The idea for The Ugly Duckling, writes Paul Binding in his newly published Hans Christian Andersen: European Witness, came to Andersen on a walk. Andersen was already famous by then. He was staying as a guest at an estate on the island of Sjælland. Andersen always got himself invited to places like this — grand homes in faraway places belonging to people who would have otherwise ignored someone of Andersen’s class. Being an artist was like a special pass. With it, you could go anywhere and be anything.

Andersen hobnobbed with the upper classes but never felt quite at home with them. It was this unease, Binding suggests, that prompted The Ugly Duckling. Out on a walk, Andersen soon forgot his feelings of inferiority, and “felt instantly revitalized by all the summer beauty around him.” Andersen’s nature was a place of enchantment, free from the social hierarchies and injustices of the city. Of course, Andersen loved the city, too, because he loved culture. And, even though he often felt ridiculed and misunderstood, Andersen loved people — ordinary, forgotten people, in particular, people who weren’t artists or aristocrats, who often had no shoes. Maybe the countryside reminded him of the good and barefoot people. In nature, you could become simple. Thus Andersen began one of his most popular stories: “Der var saa deiligt ude paa Landet.” (“It was so beautiful out in the country.”)

Hans Christian Andersen never saw the countryside until later in his life. He was born in the crowded city of Odense, Denmark, in 1805. Odense was a very old city then, nearly a thousand years old. It was also marked, writes Binding, by alcoholism, “relentless poverty, unemployment, promiscuity, disease, crime both petty and serious, and mental degeneration often caused by too much hardship as well as by venereal disease.” These afflictions pretty well described everyone in young Andersen’s life, especially his family and neighbors. Andersen’s mother, a washerwoman who could not read, would die of “delirium tremens&rdquo in the same asylum where his grandmother spent her final years. Andersen feared his grandfather, who had also lived in the lunatic asylum, where he carved strange creatures, had a habit of wearing paper hats on his days out, and died “mentally deranged and with no money” at the age of 72. Andersen’s beloved father Hans, who introduced Hans Christian to Shakespeare and the fables of La Fontaine, was never quite right after coming home from war. In the last delirious stages of tuberculosis, Hans described to his 11-year-old son a maiden he saw in the iced-up winter windows.

Andersen’s countryside in Odense was the flowers his grandmother brought to the house every Sunday from the asylum. It was the garden his mother tended on the rooftop in a chest filled with dirt. These small incursions of beauty into the brutalities of daily life affected the young Andersen. In his stories, beauty often appears in this little way. It is a breeze, a glance, a candle, a seat at the theater, a rooftop garden, a pair of red shoes.

Hans Christian Andersen is commonly associated with The Ugly Duckling’s main character. Like Andersen, the Ugly Duckling is born into a family he doesn’t fit into. The Ugly Duckling is huge and gangly and odd. His mother decides to love him just the same, but the Ugly Duckling is not the same. The ridicule of others makes his difference apparent. “What sort of creature are you?” they ask him. “You are terribly ugly, but that’s nothing to us so long as you don’t marry into our family.” Like the Ugly Duckling, Andersen seems to have been born too large and too sensitive for his harsh environment. “I’ve never really experienced what youth was,” he wrote. “There is so much I want to forget, to learn something better.” As a boy, Andersen spent solitary afternoons with his marionette theater, preferred the company of girls, sang in an astonishing falsetto, had a soft place in his heart for Jews. After his father’s death, Andersen was sent to work, but he left Odense at the age of 14 for Copenhagen. Andersen found himself a patron to pay for his education, but was miserable at school. He never could shake the feeling that he lived in two worlds: the poverty he was born into and the bourgeois world of culture to which he aspired.

One day, the Ugly Duckling comes upon a group of swans. He feels happy just watching these magnificent birds. Could he dare to be like them? Perhaps they would peck him to death. Well, he thinks, better to be killed by swans than suffer. “Kill me!” he says to the swans, bowing his head over the water. It is then the Ugly Duckling beholds his image. He too is a swan!

Modernist sensibilities, Binding points out, find the ending of The Ugly Duckling unsatisfying, elitist even, as in the case of the critic Georg Brandes, who would have liked to see the Ugly Duckling murdered. At least, thought Brandes, the Ugly Duckling should make “one last, proud, solo flight” to affirm his ugliness. But, writes Binding, this is a failure to see Andersen’s art. It’s not that the Ugly Duckling discovers his superior magnificence when he looks at himself in the water. It’s that the Ugly Duckling sees his true reflection for the first time only at the moment he surrenders to death. This is the moment of the Ugly Duckling’s spiritual awakening. Brandes’ interpretation also assumes that Andersen’s ending promotes a fantasy, that an ugly duck really can become – or is – a beautiful swan. But for all his imagination – for all the talking candles and magical mountains and girls no larger than thumbs – Andersen was not a fantasist. He had seen reality in the cramped and filthy alleys of Odense, in the faces of the deformed and the wretched, and also in the transcendent grace of a garden. Andersen didn’t want us to think that all the Ugly Ducklings of the world are inherently swans. Rather, it is by recognizing who he truly is that the Ugly Duckling finds happiness. The spiritual awakening of the Ugly Duckling brings him closer to reality, because he wasn’t ugly after all. He wasn’t even a duck.

