The Metropolitan Museum Breuer on 75th Street and Madison Avenue (the former site of the Whitney Museum now relocated to hip new quarters downtown) currently features an exhibition that seems perfectly suited to an outpost of the Met. What should an outpost do, after all, if not reframe and critique the masterworks of the established space? The exhibition now on display, entitled Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, does this with intelligence and panache.

The exhibit includes about 200 works, from the 15th century through the present, that are loosely defined as “unfinished.” I say loosely because the term can mean at least three things: the work was left unfinished due to the exigencies of the artist’s life (a more pressing commission, an illness, or death); it was abandoned out of dissatisfaction or incapacity; or it was intentionally left to look incomplete as the expression of a non finito esthetic. But these categories don’t help much. Why a work was left unfinished or whether, in fact, it is unfinished can be ambiguous or subjective. The curators, thankfully, admit this, even as they postulate what the artist may have intended.

The most interesting works in the exhibition are on the third floor, but the show continues on the fourth to encompass abstraction and conceptual art. This extension seems forced, even undermining of the power of what came before. But I will return to that.

Overall, the show is a visual delight and a philosophical revelation. I found I often liked the unfinished works on display better than the finished ones that I knew by these artists. Finish has obvious value from the point of view of resale and comprehensibility, but is it as esthetically pleasing or evocative? One could argue that a finished work is often over-finished, and that knowing when to stop is rarer than generally thought.

No one understood this better than that most revered of artists, Leonardo da Vinci. Known for not completing things, Leonardo has been labeled a chronically dissatisfied, restless artist. But could the psychological diagnosis mask an esthetic one — a conviction that leaving a work in limbo might serve it better than bringing it to fruition? We have the portrait of Ginevra de Benci, The Virgin of the Rocks, Lady with the Ermine, and, of course, the Mona Lisa, among a smattering of finished works by this master. But so much of what we revere about da Vinci is fragmentary: The Adoration of the Magi and Jerome in the Wilderness are unfinished, and there are the beautiful sketches and inchoate ideas in his notebooks that we associate with his genius. This show features an exquisite work on pine of a young woman’s head with disheveled hair, entitled La Scapigliata. It may be unfinished or it may simply be the artist’s way of suggesting the incompleteness of the lady’s toilette — a visual rendering of what the poet Robert Herrick’s called “delight in disorder.” After viewing La Scapigliata, one may even entertain the heretical notion that the Mona Lisa is over-finished.

The same sense of non finito pleasure accompanies a work, the earliest in the exhibition, by Jan Van Eyck — a 1437 rendering of St. Barbara. It is a brushstroke drawing on an oak panel with a chalk background. There appears to be some color added, but it is muted and uneven. The work has a breathtaking delicacy, as though it is evaporating as the artist made it.

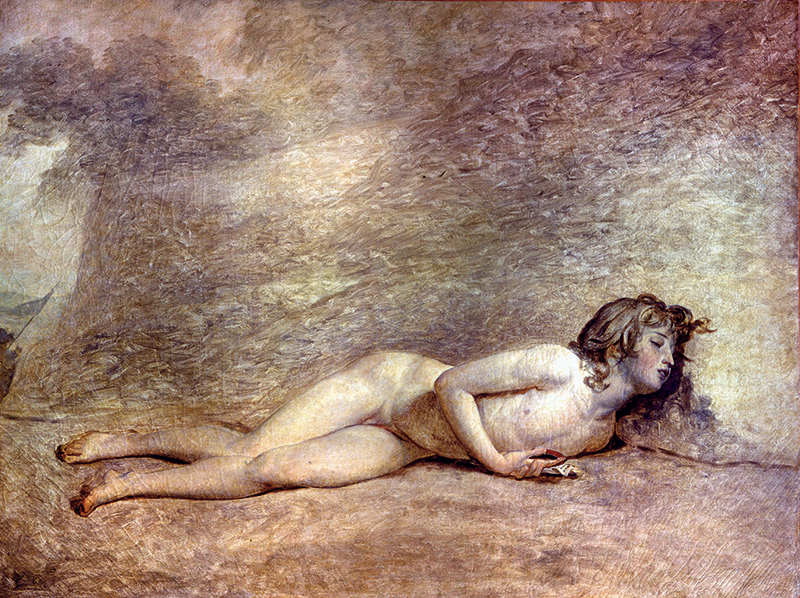

Titian is another monumental figure for whom the issue of finish seems connected to larger esthetic questions. Late Titian was famously unwilling to belabor the obvious — the smaller details of a work didn’t matter to him so much as its dynamism and atmosphere. The show includes the powerful Flaying of Marsyas: the satyr Marsyas, hung upside down, has his skin being peeled away as punishment for having lost a musical contest to Apollo. The muddiness of portions of the canvas make it seem both chaotic and mysterious, poised between pagan rite and Christian allegory.

