Shakespeare, we know, was a deft hand with the words but not much of a plot guy. So besides lifting scenarios from Plutarch, Holinshed, and the classics, it made total sense for him to work with collaborators in devising plays with public-pleasing story arcs, shaped by the revisions and additions of multiple authors like Fletcher, Middleton, and Kyd.

None of them were any great shakes as dramatists, but their product could be relied on to generate boffo profits. And who wants to say no to boffo profits? That question frames the dilemma of two 20th-century writers who functioned as an extremely successful team. As was famously the case with Gilbert and Sullivan, one collaborator came to loathe what he was doing and ultimately channeled that hostility towards the other partner, who responded in kind.

Read It

Blood Relations edited by Joseph Goodrich

You’d have to sit through the second act of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolfe twice to find anything comparable to the acrimony and shredded feelings on display in Blood Relations, a gathering of what editor Joseph Goodrich claims is all that survives of the life-long correspondence between Daniel Nathan and Manford Emmanuel Lepofsky, two first cousins out of pre-World War I Jewish Brownsville.

The infant “Dan” got an early break when his parents moved to the bucolic upstate town of Elmira, New York, formerly home to Mark Twain, while bookish, vulnerable “Man” was left to fend for himself on the mean streets of “New York’s rawest, remotest, cheapest ghetto,” and be reminded of the rural raptures he was missing out on when their families reunited over the summer.

Years afterwards, that festering sense of unfairness would become a recurrent point of inflection in the letters written by the left-behind cousin, who by then had changed his name to Manfred Bennington Lee. It couldn’t have helped when, in later years, the other cousin, who had meanwhile changed his name to Frederic Dannay, brought out his only work of fiction not written in collaboration. The Golden Summer is a syrupy, cliché-choked account of pre-adolescent boys who have “avenchers” in a small upstate town where fresh baked pies cool on every windowsill. Their blissful summer is interrupted by a visit from the 12-year old hero’s uptight, scaredy-cat, overweight, city-slicker cousin, Telford (cf. Manford), who is ridiculed in a way too edged to be dismissed as friendly leg-pulling.

“We were closer than brothers,” Dannay would later insist. Both were working as entry-level PR hacks in 1927 when a contest was announced offering a book contract, magazine serialization, and $7,500 cash up front for the year’s best mystery novel by a new writer. The pair entered and won, but the magazine went bust. The publisher, however, offered them a $200 advance, so they decided to go ahead with a writing career anyway.

