Religion and spirituality are not subjects that have figured heavily into the world of American comics. When they have, traditionally, it’s been either in the form of evangelism (i.e. Jack Chick’s hardcore proselytizing pamphlets), straightforward adaptation (Picture Stories from the Bible and Robert Crumb’s by-the-numbers version of Genesis) or nose-thumbing iconoclasm (Winshluss’s In God We Trust being a recent example). Rare is the comic or cartoonist that attempts to grapple with issues of theology — or at least Western theology — in the modern world.

Not Chester Brown, though. While far from being the central focus of his bibliography, Brown has long been fascinated with exploring and questioning Christian doctrine, especially when it dovetails with sexuality. It’s a fascination that comes to a head in his latest work, Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus: Prostitution and Religious Obedience in the Bible.

Is some backstory in order? Then backstory you shall have. Brown came on the scene in 1983 with his self-published mini-comic Yummy Fur, a one-man anthology series (picked up by indie publisher Vortex Comics in 1986 and then Drawn and Quarterly in 1991) that initially combined a general horror with sex, body functions, death, and other taboo or generally icky topics with a decidedly surreal, deadpan sense of humor. (Case in point: Ed the Happy Clown, the central storyline in those early issues of Yummy Fur featured, among other things, a man who literally cannot stop defecating. [It turns out it’s because his anus is a doorway into another dimension in which . . . I better stop there.])

Feeling as though Ed had reached a proper conclusion and dissatisfied with his current surreal mode of storytelling, Brown segued to autobiography, first with the The Playboy, which detailed in the best cringe-worthy fashion his teenage masturbatory habits, and then I Never Liked You, arguably his masterwork, a heartrending tale of adolescence that is all the more wrenching in its absolute restraint and refusal to have its main character (i.e. Brown) display the smallest hint of emotion.

