It’s an ambiguous pileasure, but a pleasure nonetheless, to look back at the photographs I took decades ago when I was in my teens and early 20s. Those images make me realize there are moments that seemed so consequential to me, that felt so charged with happiness and meaning, that I felt compelled to make a record of them. They also remind me that I was once young and dewy and that I am not so any longer.

These photographs have a random, desultory quality to them. Each one is like the proverbial insect that got stuck in amber. If things had been different on some particular day 150 million years ago, if a different unsuspecting fly or beetle had blundered its way to its sticky doom, then the chunk of cretaceous petrified tree resin that I hold in my hand would display a different mummified arthropod. It’s the same with all these photos I have of people I didn’t know, or barely knew — friends, or friends of friends, or other young people who frequented the same bars and restaurants long ago.

Most of the photos were taken with a 35mm Olympus camera my father gave me as a birthday present in 1981. When I was 13, I didn’t think to ask for or even to want a fancy camera. I was more interested in getting my own stereo so that I could listen to Blondie 45s in my room. It seemed to me that my father did a perfectly good job of taking family photos with his Nikon camera and I even had an Instamatic that I could resort to in extremis. Still, he wanted me to have a really good camera; he had always loved taking pictures and thought that I might too one day.

I brought the Olympus with me to stave off boredom during the obligatory attendance at my brother’s soccer games, which is the reason why I now have charming photos of the boys I went to high school with wearing their sweaty, grass-stained uniforms. In college, I got in the habit of lugging the camera around on weekends when I left my suburban campus for Boston: on exciting, unpredictable nights when I didn’t quite know where I might go and what might happen. The camera, an encumbrance on the dance floor, provided an excuse to sit out the dancing since the evening’s photographer had the unspoken right to drink rum and cokes on the sidelines while waiting for a picturesque excuse to snap the shutter.

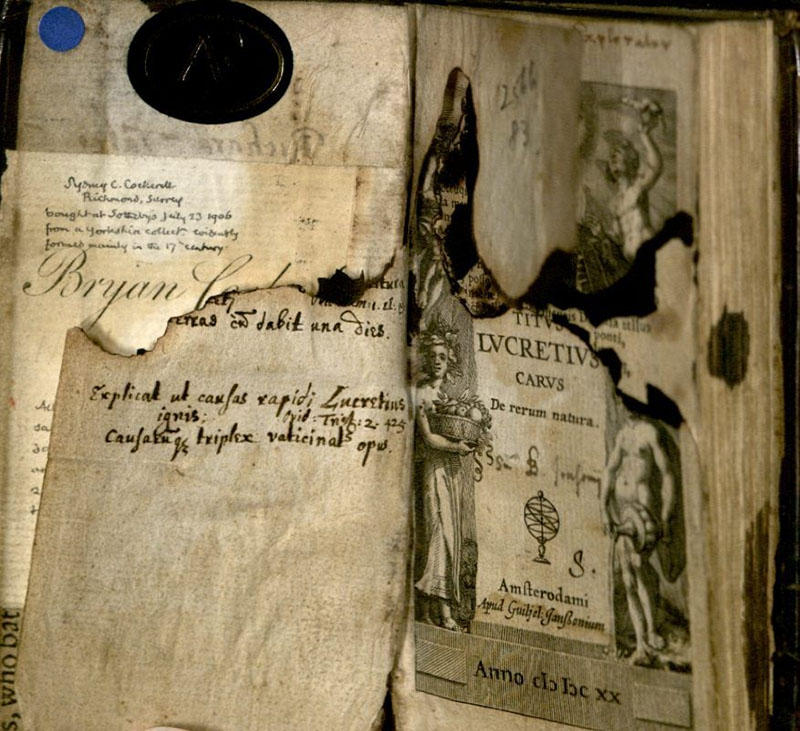

I think the key thing was the literal and figurative weightiness of the camera. I took it out for special events or when I wanted to make ordinary events special. It recorded things, but its presence changed the atmosphere and the images being taken. Thirty years ago, cameras weren’t ubiquitous. Even if the subjects were encountered at random, making photographic images required some commitment. It strikes me that my photos taken back in the 1980’s and 1990’s have a good deal in common with carefully posed daguerreotypes — perhaps more than they do with the throwaway digital images I have on my smartphone today.

For most of history, of course, there were no cameras, no way for ordinary people to record the visual with any measure of verisimilitude. Even after the 1839 introduction of the first camera for professional photographers, the Giroux Daguerreotype, it took another 50 years for George Eastman to bring to market the easy-to-operate, amateur-friendly Kodak. Then, right at the turn of the century, he came out with the small, portable, one-dollar Brownie camera — which made the technology available to just about everyone. Portability is relative, however. I took my childhood Instamatic with me on the junior high field trip from Albany, New York to the Boston area, where I struck a sassy pose in front of Concord’s “rude bridge that arched the flood,” along with pre-teen girls named Andrea, Pam, and Lara. That camera and the low-quality snapshots it tended to produce now seem as archaic as Emerson’s anachronistic poetic diction.

Today I am a librarian at a university and have plenty of opportunities to observe college students. They are, as we all are now, a little trigger-happy when it comes to the cameras on their smartphones. Still, they’ve been taught to be nervous about exposure — and I’m not referring to the amount of light hitting a camera’s sensors. Incriminating photos, posted thoughtlessly or even maliciously, can ruin a reputation or repel a potential employer. They can even go viral. I try to imagine how stultifying it must be to have to worry about the omnipresence of camera phones and Facebook, the fear of being captured chugging beer at a keg party or puffing on a joint in a friend’s dorm room. I’ve added this low-grade but constant anxiety to the list of reasons why I don’t envy today’s college students, along with the high cost of tuition and the dismal job market for recent graduates.

