If you are lucky, and if you happen to be on the Dutch shore of the North Sea, and if it is a windy day (a not-unusual occurrence), you just might see a new sort of creature walking down the beach. This creature will be walking in fits and starts, activated by gusts of wind, animated in one part of its “body” and then another. Atop the creature, you will see sheets of fabric that look like sails of a small ship. Upon closer inspection, you’ll notice that the rest of the creature is made entirely of plastic tubing, what’s known as PVC. PVC stands for “polyvinyl chloride.” The white plastic tubing you’ve seen in thousands of bathrooms and kitchens is PVC. Upon even closer inspection, you’ll notice that the creature is made of PVC and nothing else. You’ll ponder that for a moment. Nothing but PVC. How does it move, then? Isn’t there a motor somewhere? Aren’t there electronics on the inside telling the creature when and how to move? You’ll become shocked and disoriented by the realization that the creature isn’t controlled from anywhere else or by anyone else. It is simply walking of its own accord, having a little stroll on a windy day along the beaches of the North Sea, as if it were alive.

While the beach creature is self-propelled, it is not self-made. The creature has a creator and we know that creator’s name: Theo Jansen. Jansen is a Dutch man who has played many roles in his life: physicist, landscape painter, engineer, art prankster (he once built a mini-UFO that he flew around the city of Delft, scaring the shit out of people). At the end of the 1980s, Jansen became obsessed with the idea that the rising water levels of the world’s oceans would doom the Netherlands (which means “lowlands”) to a soggy future. This is a longstanding worry for people of Dutch extraction. You’ve heard, no doubt, the story about the little Dutch boy who stuck his finger in the dike. As every Dutch person knows, Holland as we find it today would be under water if not for the complicated series of dikes, water channels, earthworks and the like that keep the country from being reclaimed by the North Sea.

Theo Jansen decided that his contribution to keeping the Dutch dry would come in the form of an army of robots. He would build self-propelled creatures that could be let loose on the beaches of Holland in order to move sand around. These robots would be the mechanized version, as it were, of the little Dutch boy with his finger in the dike. The mechanized creatures would pile up sand day and night, tirelessly protecting the shoreline of the nation from the rising seas.

A.SCHLICHTER4 from Strandbeest on Vimeo.

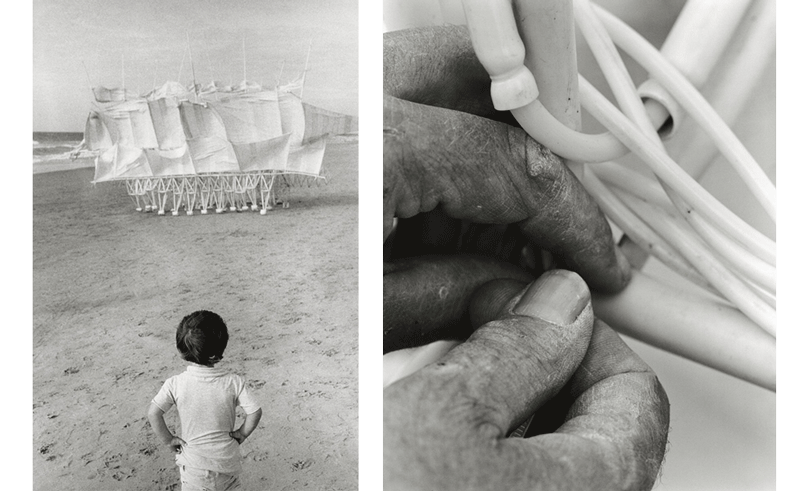

Jansen had only one problem. How to build such mechanized sand movers? He wanted the machines to be simple and cheap in their design—thus the use of PVC. He studied the mechanics of all kinds of legs: legs on people and on four-legged mammals and insects and manmade machines. He wanted to find the simplest and most efficient means by which you could get something moving of its own accord.

In the process of trying to solve this relatively clear-cut engineering problem, Theo Jansen found himself stumbling headlong from the realm of mechanics into the realm of metaphysics. That’s because he wanted to find a way to make an assemblage of plastic tubes move without cheating. “Cheating” would be to add some sort of external motor or driver. Jansen’s desire not to cheat was born of practical considerations. The idea, remember, was to unleash a whole army of these walking machines. Each “soldier” in this sand-moving army would have to be cheap, simple, and self-contained.

As Jansen experimented with different ways to make plastic feet and joints and “legs” and “knees,” he was pulled further away from the external goal (an army of sand movers) and further into an internal goal (how to make the plastic “come alive”). Over the years, Jansen started to get bits of plastic to cooperate with one another and move around simply with the impetus of a gust of wind. The resulting many-legged, self-propelled, beach-cruising “beasts” move with such amazing – albeit jerky – fluidity that it is easy to label them organic. Seeing this, Jansen began to ask himself strange and deep questions like, “Are these things alive?” and “Have I created a new species?”

Compilation from Strandbeest on Vimeo.

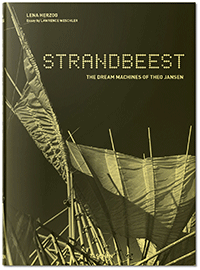

You can find tons of videos on the web showing various versions (or “generations”) of Jansen’s creatures from the last 20 years. The video on the main page of Theo Jansen’s own website is my favorite. That’s because it opens with the shot of a woman standing on the beach between two of Jansen’s creatures. She has her back to the second creature as she takes a picture or shoots some video of the first. Suddenly, the wind increases. The creature behind the woman lurches forward. What’s going to happen? It is like watching a nature video showing wild beasts interacting on the plains of the Serengeti. At the last moment, the woman turns around and sees the beast lumbering toward her. She moves out of the way with the same sort of respectful steps you would use to move around a large animal — like a horse or elephant. She realizes that the beach creature is not being operated by remote control. It has its own will, which must be respected. That woman’s mincing steps are a more eloquent proof of “aliveness” than any verbal theory.

