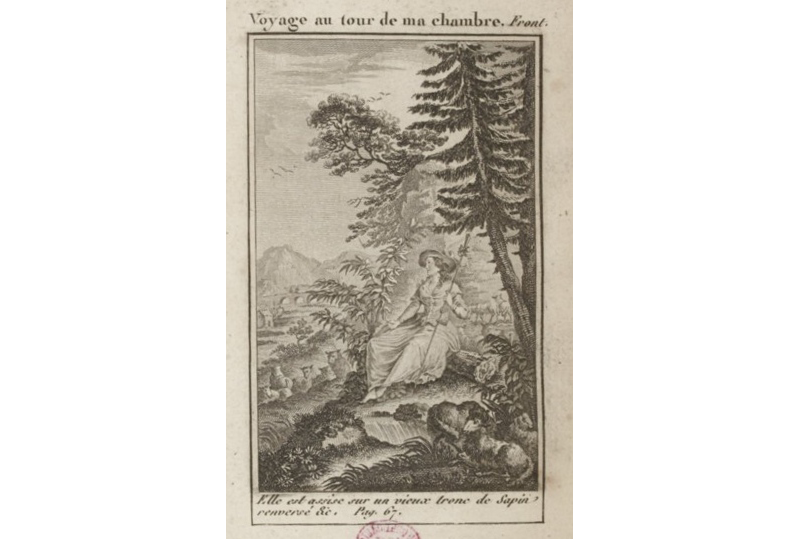

At the end of the 18th century, a Frenchman by the name of Xavier de Maistre had to undergo house arrest for dueling. He made the best of it and traveled about his room. He was inspired by the paintings, the books on the shelf, his servant, his dog, his lover. And he wrote a book about it. Voyage Around My Room is a stroll across a room where in fact nothing really happens. Nevertheless, he developed a real taste for it. Among the praise of his “voyage” was the following (for the infirm, in this case): “They need not fear the inclemency of the elements or the seasons. As for the faint of heart, they will be safe from bandits, and need not fear encountering any precipices or holes in the road. Thousands of people who, before me, had never dared to travel, and others who had been unable, and still others who had never dreamed of it, will now, after my example, undertake to do so.”

This extraordinary trip of the “sedentary traveler” took a full 42 days and cost him nothing. While thinking, dreaming, reading, and remembering he even learned to see the world with new eyes. He complemented it later with a “expedition nocturne autour de ma chambre,” an expedition of his room undertaken at night. De Maistre even went so far as to laugh about the travelers who had seen Paris or Rome.

More than two hundred years after this account was written, we don’t how many readers actually followed de Maistre’s noble example; but even today, does it really sound so ridiculous?

His obsession with little details seems so familiar. These are the same kinds of high points that “ordinary” travelers experience anyway. It is not usually the glorious monuments (with a few exceptions, such as St. Peter’s Basilica) that we remember, but for the most part oddities, involuntary detours, misunderstandings, smells (and stenches), tastes, sounds, and colors; the more-or-less welcome surprises and, yes, the encounters. I was lucky to have caught a glimpse of Arthur C. Clarke on the southern tip of Sri Lanka as he was followed by a frenzied group of Japanese fans. I arrived in Tangiers too late to meet Paul Bowles, but I happened to shake hands with Pierre Bergé, Yves Saint Laurent’s partner (and a reason for the local guide to ask me for an extra tip). From other trips undertaken a couple of decades ago, I remember barely more than a few images: a night spent half-awake in a shabby hotel in the harbor district of Marseille. A gun pointed at me at night somewhere in Wyoming, not being aware of the risk you take when sleeping outside on a hot night. A monkey defecating while I was passing underneath a tree in India.. Am I “well-traveled”? I don’t think so, but what does this mean anyway in today’s world?

Then there are the things that don’t run smoothly while traveling. Among my favorites is a little essay by Natalia Ginzburg, titled “Clueless travelers,” in which the Italian writer describes people who just can’t travel. “Once they arrive in the foreign city, these clueless travelers take refuge in a hotel, this hotel not signifying a point from which to set out and see the city, but truly a refuge in which to hide and cower, the ways cats or mice cower under a sofa.” Still there must be a reason for this particular type of traveler: “Not that those who can’t travel may not find some subtle pleasure in their rare trips, but it is a pleasure so blanketed in mist that they don’t even notice it; only later, in retrospect, do they glimpse its shadow.” Is such a distant realization really the hardship that these people endure? I don’t know.

