William Blake didn’t see with his eyes. He was an artist of visions, not vision. Visions happen in the brain and other places of the imagination. Vision is a physical matter, having to do with retinas and light. Blake’s vision was fantastic. It brought him a constant stream of images, more often than not from the Bible. He saw the world as illuminated and pulsing with Joy and Sorrow, heavenly light, and the dark gloom of Hell. The world of visions was truth for him. He said, “Imagination is the real and eternal world of which this vegetable universe is but a faint shadow.”

It is possible that William Blake was simply a lunatic, mad from start to finish. But that doesn’t matter. As Wordsworth once observed of Blake, “There was no doubt that this poor man was mad, but there is something in the madness of this man which interests me more than the sanity of Lord Byron and Walter Scott.”

Blake didn’t think he was crazy. He saw himself as the ultimate realist. Thus the central paradox of his art. Blake thought that the material world the rest of us live in was simply an illusion. His realism was a mystical realism. In Blake’s reality, mountains had faces, spirits flittered about willy-nilly, and the body was but a temporary casing for the soul. At the Morgan Library in New York City — through January 3 — you can get a good sense of how that reality looked.

The drawings are simple and ethereal. Blake trained for many years as an artist in order to finally produce work that looks untrained, even childish. He knew, though, what he was doing. You’ll see a love of line, though there is nary a straight one to be found. Blake liked his lines wavy and freehand. He saw every one as an “outline.” He didn’t worry much about filling in those lines, as would a traditional artist of the time. Through his “outline” technique, Blake was able to create shape and form and mass without worrying about the specific painterly tricks of shading, perspective, and the like. Such skills, to Blake, served the needs of the eye and not the mind.

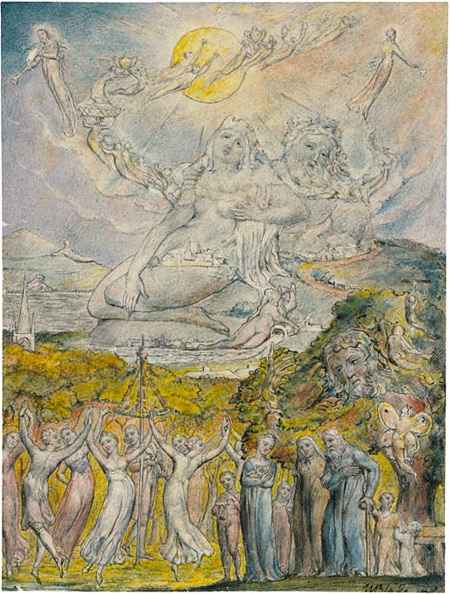

In “A Sunshine Holiday,” Blake’s outlining technique is in full display. The scene is bucolic, part of a series of drawings that illustrate Milton’s early poems “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso.” A group of revelers dance around a Maypole in the foreground. These figures are reasonably fleshy. Blake fills them out and gives them some color. The old man, in particular, is drawn with shading and a relative abundance of detail. But a butterfly woman off to the right, who probably represents the soul, is more airy. A parade of figures rising into the sky above her are in greater outline still. They shuffle off their mortal coil, literally. They lose matter and form as they rise. That is, they become more real as they become less corporeal. In this, Blake was like a Neo-Platonist from the old days.

Plotinus, the famed Neo-Platonist philosopher of Late Antiquity, used to complain about having a body at all. It was a terrible encumbrance. Body is matter, dumb and inert in its essence. Plotinus wanted to ascend to a purer realm, a godly non-place with neither physical things nor beings. He called it The One. So utterly pure and consistent, it has no characteristics. It just is. That is where Plotinus wanted to go. Blake wanted to follow him there.

This is a funny goal for an illustrator to have. You can’t draw The One. Blake’s reality was thus, at its highest level, beyond representation. To portray this world, Blake would have had to draw his way back to a blank page. That is a rather challenging form of realism. His technique of “outlining” was the compromise, the halfway point between a fallen creation and the utter simplicity of The One.

Of course, every Christian Neo-Platonist has to make some peace with the world of creation. The lower must always have some fundamental connection to the higher. We have to do something here on Earth before we get to fly off with the angels and merge into the infinite oneness. It was a peculiar Blakean variant on both Christianity and Neo-Platonism to envision the time spent on Earth as best spent in the company of mirth, of dancing and having a grand ol’ time. Little does Blake dwell on sin, since sin is embedded in creation itself and not so much in the particular actions of men. The best way to avoid the devil is to laugh and take a holiday. The childlike nature of his style was a study in innocence as morality. It is practice for transcending the world completely. We can only hope he finally found his way to that giant blank page in the sky.

• 6 November 2009