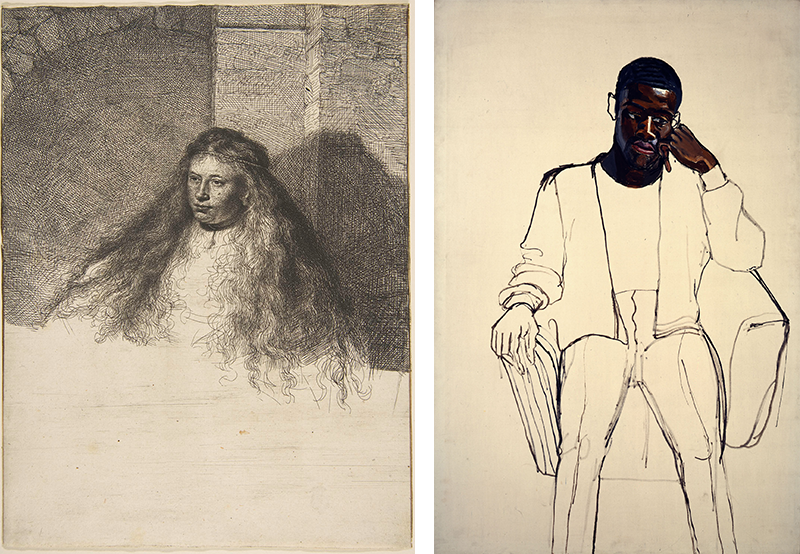

One of the most arresting works in the exhibit is a 1775 painting by Raphael Mengs of a woman holding a dog. Much of the work is realistically finished in bright color and detail, with the exception of the woman’s face and her dog, which exist as outlined spaces with blank interiors. The painting looks like a work by Magritte. A similarly surreal effect is relayed by the 16th-century Holy Family with St. John the Baptist by Perino del Vagas in which the infant at the center is finished but the family around him remains a mass of spidery lines on a mottled white background. It is as though the baby is being held by vellum cut-outs or fragments of ancient statuary. Both of these paintings tell us things about their artists’ technique, but they also dramatize the fragility of realistic representation. Excise a few details and one is plunged into dreamscape.

Among my favorite canvases in the show are by J.M.W. Turner, done in the last decade of his life. I have never been a fan of Turner’s blurry depictions of spindly ships and disorderly ports. But I loved these late works. After seeing them, I felt he had finally given into his true interest in atmospheric flux after having hung on, for too long, to realistic representation. Whether finished or not, these paintings seem to be where he had been heading all along.

As the exhibit moves into the modern period on the fourth floor, the unfinished esthetic begins to lose some of its charm. I put this down to a new level of self-consciousness. The German philosopher Friedrich Schiller made the distinction between the naïvete of classic work and the sentimentality of Romantic work — one being spontaneous and natural, the other self-conscious and artificial. Schiller was writing before modernism, but it can be said that modern art is sentimental in its self-consciousness: it elevates the artist into a heroic maker.

We see this with Picasso. In the works represented, the unfinished esthetic seems clearly deliberate — an ironical commentary on the artistic process. Other, more contemporary artists, like Alice Neel to Andy Warhol, give a similar impression.

Work by such abstract artists as Barnett Newman, Jasper Johns, and Jackson Pollock don’t seem to belong in the show at all. As the curators note, they are concerned with the infinite, which seems like a stretch to include under the category of the unfinished. As for conceptual art, the focus is on paradoxes of space and time, and the whole issue of finish seems beside the point.

Another approach to the unfinished in art, not touched upon in this exhibit, is from the direction of its future — its ability to be damaged or changed over time. Many Old Master paintings have been the subject of controversy in this regard. The chiaroscuro of dinge can be evocative, and when the bright colors of the original are restored the effect can seem crass and displeasing. Many complained of this after the restoration of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling. I had this experience some years ago when my husband unearthed a dirty painting of the Annunciation in a junk shop. Enamored of its possibilities, he paid a small fortune to have it restored, only to reveal a second-rate 19th-century copy of a minor Old Master. Better to have left the imagined 17th-century Venetian masterwork beneath the grime.