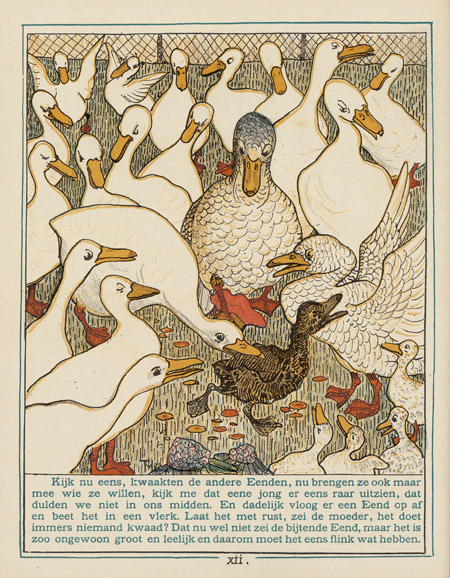

Page from a 1893 edition of The Ugly Duckling. Illustration by T. von Hoytema.

•

Innocence is often thought of as a quality projected outward. It means, literally, “not harm.” If a person is innocent, they aren’t going to harm you. But another way to consider the idea of harmlessness is that which is unharmed. It is a place within our own self, untouched by harm.

Hans Christian Andersen believed in an untouched innocence at the core of every person. “She cannot receive any power from me greater than she now has,” says the Finn woman of Gerda in The Snow Queen, “which consists in her own purity and innocence of heart.” Children had special access to this innocence – animals and grandmothers did as well – but the innocence was inside everyone. Innocence could be hidden and emerge, or it could be apparent and then corrupted. See, for example, the devil’s mirror in The Snow Queen, which had the peculiar power to make everything good and beautiful seem like nothing. The loveliest landscapes looked like boiled spinach and the very best people became hideous or stood on their heads and had no stomachs.

To be wholly innocent was rare. To be wholly innocent, for Andersen, meant to be wholly yourself. It meant that you were free from the distorted reality of the devil’s mirror. There is a connection in Andersen’s work between innocence and reality, then, because innocence is truth. And just as truth is eternal, so is innocence. Though many of Andersen’s tales are tragedies, ending in death or humiliation, they all affirm the importance of a life lived toward an eternal, personal truth. This is what Andersen meant when he said, “Every man’s life is a fairytale, written by God’s fingers.” This doesn’t mean that every man’s life is a fantasy. It means that every man’s life is a quest toward reality.

In Andersen’s fairytales, finding one’s truth is rarely easy, and there is no single way to get there. As Binding writes, the strength of Andersen’s art lies in “his refusal to ignore pain and frustration even while presenting the beauties of sentient lives and their capacity for mutual tenderness.” Reality can be discovered through self-sacrifice, as with Gerda in The Snow Queen, when she casts her red shoes – her only prized possession – into the water so that she may find (and save) her lost friend. Reality can also be found through repentance, like with Anne Lisbeth, who tries to give her soul to the dead son she neglected. The child in The Emperor’s New Clothes discovers truth through fearlessness, and his fearlessness brings the Emperor closer to truth as well. The Ugly Duckling doesn’t have to do anything special to become his true self. He just has to surrender and be.

The Little Mermaid is the tale of a young mermaid who wants nothing more than to be a human. Human beings have short lives, she learns, but they have souls, and so share in the eternal. Mermaids have no souls. They can live for three hundred years in the glorious underwater kingdom of the sea, but when they die, they become nothing but foam. The little mermaid falls in love with a prince she sees on shore; to get a soul, she must make the prince love her back. So she gives up mermaid life forever – risking everything she has – and becomes a mute, soulless human. Alas, the prince marries a princess. The little mermaid must become foam. In one last shot, the little mermaid is given a chance to become a mermaid again, only she must kill her beloved prince. She chooses annihilation. Yet, just when all hope looks lost, the little mermaid is taken up by the Daughters of the Air, who win souls through good deeds.

No tale of Andersen’s shows the pain of finding one’s soul so much as the heartbreaking The Little Match Girl. “It was so terribly cold,” the story begins. “In the cold and the gloom a poor little girl, bareheaded and barefoot, was walking through the streets… In an old apron she carried several packages of matches, and she held a box of them in her hand. No one had bought any from her all day long, and no one had given her a cent.”

