History has remembered the Spanish-American conflict as a “splendid little war.” Between April and August 1898, over 72,000 American soldiers, sailors, and Marines steamrolled the larger forces of the decaying Spanish Empire in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. Former Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, who had given up his position in the McKinley administration in order to create the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry (better known as the Rough Riders), became an all-American hero after the war. More importantly, America’s victories at San Juan Hill, Santiago, and Manila Bay showed the world that Washington had now entered into the age of empires.

The Spanish-American War is notable because it conclusively proved that the media can concoct a war without much evidence. The “gay ’90s” in America belonged to the press barons, otherwise known as the purveyors of “yellow journalism.” Competitors William Randolph Hearst (later portrayed as the character Charles Foster Kane in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane) and Joseph Pulitzer fed war fever prior to the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana harbor by writing sanguinary and exaggerated stories about Spanish atrocities against the innocent and helpless Cubans. While thousands of Cubans really did suffer in concentration camps, Hearst and Pulitzer often filled their pages with imaginary Spanish intrigues against the United States and American businessmen in Cuba. As a gross indication of the press’s power, one apocryphal story claims that illustrator Frederic Remington received a telegram from Hearst while covering the Cuban rebellion: “You furnish the pictures and I will furnish the war.”

Across the Atlantic, European journalists also shed their pretensions to impartiality in order to fuel war fever. In 1898, during the middle of the Spanish-American War, newspaper editors in in London and Paris almost started a war between the British and French empires when the two sides met at Fashoda in southern Sudan. The two great powers claimed the town as their own. When neither showed signs of acquiescing to the other, British and French patriots took to the streets in order to argue for war. Many held up damning headlines from their favorite daily newspapers. Hardly anyone in either country, journalist or not, could find Fashoda on a map, but most agreed that it was worth dying for. The alliance between imperial geopolitics and the news media proved to be an intoxicating brew.

The supposedly straight press in America and Europe had competition when it came to trumpeting jingoism between 1897 and 1898. Fiction, rather than sensationalist journalism with fictional elements, played an important role in preparing Americans for an all-out conflagration with a European power. Ironically, one of the main examples of war-fever fiction came from unlicensed reprints of an anti-imperialist classic.

H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds remains today one of the author’s most recognizable works. Thanks to several film adaptations and one infamous radio adaptation by Orson Welles, the average American can probably repeat the basic gist of the story — an army of predatory Martians lands on Earth, lays waste to the entire world, then they all die off thanks to the tiny microbes in our atmosphere that we have long been acclimated to. In his original novel, Wells ends on a dour note, suggesting that there is nothing stopping the Martians from returning.

At present the planet Mars is in conjunction, but with every return to opposition I, for one, anticipate a renewal of their adventure. In any case, we should be prepared. It seems to me that it should be possible to define the position of the gun from which the shots are discharged, to keep a sustained watch upon this part of the planet, and to anticipate the arrival of the next attack.

Whether or not this second attack comes, Wells’s everyman narrative explains that humanity “must be greatly modified by these events.” Humanity can no longer look upon Earth as a secure refuge, and humans must also understand that the “commonwealth of mankind” necessitates collective action regardless of national borders. For Wells, a lifelong socialist who wrote his “scientific romances” (Wells’s own term for science fiction) in order to argue for global governance, a fictional Martian attack showed the real need for a new, more “scientific” structuring human society.

The War of the Worlds has long been read as a British novel about the experiences of people conquered by the British. The Martians treat the rural and urban denizens of imperial England the way that the British military treated Indians, Irish Catholics, South African Boers, and a whole host of other peoples. While, in hindsight, this anti-war, anti-colonialism message seems clear, it was not terribly clear to popular writers during the fin-de-siecle. Even today, despite Wells’s anti-imperialist intentions, The War of the Worlds is best remembered as an action-packed potboiler that combines realism with advanced weaponry. Its political points are often missed or downplayed.

