Willow Pape is the bane of my existence. When I see her at Lif Club in Miami, I get anxious. There will be conflict. She once told me I should slip into something more comfortable like a coma. She continually works against me as I climb the ladder upward toward A-list stardom. On my best days, I roll my eyes at her. On my worst, my publicists spread rumors about her on social media. Being complicit in this process is the trouble with chasing fame.

I should have known better than to get caught up in the business of gaming. The premise of Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, a game available for mobile devices, rests on the idea that celebrity is itself labor. The only end goal is to become the #1 celebrity, which requires going to openings and making appearances, strategic and public dating, modeling, acting, and networking. The game requires the player to do everything and anything in order to become #1 (especially if they invest real life dollars to purchase “energy” and “currency” to buy outfits, furnishings, cars, private jets). Despite being a game, it’s a bleak commentary on the nature of celebrity in the 21st century.

I spent far too much of my time invested in the outcome. I was wrapped up in the pleasure of possibility and living vicariously through an avatar with so much access to fashion, travel, and celebrity connections. The ease in which I was able to slip into this world that promised me (even virtually) fame, fortune, and opportunity was frightening. I found myself lightly structuring my time around “jobs” and “hangouts.” As a media scholar, I knew better. But the attraction of Hollywood glamour, particularly the potential of making the A-list and “beating” the Hollywood game (with a certain level of ethical gameplay) was too much. That lure was definitely in the ether as I sat down to watch Nicolas Winding Refn’s new film, The Neon Demon.

It is not revolutionary to declare that the entertainment industrial complex — music, television, film, digital/social media — sucks. Articles about exploitation and alienation abound. Movies have moved from one-off spectacles to franchises, to now universes with the attempts of pulling in a global audience. Pop stars like Ariana Grande, Taylor Swift, and even Kanye West rely on a cadre of writers to execute their “artistic vision.” We can also find countless examples of the “problematic” nature of these industries — concerns over body image, exploited labor, and increased surveillance (our access to celebrities via social media). Celebrity has become a commodity in and of itself, something that must be attained or else as individuals we might become forgotten in the mess of Facebook posts, YouTube vlogs, Tumblr feeds, tweets, and Instagrammed selfies. But at the same time as fame and notoriety are to be desired, those who obtain and attempt to commodify their own celebrity are maligned. All of the Kardashians have made it work for them and yet are considered parasites by many bloggers and Jezebel commentators.

With everything indicating that supporting these industries perpetuates the above problems and entering into these arenas often means a life of rejection, criticism, and alienation, the question becomes: Why the hell would anybody willingly submit themselves to the objectification, the exploitation, and the criticism?

Plenty of films have explored the topic of celebrity. All about Eve, Limelight, Sunset Boulevard, Celebrity, Showgirls, Soapdish, and Boogie Nights feature narratives of people past their prime and struggling with their forced retirements. Waiting on the margins are their replacements: younger versions ready and willing to do anything to succeed. The themes are clear — popular culture industries (film, television, music, fashion) will chew you up and spit you out.

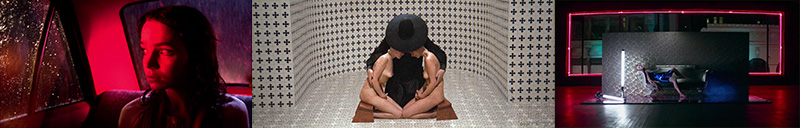

The Neon Demon perverts these old tropes. The film, directed by cult favorite filmmaker Nicolas Winding Refn, stars Elle Fanning as an aspiring model, Jesse (pronounced as Jess-ie, emphasizing her youth). We gather through context clues she’s a runaway of some sort, as she’s 16 and staying in a shady motel run by ne’er-do-wells and rapists. When asked about her parents, she says “they’re not around anymore,” a vague answer that could mean death (possibly murder) and/or estrangement. She forges their name (a practiced skill as she’s shown tracing from memory prior to placing pen to paper) on parental release forms and is encouraged to lie about her age by her representation. Saying she’s 19 will open up possibilities and according to her agent despite looking far younger, “people will believe what you tell them.” Jesse immediately barges her way into the modeling world — booking an agent, a high-profile photographer to shoot test photos, and the closing spot on a runway show with a major designer.