The little match girl shivers through the streets, and notices the lights in the windows. The air smells like roast goose. It is New Year’s Eve; the little match girl hadn’t realized until then. She is cold but doesn’t dare go home. The little match girl’s father will beat her when he learns that she hasn’t made a cent. She finds a corner between two houses, sits down, and lights a match. It makes a warm bright flame, and when she strikes another match, it turns the wall into a window. The little match girl sees into a wonderful room, decorated for Christmas. When she lights another the room is even more wonderful. In the glow of the next match, she sees her kind grandmother. “Oh, take me with you!” she cries, and lights the whole bundle of matches to keep her grandmother close. In the morning, the New Year’s sun rises on the pathetic corpse of the little match girl. “No one imagined what beautiful things she had seen, and how happily she had gone with her grandmother into the bright New Year.”

•

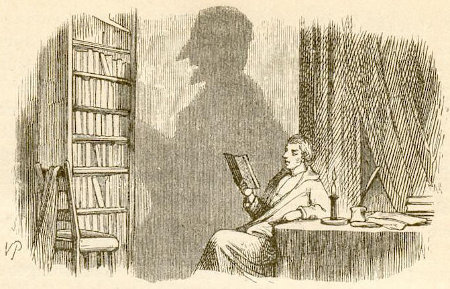

Illustration by Wilhelm Pedersen from an 1849 edition of The Shadow

There is the feeling, when reading Andersen’s work as a whole, of something unresolved. What to make of all these inconsistent endings? Is it best to be an artist – to attain innocence via works? Is it best to help others find their reality? Does one find reality through anonymous acts of love, or by being good, or just by being? Andersen never resolved the contradictions within himself; his stories are reflections of an unresolved man. Had their endings been any tidier, any more consistent, they wouldn’t have the same power. Andersen’s characters never know where their spiritual journey will take them, or how it will all pan out. Only one thing is sure: they all have to go. They have to face life’s truth by facing eternity, and not get lost in illusion.

The greatest danger in all of Andersen’s fairytales, therefore, is the constant danger of self-delusion. You can easily deceive yourself into believing you’ve found your truth when, in fact, you haven’t. The Shadow’s protagonist is a scholar who has traveled to a hot and faraway country. In countries like this, travelers’ shadows can get very big and take on lives of their own. This is what happens to the scholar. One evening his shadow just takes off, leaving the scholar quite annoyed. The scholar gets on with a perfectly good new shadow and goes home to write books about the things in the world “that are true, that are good, and that are beautiful.” Then one day, the shadow returns, looking distinguished. “How goes it?” he asks the scholar, and the scholar replies, “Alack! I still write about the true, the good, and beautiful, but nobody cares to read about such things. I feel quite despondent…” The shadow tricks the scholar into becoming his friend. He convinces society people that he is the master and that the scholar is the shadow. The shadow has gotten on well by himself, and wants to become a man. To do so, the shadow must get rid of the scholar. This is, indeed, what happens.

Carl Jung was fascinated by The Shadow. His interpretation could be summed up: Know your darkness or else. For it is only in knowing your darkness that you can hope to conquer self-delusion. The complacent scholar couldn’t even recognize his own shadow, and in the end his shadow overcame him. Still, Jung was sympathetic to the scholar. To become conscious of one’s shadow, he wrote, takes “considerable moral effort.” It involves “recognizing the dark aspects of the personality as present and real.” As he wrote in On the Psychology of the Unconscious (1912):

It is a frightening thought that man also has a shadow side to him, consisting not just of little weaknesses and foibles, but of a positively demonic dynamism… let these harmless creatures form a mass, and there emerges a raging monster; and each individual is only one tiny cell in the monster’s body, so that for better or worse he must accompany it on its bloody rampages and even assist it to the utmost. Having a dark suspicion of these grim possibilities, man turns a blind eye to the shadow-side of human nature. … Yes, he even hesitates to admit the conflict of which he is so painfully aware.

We all think of ourselves as good. Andersen would agree; goodness is part of our reality. But shadows are reality too, and if we never face them, we can never get to truth. How different the scholar’s relationship to shadows than the Little Match Girl’s. The match girl is her shadows and the shadows are her. She goes so deeply and fully into the shadow world that she transcends it altogether. The scholar, in contrast, is overtaken by his shadow, is imprisoned by it and killed. The shadow lives on alone, pretending to be a man, growing stronger and richer, free from the burden of the scholar. He marries a princess and no one knows what he really is. “The cannons boomed, and the soldiers presented arms. That was the sort of wedding it was! The Princess and the shadow stepped out on the balcony to show themselves and be cheered, again and again. The scholar heard nothing of all this, for they had already done away with him.” • 30 June 2014