Marcel Duchamp was a Romantic artist. If this statement shocks you, you are not alone. When Duchamp turned a urinal upside down in 1917, signed it R. Mutt, and tried to display it in an art show, most people took it as a challenge to established norms of art in the name of what is modern, new, radical, 20th century. Romantic art, by contrast, stinks of the 19th century. It is burdened by its obsession with big subjects like Nature and God. The Romantic artist is the solitary genius gazing with a troubled heart at some sublime landscape, perhaps a towering and cloud-covered mountain peak. A Romantic artist has little interest in urinals.

- “Dancing Around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Duchamp”. Through January 21, 2013. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

Calling Marcel Duchamp a Romantic is further complicated by the fact that it has never been easy to give a thumbnail definition of Romanticism. Baudelaire once said, “Romanticism is precisely situated neither in choice of subject nor exact truth, but in the way of feeling.” But what is the Romantic way of feeling? Is it big feelings? Hard-to-explain feelings? It is fine for Baudelaire to talk about feelings, but feelings can be notoriously difficult to pin down.

A quote from Clement Greenberg can be helpful in understanding Romanticism. Greenberg was no fan of Romanticism; he found it silly and self-indulgent. But he was a perceptive man. In one of his essays, “Towards a Newer Laocoon,” Greenberg tried to explain what was going on in Romantic painting of the late 19th century. He wrote:

The painted picture occurs in blank, indeterminate space; it just happens to be on a square of canvas and inside a frame. It might just as well have been breathed on air or formed out of plasma. It tries to be something you imagine rather than see…. Everything contributes to the denial of the medium, as if the artist were ashamed to admit that he had actually painted his picture instead of dreaming it forth.

Greenberg meant this an insult. Greenberg thought that painting should revel in the sensuous qualities of paint, not evaporate into a dream world. But the true Romantic accepts the charge of denying his medium. Romanticism is an expression of the ineffable — be that God, or the feeling of being alive, or the mystery of the fact that language conveys meaning. Sometimes Romantics simply want to convey the feeling that no matter how much we say or show we have always missed something. What Greenberg says here about Romantics is thus extremely perceptive. He says that some Romantics of the 19th century were making paintings, but that they painted as if they wanted to deny the medium of painting even while they were using that medium. They painted, Greenberg says with a sneer, as if they would rather have dreamed the picture forth.

That is true. Romantics have always been ambivalent, even embarrassed, about the medium. They use painting or sculpture or writing as a tool to convey feelings that otherwise transcend whatever medium is being used. Often the Romantic artist would prefer to get rid of the medium altogether. But then, how to make a painting without painting? How to make a work without a medium?

“The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” (The Large Glass), 1915-23.

Let’s look at one of Marcel Duchamp’s most famous works of art in order to find out. Duchamp worked on his Large Glass: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even for about ten years. The work is mostly composed of two large pieces of glass held in a metal frame. Duchamp painted directly on to the glass. He liked the look and feel of the glass mostly because it wasn’t canvas and he had already given up traditional painting by that time. The top section of the glass contains the bride, though she doesn’t really look like a bride. The bottom section contains the bachelors, nine of them. The bachelors are being moved around by a large chocolate grinder to which they are attached. None of these facts are deeply helpful for understanding this work of art, nor are they meant to be. Duchamp’s most famous single comment about The Large Glass is that it is a “hilarious picture.” As to the last word in the title of the work, “even,” Duchamp commented, “words interested me; and the bringing together of words to which I added a comma and ‘even’, an adverb which makes no sense, since it relates to nothing in the picture or the title.”

The companion piece to The Large Glass is Duchamp’s Green Box. The Green Box is a green box filled with a bunch of paper. On the paper are notes about measurements and speculations about the fourth dimension. “What we were interested in at the time,” Duchamp explained in an interview with Pierre Cabanne, “was the fourth dimension. In the Green Box there are heaps of notes on the fourth dimension.” It is not entirely clear what the forth dimension has to do with The Large Glass, except that Duchamp was inspired by mathematical concepts that he, admittedly, barely understood. He liked the idea that an object on three dimensions can project an “unseen” shadow just like an object in two dimensions can project a three-dimensional shadow. The fourth dimension is thus the unseen, the mysterious and, perhaps, unknowable aspect of all objects. He wasn’t trying to produce a scientific theory about dimensions. He was playing with scientific ideas and terminology to produce Romantic feelings. The Large Glass is not meant to be understood intellectually. Neither The Large Glass nor the Green Box translate into anything else. One of the things Duchamp hated about painting was its sensual quality, what Duchamp often called “retinal.” He didn’t want to make works of art that were to be looked at and interpreted visually. Duchamp didn’t think that art should produce an aesthetic experience, nor did he think it should produce an intellectual experience. Is there anything left to art when you remove both? For the Romantic there is. The more you deemphasize the medium, the closer you get to the inexpressible feeling that can never fully be captured by aesthetic or intellectual experience.