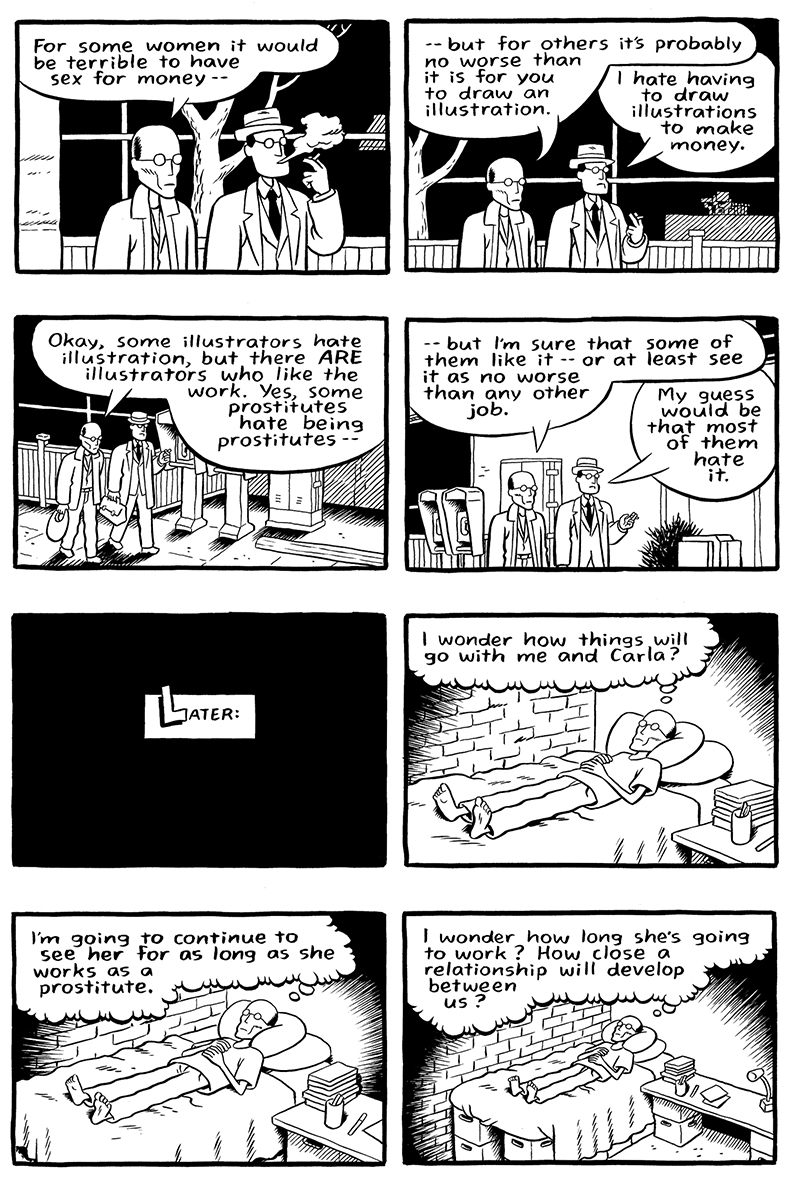

From there, Brown tackled historical fiction with Louis Riel, an account of the 19th-century Canadian resistance leader, and then delved back to autobiography again with Paying for It, a matter-of-fact recount of his adventures as a john in the world of prostitution (more on that in a moment).