When I think more on the subject of the unfinished, I realize that completing a work, whether of art or literature, always involves a diminishment. Wordsworth referred to poetry as “powerful feeling recollected in tranquility.” William Butler Yeats took a more bitter view of this exchange: “Bodily decrepitude is wisdom/Young we loved each other and were ignorant.” In this context, the artist who fails to finish his work can be said to be grappling more directly with life.

On another front, I often find myself taken with a trailer for a movie or a review of a book more than with the movie or the book itself. The fragment — that summarizes or distills the larger whole — may seem greater because it can ignore chronology and logic. It can sketch without filling in; hint and draw back.

Ironically, an unfinished book or movie strikes me as less evocative than a painting, perhaps because these media generally require cutting and pruning to be complete. An unfinished work of literature or film can therefore seem over-finished when it is unfinished; i.e. unedited. Think of what Maxwell Perkins had to do with Thomas Wolf and Gordon Lish with Raymond Carver; think of the tedium of over-budget, unfinished films by Erich von Stroheim and Orson Welles.

But to see great painters leave blanks in their work is to get a titillating insight into their greatness. These are the places where they could or would not go, where we can project something even greater than what they represented in the materiality of paint. These are spaces that our own imaginations can occupy. •

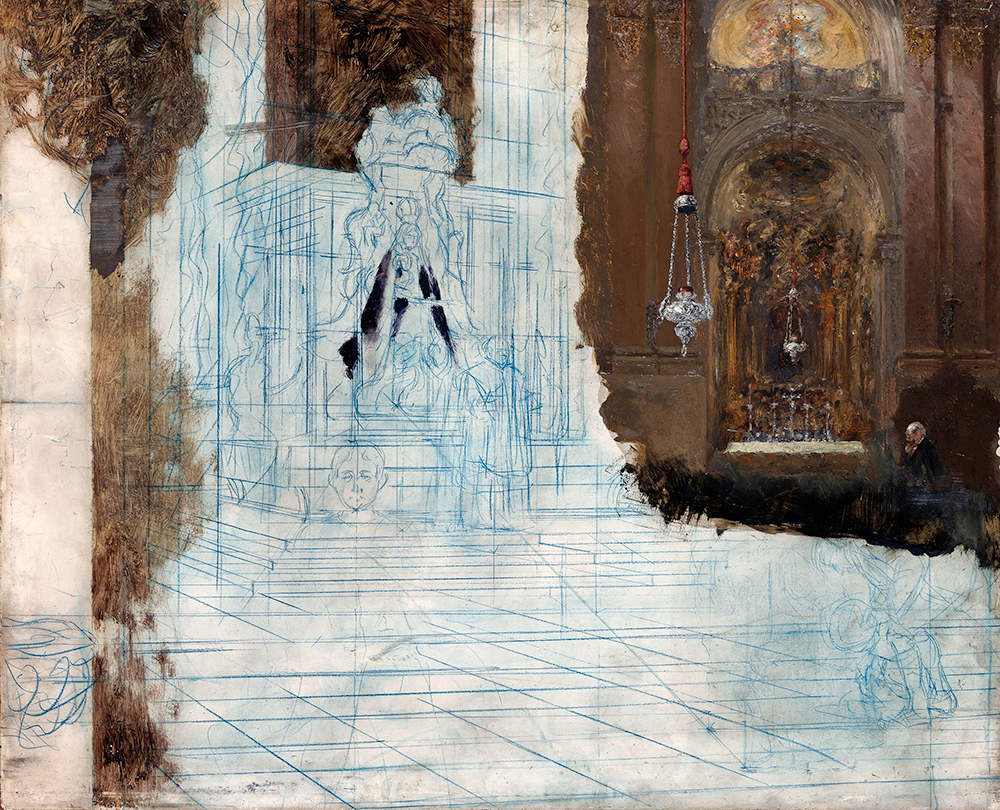

Feature image: Adolph Menzel, Altar in a Baroque Church (ca. 1880–1890). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. All images courtesy of The Met Breuer exhibit Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible.