Seven Apples and a Tube of Paint (1878-9), Cézanne has scraped at the apples with some sort of knife, mixing the colors and boundaries of the middle apple into the apples next to it. In Still Life with Carafe, Milk Can, Bowl, and Orange (1879-80), the carafe barely exists, since it merges into the colors and shapes of the wall behind it and the other objects nearby. Many things seem to be merging in Cézanne’s paintings. Objects merge with one another. Background and foreground merge. Space itself seems to tighten and overlap.

It is as if Cézanne painted still lifes to show that individual objects sitting on a table are not individual objects at all. Sure, an apple is just an apple. But in Cézanne’s still lifes, an apple isn’t just an apple. It is also all the other apples. And it is the table and jug and the pitcher and the wall behind the table. Every object is implicated in every other object. To look at one object you have to look at all the others. To confront one individual thing, you have to confront a whole world. If you look back at Henri Fantin-Latour’s Academic still life again you can see the difference. Fantin-Latour’s objects, his vases and bowls and cups, are quite happily the differentiated objects that they are. It is a lovely painting. Cézanne’s still lifes are not lovely in the same way. But they are intense. Cézanne’s objects do not hold still like Fantin-Latour’s do.

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Carafe, Milk Can, Bowl, and Orange (Carafe, boîte à lait, bol et orange), 1879–80, oil on canvas, 21 1⁄4 × 23 3⁄4 in. (54 × 60.3 cm), Dallas Museum of Art, 1985.R.10, The Wendy and Emery Reves Collection.

This holistic approach to art, where individual objects point beyond themselves, was not invented by Cézanne. Holism is an idea as old as the Pre-Socratic philosopher Parmenides in the Western tradition. And it was an idea buzzing around the French Mind quite actively in the middle and late 19th century. For example, Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables was published in 1862. In an abandoned preface to the book, Hugo had written:

This book has been composed from the inside out. The idea engenders the characters, the characters produce the drama, and this is, in effect, the law of art. … Destiny and in particular life, time and in particular this century, man and in particular the people, God and in particular the world, this is what I have tried to include in this book; it is a sort of essay on the infinite.

We can look at Cézanne’s still lifes in roughly the same way: “Fruits and in particular the apple, kitchens and in particular this kitchen, rooms and in particular this room, God and in particular the world, this is what I have tried to include in this painting; it is a sort of painting of the infinite.” Hugo created his essay on the infinite with words that build into stories. Cézanne was trying to do the same thing with paint that builds into visual scenes. By messing with perspective and tonal values, Cézanne created the feeling in his paintings that all the individual objects in the scene are connected and interpenetrated.

Around the same time Hugo was writing Les Misérables, Baudelaire was working on his great poem cycle, The Flowers of Evil. One poem from that cycle, Correspondences, reads:

Like long echoes that intermingle from afar

In a dark and profound unity,

Vast like the night and like the light,

The perfumes, the colors and the sounds respond.

There are perfumes fresh like the skin of infants

Sweet like oboes, green like prairies,

—And others corrupted, rich and triumphantThat have the expanse of infinite things,

Like ambergris, musk, balsam and incense,

Which sing the ecstasies of the mind and senses.

Cézanne was trying to paint apples so that they, too, might have “the expanse of infinite things.” In his poem, Baudelaire links the idea of expanding into the infinite with ecstasy. The correspondences between all things in nature “sing the ecstasies of mind and senses.” There is a feeling of melting here, of losing oneself in the great dissolution of the infinite.

Cézanne was attracted to this idea in his painting. But Cézanne didn’t want to lose his apples completely to the infinite. His canvases don’t fall apart into pure abstraction, or formless masses of color. Cézanne wanted apples still to be recognizable as apples. One of the things Cézanne objected to in Impressionist painting was the lack of structure, the fact that every object seemed to dissolve completely into a play of light. Cézanne sometimes spoke about wanting to make Impressionism into something “solid and enduring.” So, he painted solid apples with solid lines. And then he created an atmosphere around those apples that suggests the fact that every apple is connected to every other apple, that all things are contained in an essential oneness.

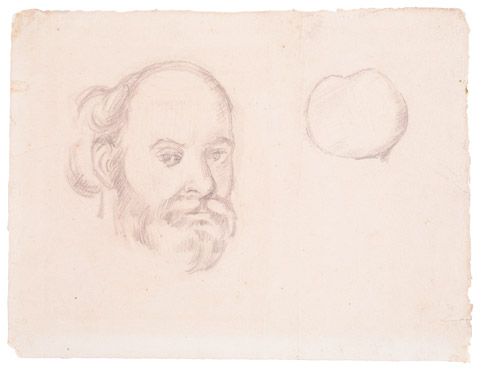

Self Portrait with Apple, graphite on paper, 6 3/4 x 6 13/16 in. Cincinnati Art Museum, through the generosity of the Oliver Family Foundation. Gift of Emily Poole

Walter Benjamin noticed a similar ambiguous feeling about dissolution and infinity in Baudelaire’s poetry. Benjamin thought this ambiguity the result of Baudelaire’s ongoing struggle with Modernity. Perhaps this was true of men like Victor Hugo and Cézanne as well. They were attracted to the way that the modern world was breaking down boundaries; socially, politically, aesthetically. But they feared it, too. When so many boundaries are broken down, an abyss opens up. Baudelaire often toyed with the abyss in a literal, physical way. He was obsessed with crowds. He would walk the streets of Paris, taking in the chaos of city life. Sometimes, Baudelaire would abandon himself in manic ecstasy to the forces of the crowd and city. “Of all the experiences which made his life what it was,” Benjamin wrote in “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,” “Baudelaire singled out being jostled by the crowd as the decisive, unmistakable experience.” Being jostled by the crowd is to be shaken in your subjectivity. Anyone who has ever been caught in a teeming crowd knows the feeling. It doesn’t matter where you want to go—the crowd takes you. In his poetry, Baudelaire experimented with different responses to this jostling. “Baudelaire battled the crowd,” wrote Benjamin, “with the impotent rage of someone fighting the rain or the wind.”

Cézanne’s love of structure, the hard black lines in his paintings, are his own version of Baudelaire’s battle with the crowd. The structural integrity of the pears and the pitcher in Pitcher and Plate with Pears (1895-8), for instance, is something you wouldn’t expect to see in a still life by Monet. It seems that Cézanne was trying to maintain the integrity of individual objects even as he explored holistic ideas. Cézanne did not want to show objects dissolving into the infinite so much as objects that only exist as objects within the structure of the infinite. The idea is that we cannot see or know the whole without the individual and we cannot see or know the individual without the whole. Cézanne, like Baudelaire, was trying to hold that line against all the chaotic forces assailing art and society in late 19th century Europe.

That’s why apples were such a big deal to Cézanne. Once, he made a sketch. It is a self-portrait. On the left-hand side of the sketch is Cézanne’s head. On the right is a large apple. For all his experiments in radical new ways of painting, Cézanne did not want to lose sight of the reality of that apple. In losing the apple, he would have lost himself. • 25 June 2014