Rudolfo Botelho must have been about 65, perhaps younger, though of course to a 15 year old he appeared ancient. His white moustache bristled on an otherwise mild beige-skinned face. You didn’t much notice his small size; it was always the moustache you saw. And the twinkle — there was the twinkle. I lived in Shanghai, 15 years old in 1948, a Eurasian child of an Italian-Dutch-Indonesian father and Chinese mother. My parents knew him back in the golden days of Shanghai’s roaring ‘20s like those in America. I met him when he became the accompanist for the choir at St. Columban’s, a church run by Irish priests.

He took to me, and decided one-handedly that I was to be his protégée, to become someone like Dorothy Parker, frequently featured in The New Yorker magazine. I had never heard of her and had never seen an issue of The New Yorker, either. Moreover, he would show me a thing or two about living. I marvel, decades later in my own old age, that my parents trusted him to take me out one evening. He lingered to chat a while, addressing my father, Leopoldo, as Poldo, made a joke about the fine times they had together, as my father laughed. He said to my mother, “I will never forget you fox trotting on the Palace dance floor. Best-looking woman in the place.” He had moved in the coterie of my father’s friends at the Canidrome, the track that ran two dogs from our kennels. It was all about champagne picnics and excursions to Macao and Hong Kong and Italian club events and the businessmen’s club at the Bund. I had heard about those famous good times, which were long gone by the time the Second World War broke out. Before that major war, there was the matter of the 1937 Sino-Japanese conflict, when Japan invaded Chinese territory.

And then, in 1948, both Shanghai’s foreign and Chinese citizens were nervously awaiting the invasion of Mao Tse-tung’s Communist army. Many foreigners stayed on, insisting that China always needed her businessmen. My father was one of those, though now I realize that he was afraid of striking out in Italy on tight resources and poor health. He had been born in China; Italy, the land of his father, was safer as an unknown country than as reality. Then there was my mother, an old-fashioned lady with bound feet. How was she to fare with little English, no Italian, and when every step with her crippled feet caused pain? My sister Maria, older by 11 years, held a job with Caltex, which would last as long as foreign businesses were expected to stay before the next upheavel. She was brave and daring, ready to travel abroad if our father found his resolve. And I, unfurled yet in social skills every teenager was supposed to own, and with nowhere to use them had I any, became an avid pinochle and poker dice player opposite my big sister. When the Japanese occupation army marched out of Shanghai in 1945 and American films came back, the entire family went to the Roxy Cinema to see The Sweetheart of Sigma Chi, something about college fraternities and girlfriends. I was thrilled, but Maria said that Hollywood must have thought we were so starved for entertainment they could send us silent movies.

What did I know? Not much. Maria taught me to dance, a stilted two-step that didn’t help when the jitterbug hit Shanghai along with the American G.I.s and sailors.

Bottles added to my education.

I am not certain if he told my parents where he planned to take me that evening, but they saw us off equably enough though perhaps my mother, deferring to my father, was not so sanguine. Maria thought I needed to see what life was about outside our neighborhood.

Bottles settled us in a rickshaw, which pulled us to the first of his favorite cafés. Downtown Shanghai still bustled with commerce, though compared to the Good Old Days (according to my parents), the area was nearly lifeless. To me, it was downright hectic after the Japanese army occupation. What did I know about working traffic lights and traffic cops and staying on the right side of the street? In my opinion, everything moved pretty well. Of course, the beggars had grown in number — babies in arms and some of the adults missing a limb or wearing terrible sores. Even I was aware that the children were sometimes rented out by a beggar king, who lived in a mansion somewhere in town.

And so our rickshaw wove us through this swarm of humanity and deposited us at the Jolly Café, an establishment operated by a Russian émigré. Shanghai harbored thousands of refugees from the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. The city also had a huge population of Jewish refugees from Hitler. And before WWII Shanghai had British, French, American and the odd Dutch businessmen contributing to its prosperity. They were fewer now, though the Italian Club sputtered along on its remaining members. My grandfather had come to China in the 1870s with a diplomatic envoy. Dad became an importer-exporter and owned a freighter which was sunk to the bottom of the Whangpo River by Japanese bombers.

How ancient that history!

