At the risk of being reductive (and I most assuredly am), there tend to be two types of male characters in Daniel Clowes’s comics: Socially maladjusted, marginalized misfits that are incapable of attaining anything resembling love, success or happiness (e.g. Dan Pussey, Mister Wilder in Ice Haven, the titular Wilson) and self-assured, bitter tough guys (or, more often, would-be tough guys) whose inner lives house just as much desperation and anxiety as the former (e.g. the lead character in Black Nylon, Joe Ames in Ice Haven, Andy in The Death Ray).

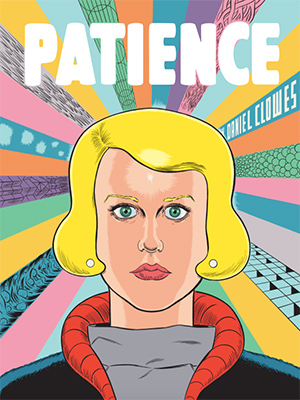

It’s mostly the latter that’s on display in Patience, Clowes’s latest graphic novel. What’s perhaps most surprising about the book, though, is how sincerely straightforward it is. Whereas Clowes has previously tended to view his protagonists with a critical (albeit occasionally sympathetic) eye, here we see him working with, to quote critic Ken Parille, “a full-on action hero” and indulging in what at first glance appears to be a conventional genre tale.

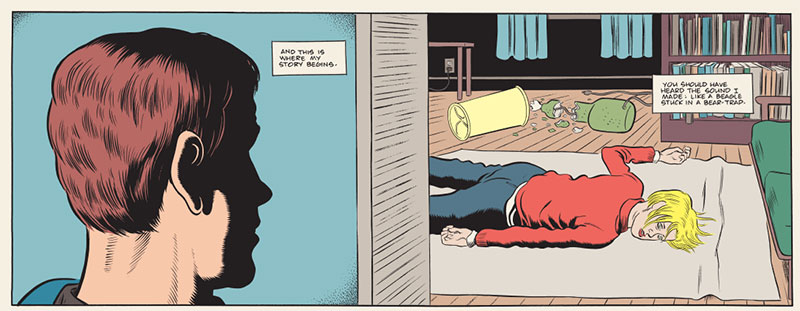

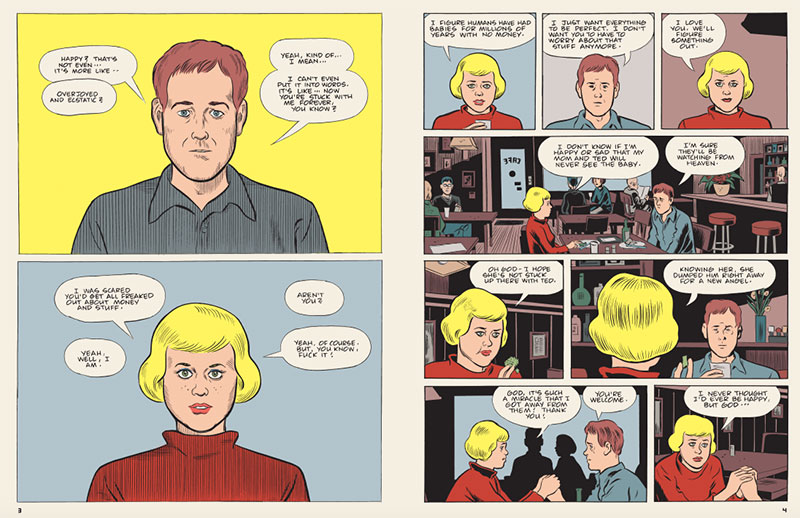

The hero in question is one Jack Barlow, who lives with his wife, the titular Patience. The couple is financially struggling but otherwise happy, and as the book begins they discover they’re about to have a child. Then, one day, Barlow comes home to find Patience dead, murdered by an unknown assailant.

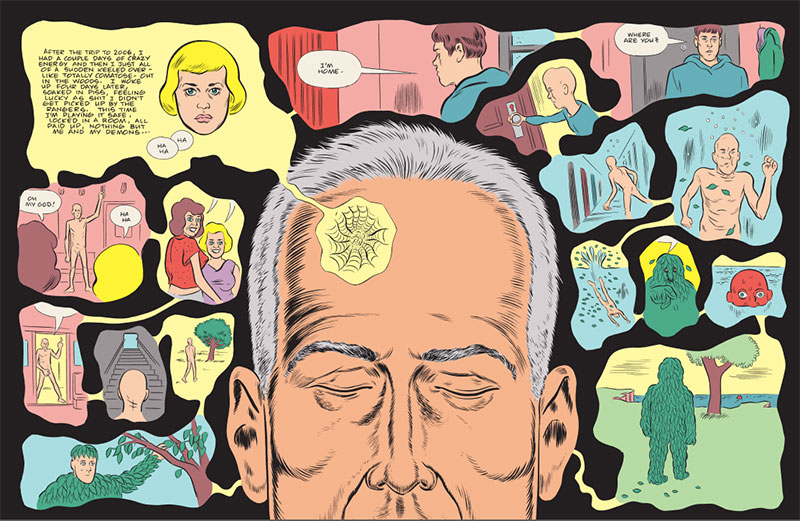

Fast forward several decades into the near future (2029 to be exact). Barlow has become an embittered and hardened Hammett-esque type whose life has entered a calcified stasis to the point where he’s seemingly unable to have a relationship with anyone, even a prostitute.

