In Camera Lucida, his mediation on the history and nature of photographs, Roland Barthes wonders about the medium’s “essential feature” that distinguishes it from “the community of images,” from paintings, drawings, or etchings, for example. Barthes writes:

To see oneself (differently from in a mirror): on the scale of History, this action is recent, the painted, drawn, or miniaturized portrait having been, until the spread of Photography, a limited possession, intended moreover to advertise a social and financial status — and in any case, a painted portrait, however close the resemblance. . . is not a photograph. Odd that no one has thought of the disturbance (to civilization) which this new action causes.

I’ve always been struck by this word “disturbance” Barthes uses to describe those early encounters with photographic portraits. The word evokes not only a cultural ripple in the history of image making, but also conjures a psychology of looking, as if photographs unsettled how we see ourselves.

- “Julia Margaret Cameron”

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Through January 5, 2014.

In many ways “disturbance” is a good word to describe Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographs. The 35 photographs in this show hold the familiar patina and look of mid-19th century photography — the grey, uneven tones and those serious gazes that present a certain concentrated solemnity. But what disturbs is how these portraits exude a more contemporary psychological reality, an often-startling intimacy between camera and subject accentuated by a conscious play with the focus of the image.

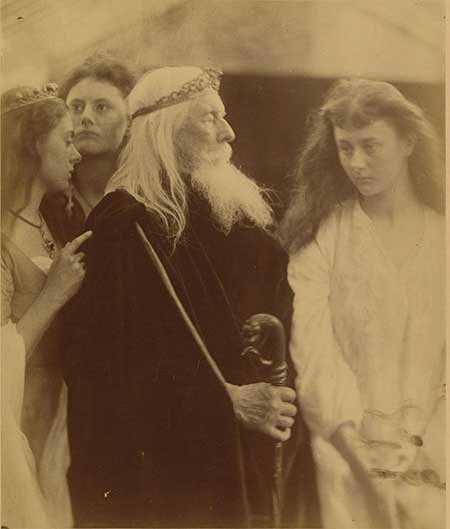

King Lear and his Three Daughters

The show starts where Cameron’s biography often starts: Christmas 1863 when her daughter and son-in-law gave the 48-year-old Cameron her first camera, writing “it may amuse you, Mother, to try to photograph during your solitude at Freshwater.” Cameron’s six children were grown and the camera was a gift of distraction.

Freshwater was on the Isle of Wight off the cost of England, and Cameron and her husband had arrived there after a life of spent on the outer margins of the British Empire. She was born in India to a French mother and an English father who was an official in the East India Company. At a young age, she went to live with her grandmother in Versailles, France, and later traveled to South Africa. At 18 she returned to Calcutta where, in 1836, she married Charles Hay Cameron, 20 years her senior and a prominent British jurist in the colony. After more than a decade, they returned to England with six children and trunks full of silk fabrics, ivory sculptures, and exotic teas that would captivate and intrigue their circle of friends in London.

But a few years later they packed up again, left the cosmopolitan life of London and moved to a cottage next to the poet Alfred Tennyson on the small island in the English Channel. The seclusion and quiet must have proved daunting for Cameron, a curious and energetic woman who enjoyed her adventures and travels across terrains far beyond England. The gift of a camera, in effect, replaced Cameron’s many years of travel for a different kind of adventure: one concerned with experiments in light and chemicals.

The camera her daughter and son-in-law gave her that winter was a heavy machine, awkward to move around, made of wood and the size of a large birdhouse. It was the most modern of its time. We can easily forget today how arduous and dangerous the process of photographing was back then. The glass plates used to expose the image (the forerunner to film) were their own chemistry lab, requiring a coating of a thick and flammable collodion solution, followed by a quick dash to the camera to insert the class behind the lens and expose it to the light before the plate dried. Then, through a series of sliver nitrate washes (the fumes could be deadly) and drying, washing and drying again, the glass negative was ready to transfer its image to the prepared albumen paper that was brushed with a frothy mixture of egg white and silver nitrate to give the paper a glossy texture. The plate was placed on the paper, exposed to the sun, and then, it too was washed and let dry. At any one point in this process, the photographs could easily be destroyed. This mixture of science and art burdened these practices with certain standards of skill. Photography was still considered a scientific experiment; it’s practitioners more akin to chemist than artists. What constituted a good photograph was as much about the process as the composition.

While there is little evidence that she was much interested in visual art before the 1860s, Cameron took to this process with her usual energy. Her interest was in what this process can create more than what it should create. There is a clear sense of experimentation with her photography, particularly with the aperture. She preferred long exposure times of a few minutes rather than the more usual few seconds. The effect of this created blurred parts of the images — backgrounds fade into darkness, foreground details of jewelry or clothing shimmer in their abstraction.