Why do we travel anyway? Is it just a habit? Do we do it because of convention? Of course the answers are as manifold as the travelers. “Loafing around in a new world is the most absorbing occupation,” wrote the Swiss author Nicolas Bouvier. The world that he described in The Way of the World was far from being a safe place, and the sun wasn’t his only mortal enemy. In 1953, he traveled with a friend from Switzerland to the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan: not flying, but driving overland in a little Fiat. They were not spoiled youngsters — they had to teach French in Tehran to get by and be able to continue their trip to Kabul where they met “the little Western colony” — expats from Denmark, England, France, and Germany. Even though they encountered difficult situations, their 19-month trip was by no means terrible, and, while they sometimes tested cultural limits, they weren’t looking for perilous excitement. Maybe Bouvier, whom it took ten years to write the book, was the Jack Kerouac of Switzerland or the Bruce Chatwin of his time.

Perusing older classics of travel writing such as this one, my feeling is that traveling has become much more complicated, in part also because it has become much easier to get to even the remotest of places. It sounds like a paradox, but it’s not. With the help of the internet, we can get the most up-to-date information on the place we intend to visit just before we arrive there. And because people travel so much, we may be met or confronted with certain expectations. It requires an almost conscious effort to let go and skip something here and there. On the other hand, it’s an unfortunate fact that there are fewer and fewer countries we can set foot in without having second thoughts crossing our minds. Are we more aware of geopolitical factors? Of crimes and attacks a few minutes after they have happened? Only recently, the US Department of State even issued a travel alert for Europe. Looking back, it’s difficult to believe how little I knew before I went to certain places. 20 years ago, I squeezed myself into the back row of an overland bus from Sharm El-Sheikh at the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula to Cairo and back. Today it would be risky if not impossible to make this trip because of human traffickers and Islamic State fighters in the Sinai area, where the official line is to “advise against all but essential travel.”

Fear and uncertainty are reshaping the landscape of travel. Is the utopian potential of world-wide travel gone? Maybe. I still take much pleasure in the idea of being able to go to a different city, get to know it and learn the language, just as if it were a new home where I may settle. It’s probably driven by a longing to find a place where I “really” belong. André Aciman goes a step further. In his essay “The Contrafactual Traveler”, he writes that he is not even interested in the strange and unfamiliar: “I can’t wait to land on things I’ve known before.” This is related to his identity as an exile from Alexandria. For him, “home” is always elsewhere.

For Paul Theroux, one of the grand doyens of travel writing, something seems to have changed: His passion for the foreign appears to have been lost, if only partly so. During a trip traveling north from Cape Town, the ubiquitous poverty and corruption overwhelmed him. And far worse: Three men he meets on the way get killed. “My lifelong idea of supreme happiness was being a passenger on a train rattling through the night to a distant place unknown to me. But I thought, Not this time. I had no desire to board the train”, he writes in The Last Train to Zona Verde, his last book about Africa, a continent he loves. His trip thus ends before he passes into the Congo, half-way to Timbuktu, Mali, his original destination.

Are we able to stay at home and explore the meaning of the things around us, at least until the world has gotten a little more “normal” again? Pierre Bayard, a professor and psychoanalyst in Paris, and a kindred colleague of de Maistre — a de Maistre 2.0, so to speak — may provide us with some additional requisite know-how on how to not lose face and even be comfortable with staying at home. In How to Talk About Places You’ve Never Been: On the Importance of Armchair Travel, he dissects the reports of the likes of Marco Polo, Jules Verne, Karl May, on minute details of geographies they had never visited, to tell the reader they were wrong. He exposes the alternative reality they unfolded, but he doesn’t blame them: “Ill-equipped to defend itself against wild animals, inclement weather or illness, the human body is clearly not made for leaving its usual habitat and even less so for traveling to lands far removed from those where God intended us to live.” And: “We know from Freud and the works of other psychiatrists who have studied various travelers’ syndromes that traveling a long way from home is not only liable to provoke psychiatric problems: it can also drive you mad.” •

Feature image courtesy of Shannon Sands. Images courtesy of madame.furie via Flickr (Creative Commons) and Sapcal22, TigH, and Teddy219410 via Wikimedia Commons