In both Britain and America, unauthorized versions of the story were serialized in popular newspapers. These versions of Wells’s story proved more popular than the original in America, and much of this had to do with the local appeal of the material. For instance, as Steven Mollmann notes in “The War of the Worlds in the Boston Post and the Rise of American Imperialism,” Fighters from Mars, an unauthorized adaptation that began appearing in the New York Evening Journal in December 1897, shows the Martians landing in New Jersey and making their way towards New York City. In a similar vein, Fighters From Mars, or The War of the Worlds in and Near Boston ran from January 9th to February 3rd, 1898. This version of Wells’s story features Martians recreating the British march on Boston during the early stages of the Revolutionary War, thus tying together two different ages of imperial warfare.

These American adaptations of the story viewed the Martian invasion from a completely different lens. Rather than use the Martians as stand-in imperialists, the heroes of these adaptations became the mouthpieces for American imperialism. Edison’s Conquest of Mars, one of the more outlandish adaptations of Wells’s story, features the famous American inventor as an intergalactic warlord who uses a Martian-created “disintergrator” in order to lead a Earthly conquest of the red planet. The novel’s author, Garrett P. Serviss, wrote that the “United States naturally took the lead, and their leadership was never for a moment questioned abroad.” These words came at a time when not only was the American economy in the process of overtaking its British and German rivals, but, as noted by David Seed in “The Course of Empire: A Survey of the Imperial Theme in Early Anglophone Science Fiction,” they also formed part of a broader historical moment when the Republican Party was openly bragging about America’s civilizing mission for “humanity” in the Caribbean and Southeast Asia.

Many decades later, another important element about War of the Worlds adaptations appeared. On October 30, 1938, Orson Welles performed a dramatic update on Wells’s original story that involved Martians touching down on a small farm in New Jersey. This version more or less revised the print adaptation first serialized in the New York Evening Journal in 1898. And like the Boston Post’s version of the novel, radio listeners in 1938 reacted as if the invasion was true. This conceit, namely that there is a bit of believability in Wells’s extraterrestrial tale, comes, in part, from the very visceral fear of conquest. Furthermore, Wells drew inspiration from a older source of literature — the military invasion story.

George Tomkyns Chesney’s The Battle of Dorking (1871) is often considered the first of such sci-fi tales. In this novel, a future Britain is invaded and decimated by a foreign power (a thinly-veiled Germany). Thanks to so-called “fatal engines” (a type of high-tech, super-weapon), Britain’s enemies outclass the Royal Navy on the high seas. The British Empire is cut up, and the Anglo-Saxon race is left with nothing more than civil war.

Chesney intended for his book to be a criticism of the poor state of Britain’s armed forces. As a member of the Royal Engineers, he certainly had a stake in such matters. Chesney’s didactic approach would be copied by other authors, including William Le Queux, whose The Invasion of 1910 describes a successful German invasion of England. In that novel, Le Queux gives voice to British xenophobia by portraying all German immigrants, from lowly waiters in London to railroad workers in the north, as reserve soldiers and saboteurs for the Imperial German Army. This fiction proved far more popular with the British reading public than Wells’s work, and there is an argument to be made that many readers may have consumed The War of the Worlds as if it were another piece of pulp.

Such yarns were not exclusive to Great Britain. Cleveland Moffett’s 1916 novel The Conquest of America is about the German destruction of the Panama Canal, followed up by an amphibious landing in New York. At the apex of the novel’s action, the Germans destroy the Woolworth Building, then the largest commercial edifice in the “Big Apple.”

Kenneth Mackay’s The Yellow Wave is also a perfect example of how these alarmist tracts about possible military invasions also overlapped with prominent “racialist” theories. In Mackay’s novel, Australia is left undefended by London, and thus falls prey to a Russo-Chinese invasion. Like other “yellow peril” tales, Mackay’s novel envisions hordes of Asian soldiers and laborers flooding Australia until the country’s founding European stock is completely subsumed. Even Jack London was prone to such thoughts, as 1910’s “The Unparalleled Invasion” shows.