The women who dropped in and out of the Jolly Café were Russian refugees, or White Russians, as they were known in Shanghai. I knew all about the history of how they crossed Siberia on foot or by train into Manchuria and down into Shanghai. So much of it formed part of the threads woven into my childhood, liable to come out of my mouth anytime in a phrase in Russian, or in Portuguese. I cursed right along with the Japanese kids who lived next door. Chinese I could rattle off in the Shanghai dialect, though I could not read it. As a Eurasian child in an international community, there was no sense in being sent to Chinese-language school. The only language I had no acquaintance with was Italian, my family’s nationality.

The Russian ladies made much of Bottles, their nickname for him, bought him vodka and me lemonade, kissed his head, told him the latest in their ongoing sad stories, while he steadily drank vodka. Life was hard for these girls torn from their childhoods in the exodus from Russia. They had had no education, sketchy family upbringing, and most made an existence out of consorting with American soldiers and sailors. And those were not going to stay around when the Communists came.

The girls listened earnestly as he dispensed advice. To one petite blonde girl, he said he could place the child she was about to have with a good family, a Chinese one. Or what? she asked tearfully. Or, my dear, he said gently, I can arrange an abortion.

At this, I recall nodding sagely and handing her my napkin for her wet face. Maria would have been proud. I had not yet had a date with a boy; eligible boys were in short supply and my education so far at a school run by nuns left a massive gap in my knowledge of the human anatomy. For years, I thought everyone had two livers. The meaning of “abortion” was not quite clear in my head but if Bottles recommended it, abortion was the solution to her problem. There were by then so many interesting facts to add to my life’s book of knowledge they must have looked, in colors, a palette to blind the eye.

Bottles knew what to do about everything. He knew everyone. His own family consisted of a son who lived in an apartment in a nice section of town. There was a mysterious wife living in Austria who had been a trapeze performer. Like many Portuguese citizens who drifted north from the Portuguese colony of Macau, he had settled in Shanghai. He played piano at various cabarets around town, but there weren’t many of those left in the jittery city.

One day he took me to his attic flat and set me at his piano keyboard. There was scant light to see by, for the only window was the skylight set over the wrong side of the room. Piles of books and sheet music on the floor leaned this way and that and dust coated everything but the piano keyboard. All of a sudden, I was shy with him and avoided glancing at his bed — a cot, really. As for the lessons, I think I was expected to demonstrate instant genius — become a Dorothy Parker of the piano. He became impatient. After a half hour he halted my finger exercises and announced we were going to a show. I was excited. Shows of any kind were a rare treat. Actually, I had never been to one. The Sweetheat of Sigma Chi did not count.

What kind of show was it to be?

Back downtown, we entered the Starlight Café. It fronted Nanking Road, a main thoroughfare of the city. The back of it, Ah the back of it, Bottles said. Shall we? he asked the Russian café owner and his wife. They smiled and nodded, and waved us out to the backyard. Bottles began to move chairs to the fence.

We are now going to be rabbits, he told me.

Rabbits?

He sat down and gestured me toward the other, then at the wooden fence. I saw that the gaps between the boards had been whittled wider with a knife. I peeked through the gaps. About 100 feet beyond a stage was lit up around the edges. People, American servicemen in army and navy uniforms, were arriving to sit on benches amid laughter and talk. A band, unseen until now, struck up. The sound of it was a bit strange, uncertain and a bit off-key. Bottles was smiling gleefully.

Women came dancing out on the stage, wearing shorts and halter tops. I recognized one of the girls as Bottles’s friend at another café we had visited. The audience clapped and whistled.

Then it roared and screamed as the last woman skipped out, a lovely blonde shimmering with sequins like stars down from the sky. A film actress?

I was enchanted with the spectacle I was watching with one eye, then the other. I had never seen anything like this, which I now know as an adult was lame because of the uncertain band music and amateur moves of the chorus line. The microphone squealed during the actress’ patter and songs. She told jokes I didn’t quite understand but, like the servicemen, I didn’t care and loved it all. I think I stopped breathing.