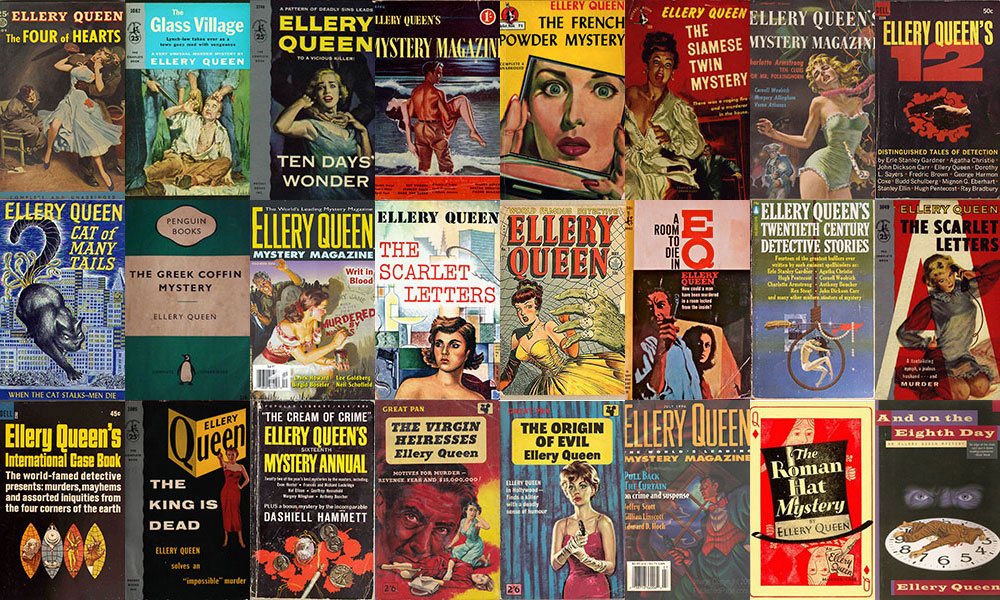

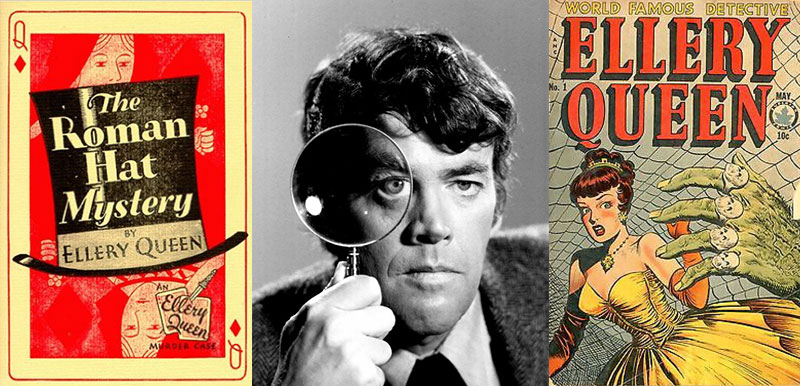

The author’s name on the title page of The Roman Hat Mystery is that of the book’s central character. The fictional Ellery Queen is a writer of best-selling detective stories gifted with stupendous powers of deductive reasoning, ratiocination, and self-conceit, who accompanies his father, a crusty NYPD homicide inspector, as they investigate a multiplicity of murders that have the cops baffled and the city’s newsboys shouting their lungs out. Some 300 pages later, Ellery reveals his equally far-fetched solution to the crime.

While Agatha Christie and Rex Stout were concocting durable series characters from spec sheets of endearing quirks, the cousins cloned their hero off a second-banana sleuth named Philo Vance who featured in some of the most atrociously bad genre fiction ever to defile jazz age best-seller lists. Early Ellery solves elaborate puzzles constructed out of conspicuously red herrings, suspects acting suspiciously, mutilated corpses, false identities, missing millionaires, hysterical heiresses, locked rooms, and housemaids who scream on cue to signal that a body has been found. Deciphering a “dying message” considerately scribbled by the murder victim when in extremis became Ellery’s trademark deductive shtick and remained so until the final novel in the canon was published in 1971.

As one would imagine, the clues that identify the guilty party would never be admitted as evidence in any court of law where flamingos are not being used a croquet mallets. Hence, the scene in which all the suspects are rounded up to hear one of their number get nailed often leads the murder to either confess on the spot or make a self-incriminating run for it.

In The Roman Hat Mystery and the equally formulaic adventures that followed, Ellery shares digs with his dad in a brownstone on West 87th Street, where they are attended by a “houseboy” (don’t ask). Harvard-educated Ellery is chaste, learned, and beyond insufferable. He wears pince-nez eyeglasses and drives a Duisenberg. “The biggest prig who ever came down the pike,” is how his co-creator Manny Lee described him.

At the start of their collaborative career, the cousins were much in demand for book signings, where they appeared with faces masked and identities concealed. On one occasion, Dashiell Hammett, who was in the audience, unobserved and in on the secret, zinged them with: “Mr. Queen, what can you tell us about your famous character’s sex life, if any?”

In lieu of a strongly defined central character, the cousins had a standing gimmick. With only few pages left to turn, Ellery announces, “Dad, I think I know who did it,” and proceeds to inform the reader that all clues have been revealed in plain sight and invites him to identify the guilty party before the detetive can.

The “challenge to the reader” was dropped as the character matured over the following 43 years, while the scenarios dreamed up by Dannay modulated towards the somewhat less bizarre. But the solution to an off-the-wall puzzle remained the unforgiving armature over which everything had to be layered.