If this were a romantic comedy, this might lead one to believe we’re approaching peak American Dream narrative: that all will end well for Jesse who believed in herself and worked hard to gain entry into the industry. But Refn is Danish and instead provides a narrative about consumption — the metaphorical AND literal meal made of Jesse.

When Refn announced he was making a film about women with an all-female lead cast, it was an emotional mixed bag. On one hand, high fives for more films able to pass the lowest of low standards, the Bechdel Test. On the other, one of the last women Refn wrote, in 2013’s Only God Forgives, was murdered and, when found, her son tore through her stomach and placed his hand in her womb. Fun AND Freudian.

Refn’s women are used often as a means to critique masculinity/violence. Most are one-dimensional — victims, sexual objects, and overbearing mothers. There is no pleasure in their victimization, and part of his films’ purpose is to explore breaking points. His films are relatively banal until an explosive act of violence. Despite sources like Variety referring to his style as “blood-drenched,” his films are remarkably anti-violent. Whereas a filmmaker like Tarantino racks up a high body count and does so with a sort of perverse pleasure in the ways bodies contort when impacted by bullets or which makes murder itself the punch line of a visual joke, Refn’s films typically include one or two highly impactful scenes. Refn has related his use of violence to sex, choosing to depict violent acts as a sort of orgasm, with building tension being the majority of the narrative. The audience feels tension through gazes and gestures as opposed to dialogue. Many of his films rely predominantly on silence with highly stylized cinematography and an electronic Cliff Martinez soundtrack — a sensory experience that overwhelms plot and narrative in order to provide a surreal yet exploitative experience. It’s almost as if Dario Argento and Alejandro Jodorowsky decided to co-direct something — weird, oddly compelling, and bloody.

The Neon Demon is a new venture in its focus on women’s breaking points. Jesse is a fresh-faced ingénue. She appears bewildered, naïve, leading those around her to think of her as helpless. She doesn’t seem to know any names in the field or read any of the cues marked “danger” (like when a photographer calls for a closed set to be alone with her, reminiscent of the scandals Terry Richardson has been involved with for the past few years). Yet, it is hard to believe that, in the 21st century, she is not Googling or aware of industry operations (even stereotypes), and there are points when she smiles, indicating something more is happening behind her wide, doll-like eyes. Though hazy, by the end we understand much of her naivety is a performance, one she’s aware makes her desirable and marketable as a model — assumed availability, malleability, and a willingness to please.

It is also these qualities that make her the object of envy and a strong competitor. What’s unique about the film is the fact that women are the primary figures — men barely talk in the film and what they say is often misogynistic bile (used to underscore the “truths” these industries depend upon). Refn imagines the men in this industry to be predators. The famous photographer who shoots Jesse’s test shots lingers his gaze upon her for an uncomfortable amount of time before asking her to undress (after, of course, confirming her age as 19, which we know and he probably assumes isn’t true). Knowing he is one of the best-known fashion photographers and can make or break her career, she makes the decision to disrobe. The famous fashion designer who chooses her for his fashion show delivers an eloquent speech regarding the nature of beauty, ending with “beauty isn’t everything; it’s the only thing,” a revision of the infamous quote attributed to UCLA football coach Red Saunders. This sentiment reaffirms the competitive spirit instilled in the models that vie for his and photographers’ attention. Fashion becomes a blood sport — ruthless, violent, hazardous.

The hotel manager for Jesse’s dive apartment takes advantage, economically and sexually, of all the teenage runaways looking to find fame. When a mountain lion breaks into Jesse’s room, he charges her for it. One night, he tries to break into her room and, when unsuccessful, Jesse listens in horror to the screams of the 13-year-old next door being raped. Even the “nice guy” she meets, a young photographer, decides to maintain a romantic relationship despite knowing her to be underage. He is also disposable for Jesse and the audience. When Jesse challenges the fashion industry’s standards, she dismisses him because she has BECOME the standard.