Bottles was immensely pleased with himself, it seemed to me, as the rickshaw coolie pulled us home. I gave my parents a jumbled report about rabbits and fences and movie stars. My mother asked, to make sure, And the soldiers were on the other side of the fence? She looked very stern for all her tiny size; whenever she was upset her little bound feet planted themselves on the floor emphatically. That always meant business for me, but she was of a time that taught women to be submissive to their men though stern with their children.

I had so much time to get into mischief and she worried about that. Before I landed in the current school I had been enrolled, when politics permitted, in a Russian school taught by Irish nuns, a French convent, an American school, and finally the Loretto School taught by American nuns. The elementary school I attended for a few months before the war ended was run by two former secretaries of Portuguese nationality who, when the GIs took over the city, worked as hula dancers in a nightclub.

My aggregate months of formal schooling totaled five years, if even that.

Bottles taught me to read music on off days at St. Columban’s. One song, “For All We Know,” had a pretty tune and sickly romantic lyrics. Neither of us thought it odd that we were playing and singing pop songs in a church. Or, if Bottles did, he didn’t much care. If Father Murphy, who had a sense of humor, had heard us he would have decided to let it alone.

But I shone at singing for masses, for the reason no one else in the choir had as high-pitched a voice as mine. It was nominally a soprano, an untutored reed that rose high above the humdrum altos. I know now it was pretty shrill and I got away with it because there wasn’t another soprano in the bunch. The mostly Chinese congregation didn’t seem to mind, or perhaps they were distracted and fascinated by Father Hughes’ sermon in a sort of Mandarin that my mother said sounded charming though incomprehensible. Bottles took it all easily, sermon and choir. If he was ever upset he would utter a grumbling La Vache! and that would be the end of it.

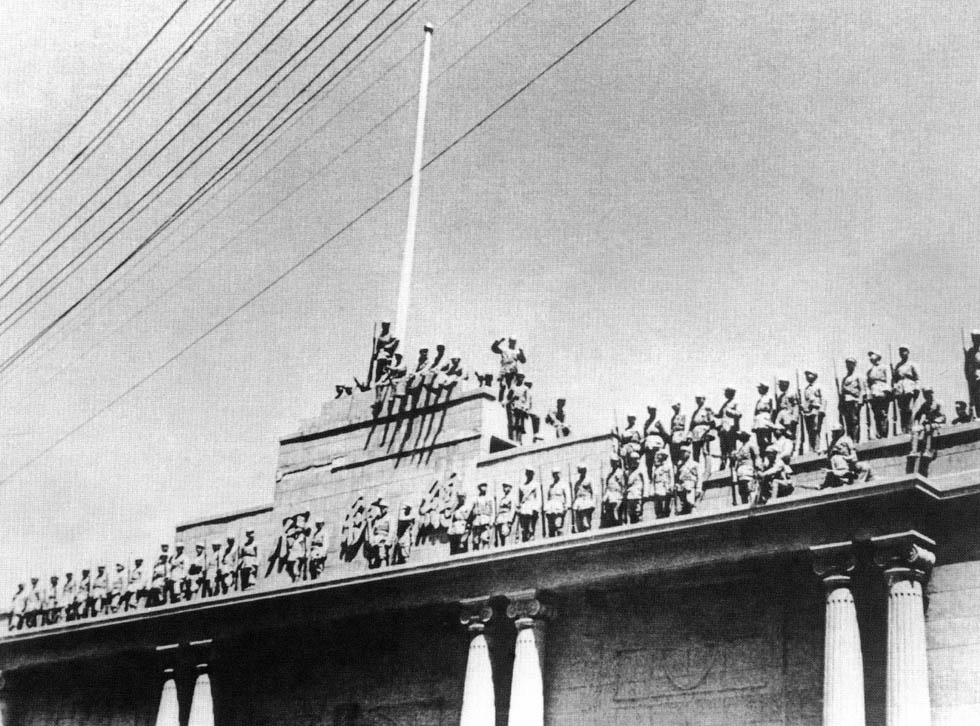

In the spring of 1949 the residents of Shanghai began hearing gunfire from the northwest horizon; the Communists on the north shore of the Yangtze River were sending their artillery fire into any kind of river traffic passing through. A British ship, the frigate HMS Amethyst, took fire and sank. A clear sign of change from colonial times. Had that happened 50 years ago, Great Britain would have wasted not a moment exacting punishment upon China.