If you’re worried about the potentially compromising future uses of your photographs, it’s easy to forget to question whether those images will actually have a persistent afterlife. My sense is that the longevity of today’s photographic record is in question; digital images are less stable than those printed on high-quality photographic paper. Decades from now, today’s college students might not have a photographic record of their undergraduate years at all.

There was data loss before the internet of course. To use literature as an example, Sappho, whose work is now only available in tantalizingly fragmentary form, is one well-known example. Her poems were recorded on papyrus, a writing material from Egypt that was used in the ancient world as an alternative to more expensive (and, as it happens, more durable) parchment. Archivists and fans of Thomas Pynchon will recognize the characteristic disintegration of papyrus over the centuries as an example of “inherent vice” (that is, the way in which a material’s own chemical makeup leads to its self-destruction).

There’s also data loss due purely to human neglect. In the 17th century, Ben Johnson bemoaned the loss of a painting in his poem “Picture Left in Scotland.” In it, he regrets having entrusted a portrait of himself to a woman who didn’t love him enough to take good care of or appreciate his gift. He expresses regret too that he is no longer young. He seems to have hated the sight of his middle-aged self in the portrait, and hated even more the fact that the woman he was enamored with clearly didn’t care for it either. “My hundred of gray hairs,/Told seven and forty years,” he wrote, adding ruefully: “she cannot embrace/ My mountain belly and my rocky face.”

I feel his pain, having just turned 47 myself.

The carelessness with which the painting was forgotten wounded him, but it wasn’t tragic; the reader senses that aging Ben was probably better off without the heartless little minx. The loss of the current college generation’s photos — images of poignantly young people who will inevitably grow apart from one another — won’t be a tragedy, either, perhaps; as I say, ordinary people have only had access to photography for a bit more than a century, and it’s possible today’s college students will not miss what their distant ancestors never had: a photographic record of the past. Still, I think it’s hard for one generation to accept less than what the previous one had, and I think it is painful to lose what could have been saved. What’s more, I believe there will be a collective data loss that affects millions of people and alters future generations’ ability to know us through our creations and artifacts.

Digital preservation requires conscious effort. Unlike in the analog world, digital photo albums shouldn’t be abandoned for decades if one wants their contents to remain accessible. Without constant vigilance (old files, for example, being migrated to new formats) those photos won’t be available for viewing years from now. Archival studies scholar and photographer Jessica Bushey has noted that the cloud-based services consumers use to store photos take no responsibility for preserving them; the Instagram Terms of Use contract, for example, states, “We reserve the right to modify or terminate the Service or your access to the Service for any reason, without notice, at any time, and without liability to you,” and also, “Instagram encourages you to maintain your own backup of your Content. In other words, Instagram is not a backup service and you agree that you will not rely on the Service for the purposes of Content backup or storage.” In other other words, Instagram, like most social networking sites, refuses to promise to back up data, while retaining the right to cut off access to the site without notice. Instagram isn’t Snapchat (which, due to the supposed ephemerality of its images, has distinguished itself as the go-to photo sharing service for dick pictures). Instagram, like Facebook, is a service users turn to for images that they actually want to save.

Instagram, then, takes us back to Ben Jonson’s early modern era — and not just because of the seemingly whimsical capitalization employed in the Terms of Use. In the decades ahead, we will have to start taking more care to preserve images, not because they are rare (as they were in Jonson’s day) but because they are more fragile than we may think. Doing what I did a quarter century ago — that is, stash my photographic prints in an album and then forget about them for long periods of time — simply won’t be feasible. Either we’ll take good care of our images and not entrust them to unreliable stewards or we will, like Ben Jonson, suffer loss and perhaps even long-term regret.

Many commentators have noted the Faustian bargain we’ve made with the likes of Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram: in exchange for a purportedly free service, we have handed over our personal data to corporations. Furthermore, the so-called “culture of free” has eroded the ability of musicians, photographers, and writers (among others) to make a living from their work. Less examined is the inability of free services to preserve our data. The aforementioned internet-based services make money selling data, not preserving it, and obviously corporations exist to make money. This means that they will preserve our images stored on their servers only for as long as it is cost-effective to do so — and not a moment longer. There have been hacks of websites — Target’s for example — that have led to data leaks. But as we wring our hands over the potential for identity theft, we should remember that any hacker who can steal information could, of course, also erase it. (This happened to Wired writer Mat Honan.) Furthermore, time is the ultimate thief of digital information. The slow-motion erosion of papyrus over the centuries is nothing compared to the rapidity of data loss in a digital environment. Files crash, and new iterations of hardware and software can make old data inaccessible.

My own smartphone is filled to capacity with images that I’ve failed to back up, even though I know well how easy it is to lose them. Internet culture has come to favor dissemination over preservation, and it has encouraged users, even vigilant ones like me, do the same. It’s easy for me to post images that can be viewed by millions, while properly saving my images takes effort and even some money. In spite of my hundreds of gray hairs and my 47 years, I, short of time and cash, fecklessly procrastinate rather than immediately create satisfactory backups of everything I own and want to save. Every time I look at my old college photographs I feel grateful to have grown up in a time when careless handling of images didn’t lead to catastrophe — viral images whose spread is impossible to halt or lost photographic treasures that even an expert may not be able to retrieve from oblivion. •

Images courtesy of Osmow, Susan, John Overholt, and Kadorin via Flickr (Creative Commons)