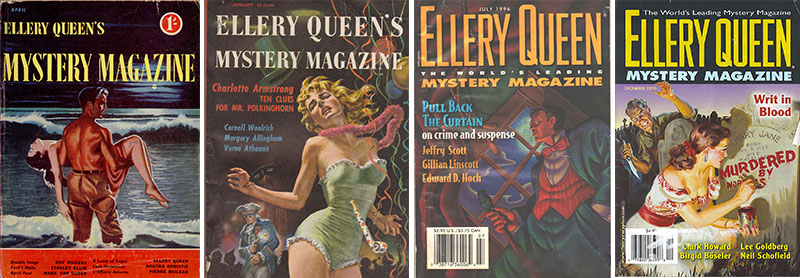

It was not until the 1940’s, though, that the Ellery Queen brand really took off, thanks to a radio program supervised and scripted by Dannay and Lee in which their hero was finally allowed a none too convincing romantic interest and comic relief, while members of the audience and celebrity guest stars took turns deducing the murderer’s identity. The show attracted 15 million listeners at its wartime peak, and library shelves sagged under what finally totaled out at some 40 novels, anthologies, and story collections.

It’s hard nowadays to sense the appeal of a fictional artifice in which every development has only to be consistent with the plot’s internal logic and with nothing else in this world. Plausible or not, Ellery’s methods bring to mind a Jewish archetype: that of the righteous, intellectually gifted man (Talmudic scholar) who uses hermeneutic methods (intuition, reflection, deduction) to determine the significance of attributes (clues) that, when correctly interpreted, reveal that which is hidden (the murderer’s identity).

The detective as Kabbala-certified cryptographer is a conceit brilliantly mined by self-declared Ellery Queen fan Jorge Luis Borges in his story “Death and the Compass.” Another Borges classic, “The Garden of Forking Paths,” was the Argentinian writer’s first story to be translated into English, appearing in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in 1948.

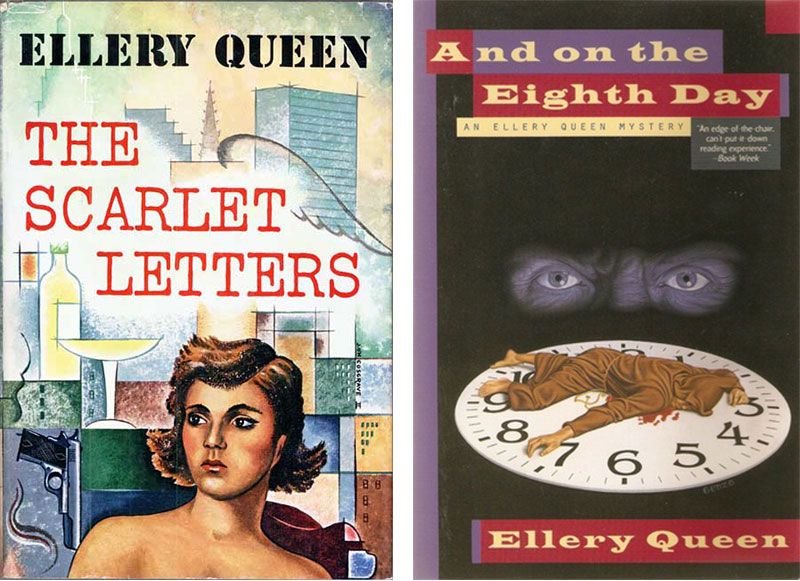

Novels by the Queen team convey their personal opinions on matters such as McCarthy era politics (The Glass Village) or midcentury American sexual mores (The Scarlet Letters). Like G.K. Chesterton, they found that the detective story readily lendt itself to religious conjecture. “The Lamp of God” is an early tale that has Ellery speculating on divine revelation as the source of illumination that allows human intellect to perceive the truth. A character in Ten Days’ Wonder is clearly a stand-in for the Old Testament Jehovah: arbitrary, despotic, and given to extreme mood swings.

And on the Eighth Day was one of the later titles in the saga, and as such, received no input from Manfred Lee, who was sidelined with writer’s block at the time of its writing. Inspired by Edmund Wilson’s 1945 New Yorker pieces on the Essenes, the sect that produced the Dead Sea Scrolls, Dannay has Ellery stumble across a crime and sin-free Eden in the desert where he examines messianic belief systems from the inside and reflects on the distance separating faith and reason when a murderer goes free.

