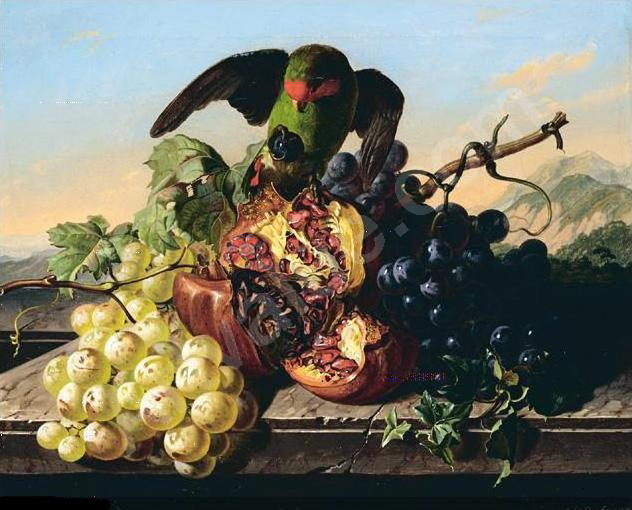

We expect fruit to not make it too difficult for us to have access to its inner parts. Many varieties fulfill this expectation, while some put up a fight. Quinces, for example, have to be cooked before eating because otherwise their flesh is too hard. Beneath the tough skin of the pomegranate hides a complex center that seems bound to mysterious laws: Inside are chambers divided by membranes, which in turn are filled with hundreds of tiny, angular sacs of juice that burst easily to the touch, each of which contains a pip. You can squeeze a pomegranate or cut it into pieces and pull the seeds out with your teeth. After a bit of practice, you get the hang of it. Cutting one of these fruits open requires some caution, however, as the juice is notorious for causing stubborn stains. To a greater or lesser extent, the fruit has a tart taste, but it is not very aromatic and its flavor is short-lived; the small pips are resinously bitter. The hermaphroditic pomegranate blossom doesn’t even have a scent. This mysterious “berry” seldom brings on love at first sight, but it’s worth taking a closer look.

The weak points of this fruit – if you can call them that – haven’t diminished its attraction. It caused a welling of “desire and anticipation of foreignness and southernness, and the allure of great journeys” in the German poet Rilke, according to a letter he wrote to his wife Clara. All over the world, there are stories linked to this astounding fruit; its blood-red color even inspired the surrealist Russian-Armenian film The Color of the Pomegranate.

Pomegranates – Punica granatum – grow hanging like Chinese lanterns from spindly branches. Botanists find it hard to give the almost spherical fruit a morphological classification. “With its leathery rind, the pomegranate resembles a citrus fruit whilst its calyx, which so prominently adorns its apex, is indeed reminiscent of an apple,” explains Wolfgang Stuppy, seed specialist at the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. However, when it comes to the edible part, the pomegranate has nothing in common with either an orange or an apple. What we eat when indulging in this legendary fruit are, in fact, the red and juicy seed coats that cover each individual pip.

Why Punica granatum in the first place? Punica can be traced back to the Phoenicians, who allegedly popularized the fruit throughout the Roman Empire. Back then it was known as Mala punica, or the “Punic apple.” The Latin granatus means “granular” or “rich in seeds.” A small lethal bomb filled with gunpowder might be called a “hand grenade,” and the fruit is likely to explode too, scattering its seeds all around (however, there exist non-cracking types). Mineral garnets, when split open, also have a clear resemblance to the fruit. And it’s likely that the Moors introduced the fruit to Western Europe via the Andalusian city of Granada.

The pomegranate belongs to the family of Lythraceae, which places it in the illustrious company of the henna shrub, Brazilian rosewood, and water chestnut, although this may not be immediately obvious to the non-botanist. But there is also a mystery that surrounds it. Besides the familiar variety, of which exist a total of 500 breeds, there is a second variety that grows off the Horn of Africa on the Yemen-governed island of Socotra (difficult to reach nowadays due to military unrest in the region). It has an exceptionally bitter taste and it is said to be eaten only by local shepherds as a last resort. The nature of the relationship between the two varieties — whether or not our pomegranate derives from this exotic island species (as its name Punica suggests) – is not clear, as no relevant studies have been made to date. Some botanists regard both varieties as related species that originated from a common, extinct ancestor, while others believe the one growing on Socotra is a dead-end in the evolution of this plant’s family.

