The instructions are clear: After having sex, the man is to stay in bed while the woman should get up and run in a circle around the room three times and complete 10 deep knee bends after each lap. It apparently does not matter if the woman runs clockwise or counterclockwise, but running swiftly in a circle and breaking to do knee bends was, as late as 1928, prescribed as a form of birth control.

So was Coca-Cola. Rumored to be a spermicide as well as a refreshing beverage, it seems to have been frequently used as some sort of post-coital cleanser.

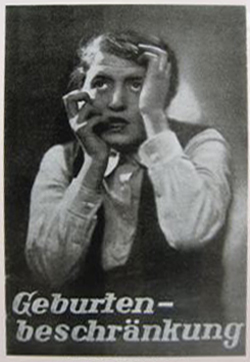

So there’s the deep-knee bends and the Coke trick as contraceptive folly. Add to that some anti-baby lipstick, pumps, sprays, clamps, one-quarter-inch thick condoms made from fish bladders, and a dizzying number of spiral intrauterine devices (that look oddly beautiful, fragile, and delicate, laid out in uniformed rows), which together create an amalgam of sexual factoids and implements — contraceptive information and misinformation — on display at the Vienna Museum of Contraception and Abortion.

Austria is a Catholic nation. Roadside shrines to Jesus and Mary dot the countryside, crucifixes top cafe doorways, town halls keep records of every Catholic so the Church can fetch an annual tax, and if the newborn baby’s name doesn’t fit with the Bible, the priest may come calling.

And so the presence of a pro-choice abortion museum settled on a street named for the Mother Mary in the capital city is as unexpected as a lederhosened farmhand waltzing at the Opera Ball.

The country may have been baptized Catholic, but it seeks salvation in sex. The pope and his prayers, versus Freud and the penis. Austria has bred about as many sexologists as the Church has saints, and while the Church is a deep cultural tradition here, spirituality is found between the sheets.

Austria has, more than any other nation, turned the issue of sex away from the Church, and toward science and humanity. Besides Freud’s Oedipal Complex and Penis Envy, nobleman Baron Richard von Krafft-Ebing, the world’s first sexologist, spent a good deal of the 1800s fastidiously studying the sexual habits of his countrymen, from homosexuality to fetishes to masochism (he actually coined the word). Austrian sex psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich was so sure that orgasms were a cure for neuroses and a guarantee of a healthy life that he went so far (too far, his peers said) as to invent an “orgone simulator,” under which patients sat to improve their health and vitality.

And Austrians are right smack at the top of the list when it comes to the sexually satisfied, according to a recent world survey by a condom company; they are also more likely to have one-night stands, and tend to start having sex at a younger age than their Western counterparts — all apparently without a whole lot of guilt and shame. In its Germanic pragmatism, this country has made sex about life, not about God, and in so doing, has rendered the Vatican impotent in controlling this little land.

This is why a village priest can keep an open secret about living with his girlfriend and kids; why prostitution is legal; why contraception is aggressively employed; and why the Austrian school system, which requires mandatory religion class, will also include a stop at the Museum of Contraception and Abortion during each school’s annual Vienna field trip.

The religious stigma around contraception has been neutralized because Austrians have made it clear that the Church is not to intervene in their sexual behavior. But the social taboo regarding abortion still exists. The motive behind the museum is to erase a moral issue by utilizing the same Germanic sensibility used to defuse the Church’s authority in the bedroom: To present abortion as a solution to a problem, not the problem itself; to turn the issue away from God and toward science and education.

The museum, across the hall from an abortion clinic (the doctor founded the museum), is comprised of two rooms. The first is the contraception room, the giggly one, where items such as packages of foot-long condoms are on display alongside the Coke story and other debunked “How-To’s.” This exhibit lays out the facts about the myths of contraception, displaying articles on inane practices and equipment that lay bare how alarmingly little anyone knew, until the late 20th century, about how to stop a baby from being made.

The museum, across the hall from an abortion clinic (the doctor founded the museum), is comprised of two rooms. The first is the contraception room, the giggly one, where items such as packages of foot-long condoms are on display alongside the Coke story and other debunked “How-To’s.” This exhibit lays out the facts about the myths of contraception, displaying articles on inane practices and equipment that lay bare how alarmingly little anyone knew, until the late 20th century, about how to stop a baby from being made.

The second room is the abortion room, the somber one, where newspaper clippings on botched abortions and murders of pregnant women are showcased.

But the museum may soon become a time capsule rather than the wake-up call it is meant to be. Science here has trumped both myth and religious devotion when it comes to preventing conception. And with the emergency morning-after pill more often at the ready, no unwanted pregnancy need ever occur.

Often confused with the abortion pill RU-486, which can be taken after pregnancy is confirmed, the morning-after pill is simply an “oops” pill — the cure for a broken condom or the one-night stands that Austrians are apparently known for. Its use is becoming more and more prevalent, and Austrians are lobbying loudly for it to be available over the counter.

But in the meantime, a solitary protester lumbers back and forth in front of the entrance to the museum, tepid in his approach toward visitors, edging toward indifference. He’s paid 5€ an hour by a pro-life group, and this is his full-time job. Occasionally he’s joined by others, usually American pro-lifers who have flown in from New York, since Austrians don’t seem to protest against a power they’ve worked so hard to gain.

Last summer a grad student, a sex educator, who was interning at the Museum of Contraception and Abortion needed help putting together a cabinet. She walked out onto the street and had a little chat with the professional protester. After a brief exchange, he set his plastic embryo down on the sidewalk, laid his rosary atop it, and followed her back inside to the museum, where she handed him a drill. • 2 January 2008