Quite often, the cousins would be queried as to who wrote what. During the fecund years of their partnership, the question was routinely ducked, and after Lee’s death in 1971, Dannay declined to comment. It is known now that Fred saw to the plotting, sketched out the characters, and devised the puzzle and its solution. He all but admitted he couldn’t write fiction for beans. To make up for that, nature made him a gifted editor who midwifed the careers of dozens of writers in the crime and suspense field through his hands-on editorship of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and helped develop an American readership for foreign writers like Georges Simenon.

Manfred Lee was the writing workhorse. He would take a 20,000 word, 70-page outline devised by Dannay and flesh it out with all that a writer is supposed to have at his command, including a sense of narrative pacing, a distinctive literary style, the ability to depict character with all its consistencies and contradictions, and the judicious management of detail, description, and dialogue. In short, he had all the right equipment except the ability to devise a compelling narrative.

Thanks to the radio show, the fictional Ellery became a seriously money-making property around the time Manfred Lee’s disdain for what he was doing approached the intolerable. With six children and two stepchildren to support, dissolving the partnership would have been folly. Manny told one of his daughters he considered himself a “literary prostitute” and kvetched in a 1947 letter to critic Anthony Boucher that he:

… chafed for years under the glossy, artificial brittle manufactures put out under the Queen name — little edifices of taffy offered to a world hungry for substantial fare — all under the name of “escape literature.” Fred’s enthusiasms for the detective short story historically, the little puffings of chest, etc. and the making out of detective stories what they never were and can never be, have always left me dissatisfied and a little ashamed. I admit he has done a wonderful job of selling, and in the selling has quite managed to obfuscate the truth — which is that the majority of the vast literature of detection, short and long, is hogwash, illiterate and mechanistically mystic in a world crying for art to grapple with reality.

Before long, what had begun as a dispute between two skilled craftsmen ,arising out of their deep differences in literary aims and standards, turned poisonously personal. But certainly Manny Lee had his work cut out for him trying to leverage some degree of credibility into Fred’s extravagant scenarios.

Man to Dan, Jan. 23 1950

Within the demands of necessity, you have carefully, sometimes brilliantly worked out what must follow. While recognizing, even applauding all this, I still look at the result and I must say, “But how fantastic. Who would — could — do such a thing?” Nobody human. It doesn’t ring true to life in exactly in the proportion it was brilliantly conceived. The more brilliant, the less true, the less convincing. Yet I have to write this story in terms of people in a recognizable ‘realistic’ background.

Dan to Man, July 2 1948

Well, Man, if it is true you do not like the new novel, the hell with it. It’s okay with me. In fact, if you should happen to dislike it intensely, then send back the whole fucking outline to me and that’s that. All that will be lost is my time, my work and health.

The letters reveal a Manfred Lee who is hair-triggered to take offense and a Fred Dannay that is always on the defensive but, even when choosing his words carefully, cannot help making things worse with what Lee interprets as attempts to patronize him.

Man to Dan, May 9 1949

You have an utter loathing and contempt for me and my work… I’m the inferior: you’re the boss. Papa knows best. You have never once in twenty years been able to resist rubbing my nose in the dirt, when events have proved me wrong, as they frequently have … We’re both bad losers but you’re also a bad winner. And that’s one charge I don’t think even you can hurl at me.

What kind of curse is on you and on me that makes these ridiculous, wasted, bitter venomous exchanges unavoidable?