The pomegranate must have other properties to have caught people’s imaginations for centuries. Unlike the potato, tea, sugar, or cotton, it hasn’t determined the course of world events: Its influence has been subtler. Rich associations run like a common theme through the cultures of antiquity. It is even possible that Adam and Eve’s forbidden fruit came from a pomegranate tree. The fruit’s large number of seeds earmarked the pomegranate’s destiny as a fertility symbol. It can be found as a holy plant among the ancient Egyptians and in Judaism. Here, the perfect pomegranate contains exactly 613 seeds, which corresponds to the number of commandments in the Torah. In ancient Greek reliefs, the pomegranate is sometimes a divine attribute, sometimes a sacrifice for the living, and, at other times, a gift for the heroized dead. Sometimes the fruit appears on equal footing with an egg, a blossom, or a cockerel. A semi-clad Aphrodite often carries a long scepter crowned by a pomegranate. Its unmistakable form has been modified many times, occasionally complemented by ornaments and rediscovered in the form of bottles of oil, vessels of ointments, glass vases, and gold pendants. Its characteristic calyx supposedly inspired King Solomon’s crown, and then those of the European monarchs. In ancient Rome, young women bedecked themselves with wreaths made of pomegranate leaves in the hope of being blessed with fertility. In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, a lark sings from the branches of a pomegranate tree. In some cultures, especially in Iran, it features in celebrations to this day, such as weddings, where anaar is dropped to the floor: They say the burst fruit brings fortune in engendering children.

Humans have only cultivated pomegranate trees for the past 5,000 years or so, and besides olives, figs, dates, and grapes, they count among the oldest crop fruit in the world, predated only by a few types of grain. This makes the fruit analogous to the horseshoe crab of the flora world. Rind scraps found in Jericho date back to the Bronze Age. The pomegranate was never farmed on the same scope as citrus fruits, cherries, pears, or apples, all of which came later, and that’s why its modern-day shape isn’t dissimilar from its original wild form, which still grows in northeastern Turkey, Iran, Albania, and Montenegro.

Ripened over the summer, the fruit was ideal for storing or being transported by nomads over long distances and eaten as refreshment. Later it found its way to India and China and was brought by the Spanish to the Americas. In Japan, it even exists in bonsai form. In the USA, varieties now thrive with names like “Wonderful” (which tastes of wine), “Utah Sweet” (especially sweet), and “Francis” (large, sweet, and doesn’t burst easily). Lighter-colored seeds are usually sweeter than dark red ones because they contain fewer organic acids. In California in particular, growers try to optimize the fruit even further, not only in taste but also in content; they talk of elite breeds.

The bush or tree, which can grow up to five meters, is not fond of high temperatures or humidity; on the other hand, it is sensitive to frost and tolerates almost every soil type. It can even thrive at high latitudes, but then only as a potted plant because it is not winter-hardy.

This attractive fruit has been showered with positive attributes. As far back as Hippocrates, a woman suffering from stomach complaints would be recommended to take grains of pearl barley sprinkled with pomegranate juice. The juice contains a variety of vitamins and minerals such as phosphorous and potassium. What’s especially interesting is the high content of polyphenols and flavonoids, in contrast with the surprisingly low vitamin C and calorie contents. The antioxidant effect of its juice is much higher than that of red wine or green tea.

The number of studies into its chemical makeup has sharply increased over the past two decades and the reports do not let up on the positive effects of the red juice, the tannin-rich rind, the tree bark, and the blossoms. About ten years ago, American researchers caused a stir with the hypothesis that the juice contained HIV entry inhibitors in particularly high concentrations, which may prevent an infection caused by the virus. There are indications that pomegranate juice protects coronary vessels and supports blood circulation in the heart muscles; that it slows down the growth of prostate cancer cells; that it is effective in the treatment of diabetes and osteoporosis; and that it can inhibit microorganisms that cause tooth plaque. The astringent effect of blossom and rind extract supposedly aids tissue repair and is effective against hemorrhoids and throat infections. But despite all its rich symbolism, it is not effective in aiding fertility – in fact, doctors advise women not to eat pomegranates during pregnancy. These days, a striking number of herbal doctors, many of them at the National Research Centre on Pomegranate in Solapur, India, are investigating the effect of the plant’s components on humans. It is no coincidence that this research is taking place on the Indian subcontinent: The blossoms, bark, and roots have long been used in traditional Ayurvedic medicine to treat diarrhea and intestinal parasites.

The crimson fruit has even made political headlines: Last winter, a rumor circulated that the Islamic State had injected pomegranates with poison meant for Iraqi Kurds, which later proved to be untrue. In Afghanistan, the cultivation of the fruit has the potential to hold at bay an economic system founded on the cultivation of poppy for opium production. It is said that the Afghan pomegranate is the best in the world – although the Iranians and Turks make the same claim. The sticking points are production sites and logistics: How to get the fruit or juice to wealthy, health-conscious connoisseurs. Because the fruit ripens over summer but doesn’t mature once harvested, making storage possible for months on end, the chances are not that bad that solutions to these problems will be found. Pomegranates are harvested as soon as the rinds take on a light yellow color and make a metallic sound when tapped. There is a clear trend: Demand for this superfruit is growing and the thirst for the red juice, with all its alleged benefits, can barely be quenched.

In India the acidic, dried pips of the wild pomegranate are used as a spice that bears the beautiful name anardana. The viscous juice, thickened by boiling and fermented, is a popular ingredient in Turkish and Persian cuisine. There are marmalades, chutneys, wines, and grenadine syrups for cocktails. It is used as an extract in skin products. Whatever uses and findings have already been established for this multi-faceted and divine fruit, simply sprinkling it over salad as decoration is not a deserving use. •

Translated from the German by Lucy Renner Jones