Jesse is promised stardom, which means everything and everybody is disposable as is she to the others in the industry. She is competition for other models who attempt to belittle and shame her. The world of fashion is a cutthroat one.

By the end, the industry consumes Jesse. After acknowledging her own rise to the top to her competitors, two models who have lost opportunities to work because of her “look” and a make-up artist who attempted to position herself as an ally and lover murder her. They carve Jesse’s body, eat her flesh, and bathe in her blood. For those Countess de Bathory fans out there, the message and metaphor of consumption are clear. In order to maintain relevancy, youth, fame, or beauty, one must be willing to destroy those who threaten their position.

What is perhaps the most frightening aspect of the film is not the stylized schlock of violence Refn is known for, the act of murder, or even the threads of predatory behavior throughout; rather, it’s the casual and matter-of-fact treatment of the industry. The sense of “of course this is what it’s like” (albeit a hint more hyperbolic) and the resignation that this is the way it has always been and will continue to be is what caused the unsettled feeling to penetrate my skin and sink into my bones. Because nothing happens. Nobody is punished for their part in Jesse’s murder and, as far as we see, nobody cares. Despite being the rising star of the fashion world, the body and face those women coveted didn’t matter. The world moved on and the industry continued its practices of emotional and physical violence.

It is assumed there will be more Jesses. More women will come to Hollywood looking to make their break. The story has been nearly as old as Hollywood itself. The discovery of the hot new look — at the soda shop (Lana Turner), the airport (Kate Moss), or the mall (Gisele Budchen) — is part of a myth that continues to circulate and has become even more pervasive with the expansion of social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, where individuals can gather an army of fans and demonstrate their marketability to industry executives. And this is in spite of the fact that these stars tend to have little to no lasting power and are rarely paid for their labor (unless they can find sponsorship deals or crowd-source opportunities).

The film reasserts a harsh strand of reality supported by countless stories. Jesse does not provide a reason for why she wants to break into this world or for why she thinks she will be one of the few to “make it.” Refn seems to suggest it is her sense of entitlement. She pursues fame because she deserves it. She genuinely believes in her beauty. She is prideful as she explains that women will carve their faces to appear more like her. While in a stranger’s house, she goes through closets and dresses in the owner’s clothes, puts on their makeup without a concern that she has no claim over items. She is not uncertain or nervous. Jesse believes everything is hers. And it is perhaps this narcissism that provides her downfall — her lack of conscience.

Perhaps, if I hadn’t deleted the game a week after watching The Neon Demon, Willow Pape may have been the one bathing in my blood. The last threshold before transcending to top celebrity was to gather reality star NeNe Leaks and fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld (both actual avatars in the game) and along with the Kardashian clan throw an orgiastic blood bath with a precocious, fresh-off-the-bus-from-the-Midwest starlet. I was able to opt out easily by deleting an app from my phone without much room for regret. None of those people were real (that anxiety was definitely real). But the lure of potential opportunities is what keeps us in any destructive romantic partnership, job, addiction. We hope things will get better or that by investing more time and energy we will come out of the scenario unscathed or better for the experience. The optimism ascribed to celebrity must be even more overwhelming with far more dehumanizing experiences than Willow Pape’s mild class- and slut-shaming insults.

The Neon Demon does not provide any resolution. This isn’t a film that poses as a form of consciousness-raising or activism. If anything, the narrative asserts casually, a frightening reality that makes women’s exploitation a norm, patriarchy all-consuming, and the hope of female collaboration within such a system impossible. It is, if anything, another warning to those who idolize celebrity for the fact they are celebrities who do nothing but contribute to a potentially dangerous narrative — of youth, discovery, and fame. As long as the promise of success, that cruel optimism, exists, ingénues will continue to flock. Predators, poverty, and pain are all part of the ongoing process toward becoming celebrity, a “somebody” in a world of nobodies. Refn only exposes the cult-like desire to be noticed and attempts to exorcise the demons of narcissism that fuel such desires. •