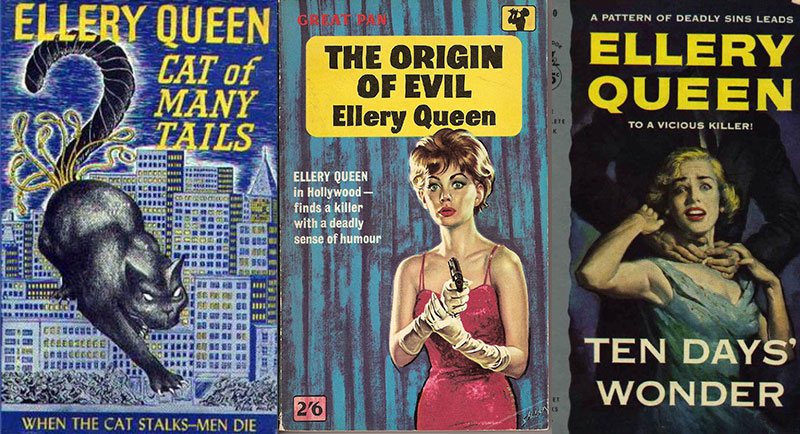

Perhaps Manny’s unrealized talents were more in the line of Herman Wouk than Herman Melville, but the Ellery Queen books are by no means an inferior job of writing. The period from 1947 to 1950, when the correspondence simply overflows with pent-up gall, is also when the powers of the bicephalic author were at their height. The best novels with Ellery Queen as lead character (Ten Days’ Wonder, Cat of Many Tails, and The Origin of Evil) were written during that fraught interval, and the technicalities involved in their construction are the point of departure for almost all the letters collected in Blood Relations.

Man to Dan July 5 1948

We were jealous of each other — each one in different ways for different reasons about different things. What began as friendly competition wound up as active and bitter hostility. The whole set-up was packed with dynamite, and our history as a “team” is a series of explosions. Neither of us has helped the situation, probably because at base we each have a foul and quivering sense of inferiority and in the other man we see the personification of what we unconsciously have feared might be, at least in specific aspects, a “superior.”

Dan to Man, Apr. 16 1948

We divided ourselves into rigid-boundaried “zones” just because our differences of opinion on basic matters of both plot and writing were so strong that we found it impossible to reconcile them either in principle or in practice. In the face of this, pleasing each other is pointless. We can only do, in our respective provinces, what pleases ourselves.

Man to Dan. Nov. 3 1948

Why am I writing to you? Why are you writing to me? We are two howling maniacs in a single cell, trying to tear each other to pieces. … We ought never to write a word to each other. We ought never to speak. I ought never to talk…

The only letter written outside the late 1940’s timeframe of Blood Relations is dated April, 1962, when Manny Lee was about to undergo heart surgery.

When I look back on my life it seems to me almost non-human in content, in the sense that to be human is to achieve, to rise above one self, to pull out of life a kind of victory against the odds. As we’ve both said on occasion, you and I are married to each other; and if more often than not it’s felt like a marriage made in hell — on both sides — there it is, and neither one of us can do anything about the past third of a century.

Bickering over plot points exposed a deep difference in worldviews as the source of the tension that was transformed into creative energy, which is what makes the story documented in Blood Relations transcend the cousins’ contribution to their century’s popular culture. Those tempted to add “Yeah, right, all the way to the bank” should take a look at:

Man to Dan, Feb 24 1950

I have slowly been succumbing to a sort of paralysis of the will which finds me, to all extent and purposes, a dead man. Clinically, I am going through what they call a “depression.” It’s too much, too much for me. I’m taking the fight elsewhere, calling for reinforcements. In a way, it’s a surrender, in a more important way, it’s a strategic turn of the battle.

Tell me what that is all about, if not the onset of clinical depression like the one chronicled in Darkness Visible by Manny’s Roxbury, Massachusetts, neighbor and friend, William Styron. “I think my father was the unhappiest man I ever met,” Lee’s son has said. Adds his sister: “He had this big thing for suffering, the Jewish disease.”

During the 1950’s and into the 1960’s, the collaboration began to wind down as Manny struggled to overcome a case of severe and prolonged writer’s block. Both Goodrich and Nevins, however, seem reluctant to describe how this condition affected him and how he spent his final years while cousin Fred looked after the family business.

By then, Ellery Queen was sufficiently established as a brand for the cousins to license the byline to other writers in their agent’s stable. Title page apart, Ellery is absent from some 30 or so of the paperbacks published under his name — the cousins had no hand in their authorship. However, several late “canonical” novels in which the Ellery character is featured were worked up from Fred’s outline by other writers while Manny and Fred edited their work.

Was it just the money that led Manny Lee to prolong his involvement with the character right up until his death in 1971, even though failing health could have given him an easy out? Ellery Queen may be largely forgotten by a reading public that probably wouldn’t think much of the books even if they had the chance to read them, but because of the iconic status the character achieved, the corpse in the drawing room may have a twitch or two left in him yet. •