That prostitute, however, points him in the direction of a man who might possibly have discovered a way to travel through time. One thing then leads to another and very soon Barlow finds himself transported to the past on a mission to find and halt his wife’s killer.

As story hooks go, it’s pretty irresistible. How many of us have wanted at one point or another to go back in time — not to right historical wrongs or prevent genocide but merely to fix our own dumb mistakes and heal our deep-seated wounds? And to do so as a hard-boiled action hero? Sign me up.

And Clowes has always had a strong interest in detective stories. His first major character, Lloyd Llewellyn, was a detective, after all, and many of his subsequent graphic novels — Ice Haven, Like A Velvet Glove Cast in Iron, David Boring — have a mystery as their MacGuffin or hint at aspects of the genre.

So at it’s heart, Patience is a sci-fi whodunit, not unlike the kind of comics Clowes himself used to read as a child. In fact, in a large way, Patience feels like a love letter to some of his primary influences — artists like Curt Swan, Bob Powell, Steve Dikto, Jack Kamen, and Johnny Craig. Although more more detailed and sophisticated than its predecessors, Patience very much feels in league with the offbeat stories publishers like DC and EC used to publish in the 1950s and ‘60s.

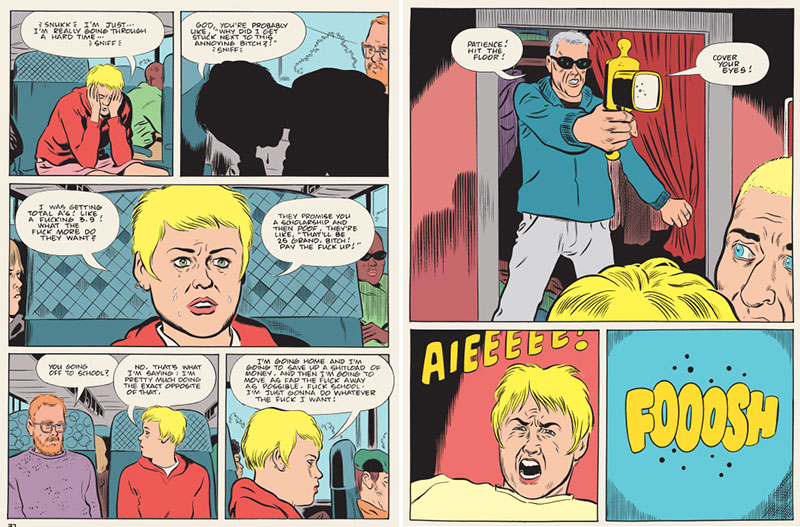

Perhaps that to some extent explains the comic’s seemingly earnest tone. Most of the book is narrated by Barlow and it can be difficult to ascertain what we, as readers, are supposed to make of him. When the book begins he’s already a bit of a sad sack, mired in anxiety over his budding family’s financial troubles, but as the story progresses he becomes downright monomaniacal, talking like a Mike Hammer redux (“Don’t call me an asshole again or I’ll pound your lumpy-ass face into oatmeal”) and inflicting a surprising amount of violence on various supporting cast members — some deserving, some not. Barlow’s hard-boiled narration feels like it’s constantly on the edge of parody, especially when he soliloquizes about his one true love (he refers to her as a “precious little angel” and an “innocent little girl,” which strikes me as full-on stalker speak). His behavior towards Patience turns from loving to paternalistic to creepily obsessive. And Clowes is too smart an artist to not be aware of this progression. Are we supposed to take Barlow seriously? The bittersweet ending seems to imply as much.

Part of the book’s problem lies with the character of Patience as well. Though we are given access to her inner thoughts, she still remains more idolized object than fully-rounded character. We only see her in her relationship with Barlow or other men (all of them nefarious or cruel), and her thoughts mostly revolve around trying not to freak out about this time-traveling weirdo seeming affecting her life. We see her having to drop out of college but never find out what she was studying or what her career goals were. We only get glimpses of her family life. While it’s clear that Barlow is the central character here, it would have been nice to have the object of his affection come off as a bit more nuanced. What’s on the page certainly wouldn’t pass the Bechdel Test.

Which is not to say that Patience is without merit. Clowes does hit some satisfying genre notes, such as when Barlow tries to enter a swank ‘80s nightclub. But Clowes’s art work might be the best thing about Patience. Having favored a looser, more cartoony style in books like Wilson and (to a lesser extent) Mister Wonderful, Clowes doubles down on a tighter, more realistic, more controlled rendering, one that often gives way to elaborate two-page vistas of a futuristic city or surreal, psychedelic visions (the result of too much time-traveling on Barlow’s part). These highly detailed sequences, decorated in flat, bright pastel colors that give the book a menacing “pop art” style. The result is some of his best and most assured art work to date.

Ultimately, though, I can’t quite figure out how much I’m supposed to read into Patience. Is there more to Barlow than meets the eye? What should I make of the fact that his time-traveling actions seem to hinder and hurt Patience as much as help? What about the fact that all of the women Barlow encounters, Patience included, look deceptively similar? Is Patience’s final decision a rebuke of some sort to Barlow? Or is it his bittersweet reward for having fulfilled his request and (spoiler) saved the girl? Is Patience a subversion of genre fiction or an unironic celebration of it? The book seems to hit at the former while professing the latter in a manner that’s just as frustrating as it is enticing. •

All images courtesy of ©Daniel Clowes.