There is one further aspect of The Large Glass that we should mention. The glass is heavily cracked. This happened by accident when the work was being moved from one museum to another. When Duchamp saw the cracks, he was impressed. He called the cracks “perfect.” He was open to chance in his work. He once said (in the aforementioned interview with Pierre Cabanne), “pure chance interested me as a way of going against logical reality: To put something on a canvas, on a bit of paper, to associate the idea of a perpendicular thread a meter long falling from the height of one meter onto a horizontal plane, making its own deformation.” This is a Romantic thing to say and do. Since every work of Romantic art is an attempt to express the forces of nature, the divine, or the sublime, the element of chance becomes a way for those chaotic forces to produce real effects in the work of art. Letting a thread fall from the height of one meter onto a horizontal plane is a way of abandoning the art process to higher forces.

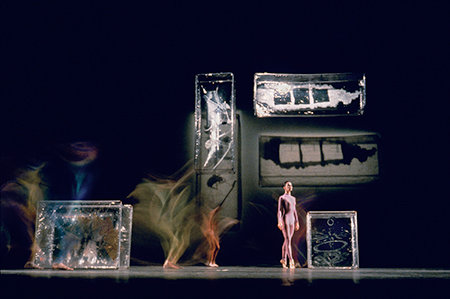

Dancer Carolyn Brown in Walkaround Time, 1968. Choreography by Merce Cunningham, American, 1919-2009. Stage set and costumes by Jasper Johns, American, b. 1930. Photograph © 1972 by James Klosty.

Many of the artists influenced by Marcel Duchamp were explicitly affected by his Romantic experiments in chance and accident. There is a show on now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art called Dancing Around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Duchamp. John Cage is the composer who, most notoriously, composed a musical piece that consists entirely of four minutes and 33 seconds of silence. The “sound” and “content” of the piece are all the incidental noises — the shifting of the audience, noises from outside the performance space — that inevitably occur over the four and a half minutes. Chance is, literally, making the piece. Cage also famously composed by means of random sequences generated by the classical Chinese text, the I Ching. The choreographer Merce Cunningham used these same procedures in developing many of his dances. Cunningham trained his dancers in various sets of movement. He would then arrange these sets according to random throws of the dice the day of the performance. Cunningham made this work explicitly as a reference to Duchamp.

John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and Robert Rauschenberg outside Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London during the 1964 world tour of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company.

Robert Rauschenberg made a series of all-white paintings after meeting Cage and Cunningham and seeing the work they were doing in the early 1950s. Cage called Rauschenberg’s white paintings “landing strips,” meaning that they were like little airports for light and shadow and dust to chance upon. They are to painting what Cage’s silence composition is to sound. The work of art becomes an opportunity for chance events to happen beyond the artist’s control. Versions of this idea became a major theme in 20th century art and it was Duchamp who opened up this territory.

You could say, then, that Duchamp was the bridge from the Romanticism of the late 19th century to that of the 20th. He made Modernism safe for Romantics. He was carrying the Romantic legacy forward through the death of painting (or other media) into a new world. Duchamp said, “if you wish, my art would be that of living: each second, each breath is a work which is inscribed nowhere, which is neither visual nor cerebral.” Or, as Greenberg put it about the Romantics, “denial of the medium.”

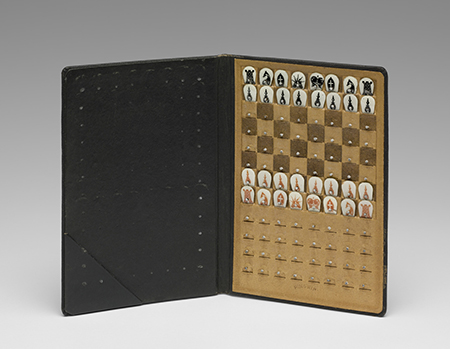

Pocket Chess Set, 1943. Marcel Duchamp

For 20 years at the end of his life, Duchamp did little more than play chess as his primary artistic activity. This was not done out of some nihilistic desire to destroy art. Duchamp did it because he was trying to find a medium completely untainted by aesthetics. No medium at all, just the Absolute. Secretly, while he told everyone that he was done with art and only playing chess, Duchamp was working on his last great creation. He called it Étant donnés. Étant donnés is a peephole through a wooden door. Behind the door is a park where lays a corpse. The corpse is naked and splayed out so that one looks directly at the genitals of the naked, dead woman. Among other things, it is the work of an artist who, as Greenberg puts it, is ashamed that he is producing art. For the Romantic artist, being ashamed is a good thing. It means that you refuse to confuse the tool with the truth. Amusingly, the Romantic art of shame has proved far more resilient than any of the forms of art that Clement Greenberg championed, like Abstract Expressionism. 100 years on and we are still dancing around the bride. • 4 December 2012