Back in 1898, the unlicensed adaptations in the New York Evening Journal and the Boston Post warned American readers about the possibilities of a foreign invasion of the Northeast. Not long after the serialization of The Fighters from Mars in the Boston Post, the newspaper published an article entitled “Defense of Boston in Event of War.” This article detailed what would happen if the United States declared war on Spain. For Bostonians, the Post theorized that their fair city would be targeted by the Spanish warship Pelayo. However, similar to what happened during the denouement of the The Fighters from Mars, the editors of the Post told its audience that the U.S.S. Indiana was superior to the flagship of Spain’s Atlantic Fleet. Such enthusiasm for war animates both the New York and Boston adaptations of The War of the Worlds. Both novels were sold to their readers as thrilling action stories about the latest advances in military technology, and both stories lionized the United States as the world’s most important country.

The Boston Post’s version of The Fighters from Mars makes explicit that the Martians decided to invade the United States because destroying America’s cultural and historical heritage would be the ultimate coup of interstellar politics. As Mollmann notes in his article, The Fighters from Mars that was devoured by the Boston public reads at times like a travel brochure describing the historic sites of Massachusetts.

Leaving the Common the Martian quickly passed up Monument street, blazing woods and burning houses marking its path. Turning to the left he came to the bank of the sluggish Concord River, and through the trees he saw the monument which marks the spot where the first English soldier fell when Pitcairn’s troops stood at one end of the famous North bridge and the American troops, advancing on the other side of the bridge, fired “the shot which was heard around the world.” Such objects seemed to excite the suspicion of the Martian.

The Fighters from Mars displays, through Martian violence on Lexington, Concord, and Boston, the vim and vigor of a new nation about to set course on global expansion. After all, the Martians would not pick just any backwater to begin their conquest; only historic Boston and the United States would do. In the New York Evening Journal, New York City, the largest city in the United States and the country’s financial heart, provided ground zero for the Martian invasion. Both stories end in American triumph, and, tellingly, both suggest that the next move for the U.S. is a conquest of Mars led by a technologically advanced American army. There is no Wells-like fatalism in these stories; they are full-throated hurrahs for American imperialism. With the explosion of the Maine (whose deployment to Cuba was supported by the editors of the Post on January 14, 1898), the “yellow press” and invasion-story writers got their wish.

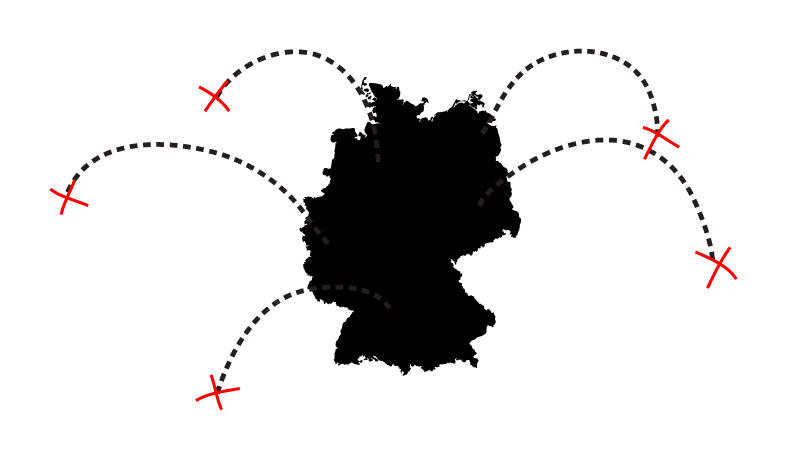

There is an interesting coda to all of this. There really was a planned invasion of the United States and some of its territories, but the plot did not emanate from Spain or Mars. In 2011, German scholar Volker Schult translated and published in the Philippine Quarterly of Culture & Society a series of letters from the German Colonial Society, a powerful propaganda outfit dedicated to promoting German colonialism. In 1898, society member Professor Claus sent a letter to Duke Johann Albrecht of Mecklenburg, the organization’s president, detailing the reasons why Germany should try to take parts of the Philippines away from America. The island of Mindoro was of particular interest.