Read It

Strandbeest: The Dream Machines of Theo Jansen by Lena Herzog, Theo Jansen, and Lawrence Weschler. Available now from Taschen.

If you need further proof that the beach creatures are alive, take a look at the photographs taken by a longtime admirer of Theo Jansen, Lena Herzog. Herzog’s photographs can be seen in a new Taschen publication Strandbeest: The Dream Machines of Theo Jansen.

On the face of it, taking still photographs of Jansen’s beach creatures is a strange thing to do. We are delighted and amazed when we see the beasts lumbering across the sand. Seeing the beasts frozen in photographic stasis, however, is akin to looking at piles of inert plastic lying on the beach. What’s the point?

But couldn’t the same thing be said of pictures of human beings? What’s the point of looking at a picture of a bag of flesh and mostly water sitting in its home or standing in front of a monument in some distant land? The only interesting thing about human beings is that we move around and do stuff. A picture of a human frozen in time is a kind of lie, isn’t it?

Nevertheless, we do like to look at photographs of human beings. We care about human beings; they mean something to us. Photography gives us the chance to hold onto images of ourselves and our fellow creatures, to gaze at those images in contemplation, to fix in semi-eternity what is otherwise fleeting.

And that is exactly what Lena Herzog has done, quite movingly, with the beach beasts of Theo Jansen. She’s photographed them as you would photograph a beloved friend or a dog that you’ve lived with for many years. Herzog’s photographs are not so much acts of documentation as acts of tenderness. I’ll give an example of what I mean.

On page 86 of the book there is a black-and-white photograph of one of Jansen’s creatures on the beach. We only see the left far section of the beast. It is at rest, although the wind seems to flap a bit at its top “sail.” Standing in the foreground of the picture are two young girls. The girl on the left raises her face to the sun and her right hand rests on a plastic crossbar of the beast. The second girl looks over her shoulder, directly into the camera. She too is grasping the plastic bar of the beast. The girls are holding the beast gently. They care about it. They like it. Maybe they even love the beach creature. The young girls seem involved with the life of the beast in the same way that they might be involved in the “life” of any other living creature. They will be happy if the creature manages to get itself going and move along the sand. The girls will be very sad if the creature – as happens often enough with Jansen’s beasts – founders and collapses of some inner malfunction.

There’s another picture on pages 212-213. The foreground of the picture is all beach. There’s a slight sheen of water on the sand, giving a dim and blurry reflection of a creature. At the top of the picture, we see ten or fifteen plastic “legs” and “feet.” The “feet” are made from what seem to be strips of white rubber wrapped around the end sections of PVC. Looking at those feet, I’m reminded of Jo Farrell’s recent photographs of the last generation of Chinese women to have bound feet. The beach creature’s feet have something of that same vulnerable quality.

But more than Farrell’s photographs, Herzog’s shot recalls one of Walker Evans’ famous pictures of Depression-era sharecropper families. There’s one shot in particular, taken sometime in March 1936. The photo is known as “Sharecropper’s Family, Hale County, Alabama.” It shows an older woman, a youngish couple, and three children varying in age from an infant to a boy who is probably nine or 10. Walker took this photo as part of his now-legendary work for the WPA, documenting social conditions in rural America. The photograph is, on its surface, a socioeconomic statement. It is about the living conditions of rural sharecroppers.

But the photo is also about feet, naked feet sprawled and tucked all over the bottom half of the picture. The nakedness of the feet becomes a metaphor for the overall nakedness of the situation, the stripped-down and utterly exposed nature of this rural poverty.

But then again (and this is why the picture is great), the feet don’t project defeat (excuse the pun) and do not ask for pity. The father’s feet are planted firmly on the floorboards of the shack and match his stoic – though in the end kindly – gaze. The feet of the oldest child have the crinkled-up toes that bespeak the onrushing self-consciousness of early adolescence. The mother rests her feet on their edges, one in front of the other, with the same combination of modesty and ease expressed in her face and posture. Then there is the older woman, presumably the grandmother. She wears (and the mind reels that this is possible) Van Gogh’s peasant shoes. How in the world, we wonder, did she get them?

Staring at the photograph for any length of time, a thought comes to mind. Naked feet reveal much. It takes great strength and confidence, even nobility, to sit in front of a camera and reveal so much. By showing us their naked feet, the members of the sharecropping family from Alabama have transcended the largely representative role they are supposed to play in the picture. They’ve become fully realized human beings.

I digress simply to point out that something similar is happening with Herzog’s photograph of the feet of the beach creature. The feet of the plastic contraption do not look mindless and mechanical. They look hardworking and vulnerable. The foot on the far left of the picture even looks like it might be wounded. Look how the creature holds that foot slightly off of the ground, like it doesn’t want to put weight on it. I want to use the word “wounded” specifically. You don’t talk, for instance, of an automobile being “wounded.” You say that it is broken and needs to be fixed. The beach creature’s foot is not broken; it is wounded and needs care.

It is through these vulnerable “body” parts of the creatures that we come to understand the full creatureliness of Jansen’s creations. Through their “feet” and “legs” and “arms” and “hair” we shall know them. Flipping through Herzog’s photographs it is possible to say, “If these creatures are not alive, then nothing else is either.” Lena Herzog has created, in essence, the family album for a new form of life. •

Photos courtesy of Taschen and © 2014 Lena Herzog.