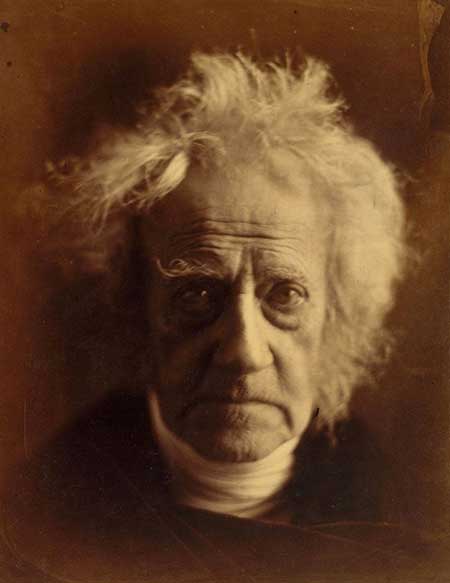

Sir John Herschel

Cameron put her friend Tennyson in a posture of distant contemplation, a lace collar framing his head, fading as it winds its way around his neck, its distinct details flattening to indistinctive shapes and light. The attention is on his eyes — as it is in many of her portraits. Take the botanist and inventor Sir John Herschel, the man’s aged face looks both bewildered and determined, his hair, which Cameron had him wash just for this image, flows like a hazy white cloud around him. There are other great men here, all friends of Cameron, who sat for her camera, some calling the experience excruciating in the ways she demanded a stillness for the exposure time, or the precision of gestures she hoped to get. What she did get are portraits that capture not just people but psychologies, and you have to keep in mind that these photographs are not the best from a long series of shots. Most were captured in just one exposure.

Compared to the standards of photographic portraits of her time Cameron’s famous men look utterly frail. Consider Oscar Rejlander’s portrait of Tennyson done a few years before he sat in front of Cameron’s lens. Rejlander, a successful London photographer, gives us a man in a controlled gesture, his face and torso in a posture of dignity. He could be Abraham Lincoln. Or even the Victorian Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. There was a grammar to such portraits, a posture of what it means to sit for a camera, a realism that offered its own performance. Even in Cameron’s portraits we get a performance, but one that is more psychological than cultural. We encounter the faces of Victorian England’s great men as if they were butchers or shop owners, unmasked by whatever grandness the camera was meant to bestow. It is a different kind of realism that feels more akin to the late 20th century than of middle of the 19th.

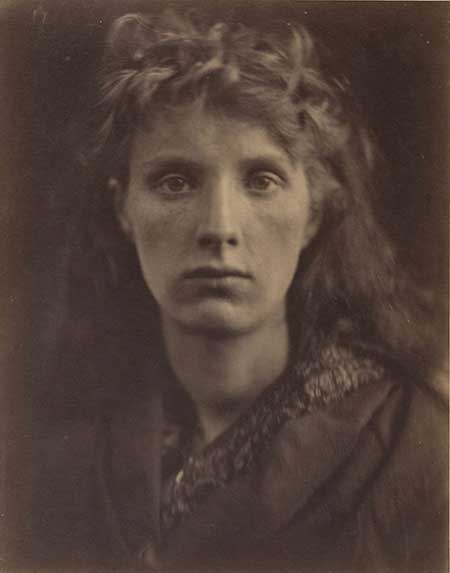

Sappho

If her famous men were caught in their ordinary humanness, her women take on the utterly mythic, a poised and sensitive beauty. In “Sappho,” for example, the woman’s profile is acutely detailed against the dark background, the light washing along her forehead and nose. Her jewel necklace and embroidered dress glimmer with less precision. The work recalls that of early Renaissance paintings. Or more accurately, it conjures the Pre-Raphaelite aestheticism of the era that Cameron knew quiet well. Sappho here is believed to be a housemaid at Freshwater, transformed into something more ethereal, the image of a Greek poet. In many of these female portraits, Cameron turns the margins into the ideal, and the ideal into the human.

The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty

In “The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty” we encounter the longing stare of a woman, her face illuminated with contrasting shapes of light and shade. But it is her gaze that we can’t pull ourselves away from, for it is a gaze so unique in the history of 19th century photography with its assertive directness calling us not so much to admire her but rather to regard her. With many of her women, Cameron inverts the dynamics between female subject and viewer, such that these anonymous models and maids (and sometimes friends and family) exude the same compelling intimacy and psychological complexity as the male writers and scientists. This alone must have disturbed and delighted many.

But nothing disturbed the critics more than her lack of technical purity. “Mrs. Cameron exhibits her series of out-of-focus celebrities,” began one critic of her work in The Photographic Journal in a tone of condescension. He continued: “We must give this lady credit for daring originality, but at the expense of all other photographic qualities,” adding: “In these pictures, all that is good in photography has been neglected and the shortcomings of the art are prominently exhibited.” While not always the case (many considered her works the “nearest approach to art” in photography), the mostly male critics had little confidence in these photographs produced by the hands of a woman. Her experiments with aperture and light, and rejection of many standards within the genre of photographic portraiture, were viewed with a dubious eye.

Cameron was often infuriated by these criticisms. In a letter to a friend, she railed against such judgments: “What is focus and who has the right to say what focus is the legitimate focus?” Her comment defends more than the blurry edges of her photographs. I hear in her question a defense of her way of looking, asserting claims over the arbitrariness of photographic aesthetics, making an argument for other ways of imaging what a portrait can show us.

We often want to place Cameron’s photographs in the boundaries of English Victorian society. As the press materials for this show proclaim, Cameron’s portraits with their experiments in technique and inflected with the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics, offer us a “mirror of the Victorian soul.” But oddly, such proclamations ignore the artist’s experiences beyond England, where she spent so much of her life. In the mid 1870s she left England again, for the final time, and returned to India. There are only a few photographs from these later years, some of locals, cast in dark shadows, looking much more distant than her portraits done on the Isle of Wight. But throughout this show there is the lurking reality that these photographs were done by a woman aware of England’s margins, where the word “focus” held a layered meaning beyond the delicate workings of a camera lens. • 8 October 2013