Only the island of Mindoro south of Luzon has such a location. Mindoro could become a way station to China and Japan and also a mediator of German trade with these countries . . . The fact that the island is still almost completely independent and has to be conquered and exploited yet, many also reduce the value of Mindoro in the Yankees’ eyes. We German who have pacified rather fast and easily much larger and less accessible areas of East and Southwest Africa would certainly not shrink back from acquiring an easily accessible island of 200 square miles.

Berlin’s interest in the Philippines went further than mere talk, too. The big dreams of the German Colonial Society led Kaiser Wilhelm II to send Vice-Admiral Otto von Diederichs to Manila during American Admiral George Dewey’s successful campaign against Spain’s ill-prepared Asian fleet. Von Diederichs’s squadron was told to remain in the Philippines no matter what, but when Admiral Dewey threatened war with Germany, the German flagship Kaiser left the archipelago on August 21, 1898.

A far more audacious German war plan percolated in Berlin between 1897 and 1898. Kaiser Wilhelm’s first plan, which was entrusted to naval officer Eberhard von Mantey, envisioned the German Navy attacking American ships anchored at Norfolk and Hampton Roads in Virginia. Later, during the Spanish-American War, Mantey revised the plan to argue for an amphibious landing at Cape Cod. From there, German Marines would march on New York City. Imperial German designs on hitting the American mainland would last all the way up until 1917, when German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann proposed dividing the American Southwest and West Coast up between Mexico and Japan. The infamous “Zimmermann Telegram” helped to push President Woodrow Wilson and the American public closer to war — a war that would completely sever Kaiser Wilhelm II and the Hohenzollern monarchy from German history.

As far-fetched as actual German military invasions of America might sound, on the morning of July 21, 1918, German submarine U-156 captained by Richard Feldt fired on the town of Orleans, Massachusetts. The submarine sunk a tugboat near Nauset, but otherwise failed to induce any casualties. Despite this, American newspapers published dire articles about more enemy submarines patrolling the Eastern seaboard. Some even worried that a German floatilla could strike New York or Boston at any time. Old fears from the days of the fictional Martian invasion were revived once again.

There seems to be something primal about The War of the Worlds, whether in its original form or its many adaptations. Wells’s story combined the language of real-world reporting with fiction at a time when such distinctions were blurry anyways thanks to “yellow journalism.” In the same year that The War of the Worlds began serialization in Great Britain and the U.S., newspaper magnates like Hearst and Pulitzer successfully used sensationalism in order to get the United States involved in the affairs of the Spanish Empire. The Spanish-American War finally drove Madrid out of Latin America, but in the following years, the United States government found itself as the new imperial power of the hemisphere. Between 1900 and 1934, U.S. soldiers, Marines, and sailors would be deployed to the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, Panama, Haiti, Nicaragua, Mexico, and Cuba in order to put down rebellions, collect loans, and to spread “good governance.” Much of this would not have been possible without bad journalism and a few nationalist novel adaptations in 1898.

Ironically, the very same papers that rushed America into war in 1898 quickly turned on U.S. “pacification” efforts in the Philippines after letters home revealed that U.S. troops regularly used the “water cure” in order to pull information out of suspected insurgents. The outrage may have been real at first, but the Hearst and Pulitzer papers used these accusations as a cudgel to try and bring down President Theodore Roosevelt, a man suspected of being a major threat to big business in America.

The power of these news syndicates did not wane until the 1970s, when post-Watergate cynicism got ahold of the American public. Many began to see journalists as political hacks and fiction writers. The murkiness of the distinction between fact and fiction has not changed, and subsequent events, from the Gulf of Tonkin to Saddam Hussein’s WMDs, have further convinced Americans that journalism is often just a dishonest brand of fiction.

The seeds of public doubt began way back before the turn of the century. In a weird way, a string of poor adaptations of science fiction classic primed an excited audience for less-than-true depictions of warfare, colonial conquest, and national prestige. These stories provide not only a glimpse into the days when America first began acting like a great European power, but also into the original sin of journalism in America. It has always been about selling something, and the current defense of journalistic objectivity rings hollow given the past crimes of paid scribbles. •

All images created by Emily Anderson.