I received no more piano lessons. Quietly, Bottles began to pack. He did give me an old copy of The New Yorker. It stayed in my possession, perused so much for mention (I found none) of Dorothy Parker the ink probably faded, until my family and I were exiled from China by the Communists. Before our release into the wilds occurred (as my writer’s mind now thinks of our exodus from China), I found myself facing the prospect of a communist firing squad. Bottles had receded to a memory of good times, comparatively viewed, in my adolescence.

Three years after Mao Tse-tung’s army marched into Shanghai in April 1949 and the extermination of capitalists began, where Chinese possessing any kind of assets began leaping from tall buildings, Maria and I visited the police station to apply for our exit visas. Life under the regime had become so unbearable that my father at last recognized the inevitable. We had to leave China. By then, it also became clear that Maria was to be family head, after his two heart attacks.

And so Maria asked the police for our permits. Openly sneering, the man in the exit visa office examined our four passports and asked how our mother had managed to become an Italian citizen. Maria explained that the entire family had been registered at the Italian consulate. The atmosphere in this place was hostile, the uniformed men here staring at us and laughing at remarks they made to one another. In three years under Communist rule I had learned to show no emotion, to ignore taunts in the streets by children about being products of a foreign devil and Chinese whore. They had the racial part correct. There was never a Chinese man and foreign woman combination that I hadn’t heard of.

The visa application process took an ominous turn.

The man told us to wait, which we did for three hours sitting on a splintery bench.

We did not speak, but we sat very close to each other. Finally, he looked over at us and told us to return the next morning at 7 a.m. Maria and I went home knowing worse was to come.

The next morning we sat in a room furnished with a table, chairs, and a large picture of Mao on the wall. The officer behind the desk told us to fill in and then sign the documents he turned toward us. Maria asked what they were about. She couldn’t read Chinese either.

He told us they were confessions to espionage. We had been caught spying for the United States and if we did not sign, we would be executed by firing squad.

I cannot forget how hard my heart beat then. Maria said we couldn’t know what we were to sign, and anyway the charge was nonsense. The man said it was a questionnaire and since we were obviously ignorant people he would call up an interpreter and to come back tomorrow at 7 a.m.

It didn’t matter if the charge of spying for America was ridiculous; they could say or do anything they wished, as was the threat of execution for my deeds, real enough at the time while Chinese citizens were being pulled off the streets and shot in the Shanghai Race Course. After a week of our reporting at 7 a.m. they told Maria she was no longer needed, and concentrated on me. I was 18 and I suppose they believed I would be easy prey. But my youth’s sense of injustice was outraged. I continued refusing to sign. To their demands for names of “collaborators” I told them there weren’t any. For six weeks I shuttled between stationhouse and home early each morning and late at night. We were Italian citizens but only partly immune from the new regime’s reforms, a situation laden, as my father judged, with peril. His actual words were “They can chop off our damned necks if they feel like it!”

In the middle of this I received a letter from Bottles asking how my family was faring. He was still in Macao and contemplated shipping off to Samar in the Philippines, where the government was placing refugees. He did not mention the word communist nor, obviously aware his letter might be opened before it reached me, how the rest of the world was regarding the occupation or what was being done about it — precisely the information my family wanted so badly to hear. My father said it was best I did not write back. The less mail being exchanged between outside ports and us the better.

The police began hauling in foreign nationals from all over the expatriate community, accusing them of misdeeds against the new government (“subversive” was a favorite term), confiscating their assets, then finally throwing them out of China. No foreigner was executed. That was one line they dared not cross.

And so we departed, armed with $50 and one suitcase each to forge a new life in Italy. By then Dad was dying. He spent our entire 33-day voyage on the Italian cargo ship, Sebastiano Caboto, in the sick bay. His only acquaintance with the country of his forebears must have been a painful blur to him, while Maria found ways for us to survive. That would be another story.

Before leaving Shanghai I received one more letter from Bottles. He wrote that he was still living in the relocation camp in Macau, missed his piano, and for me to remain strong and read everything in print. At the bottom of the letter he scrawled

read read

read

read

###

•