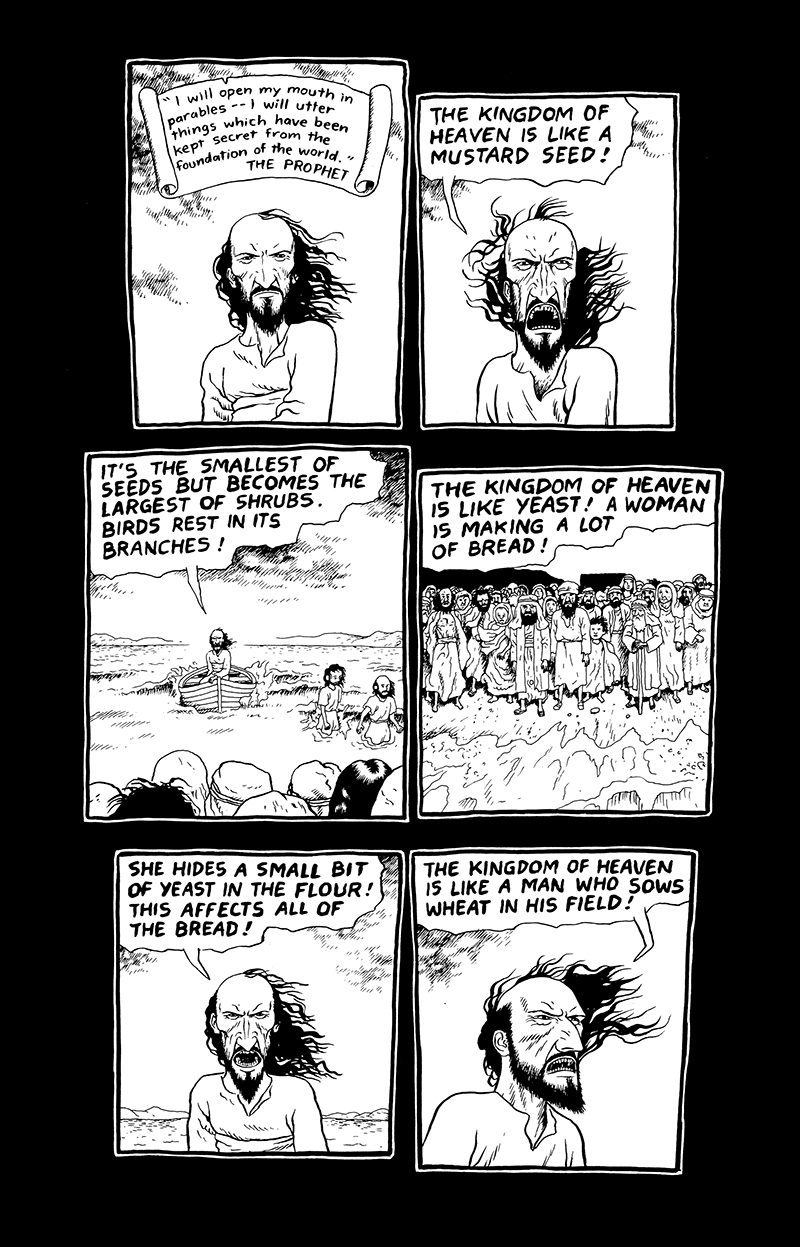

Throughout it all, however, Brown has always shown an interest in Christianity. Or rather, challenging basic assumptions about Christianity. In Yummy Fur and later in an abandoned follow-up series, Underwater, he made an ambitious (and eventually abandoned — the halls of comics are littered with abandoned Chester Brown projects) attempt at adapting the four Gospels, depicting Jesus in a slightly different manner each time — beatific blond holy man in one version, angry, balding radical in the other.

But the best hint of Brown’s offbeat take on spirituality can be found in “The Twin,” a short story collected in The Little Man compendium. An adaptation of a Gnostic text, “Twin” depicts a young Jesus meeting his “twin brother” (i.e. the holy spirit), and ends with the two kissing and then meshing into one being, the sacred and the profane combining to make a whole, newly self-aware person.

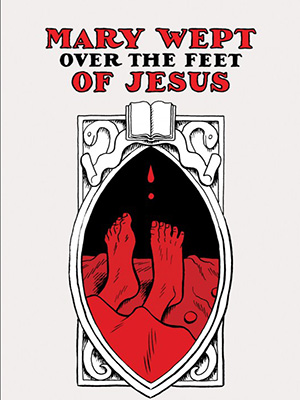

But it is in Mary Wept that Brown’s interest in Gnosticism, Biblical studies, and re-examination of traditional Christian doctrine comes to the fore. Designed to look like a little chapbook or pocket Bible, the cover image features a yoni or vulva-shaped center panel, the inset of which shows Jesus’s feet and a slow drip of liquid posed above exactly where, as critic Ng Suat Tong notes, the clitoris would be. Meanwhile, two phallic snake heads adorn the upper corners. While the imagery is subtle, it is also clear to the reader that we are a long way from Picture Stories from the Bible.

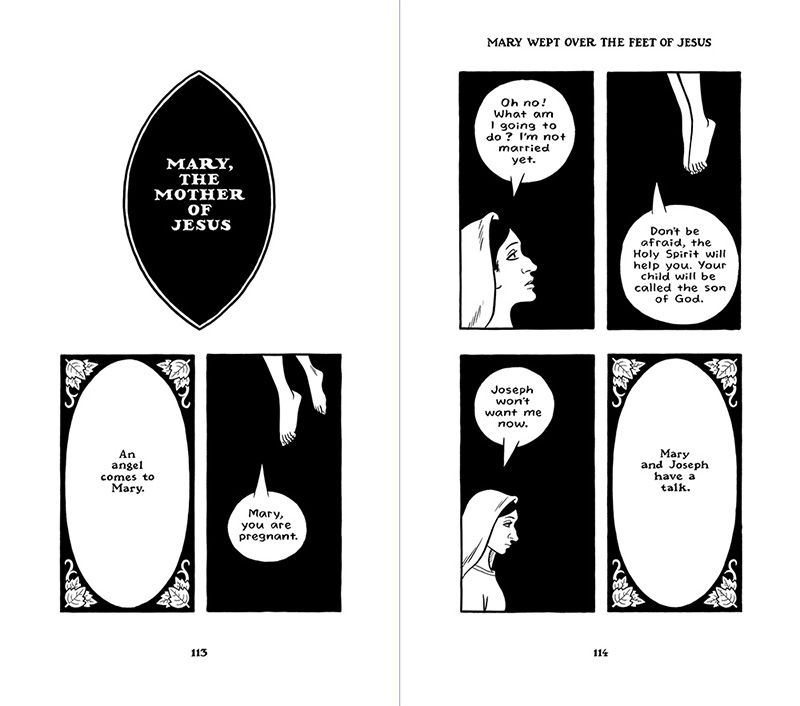

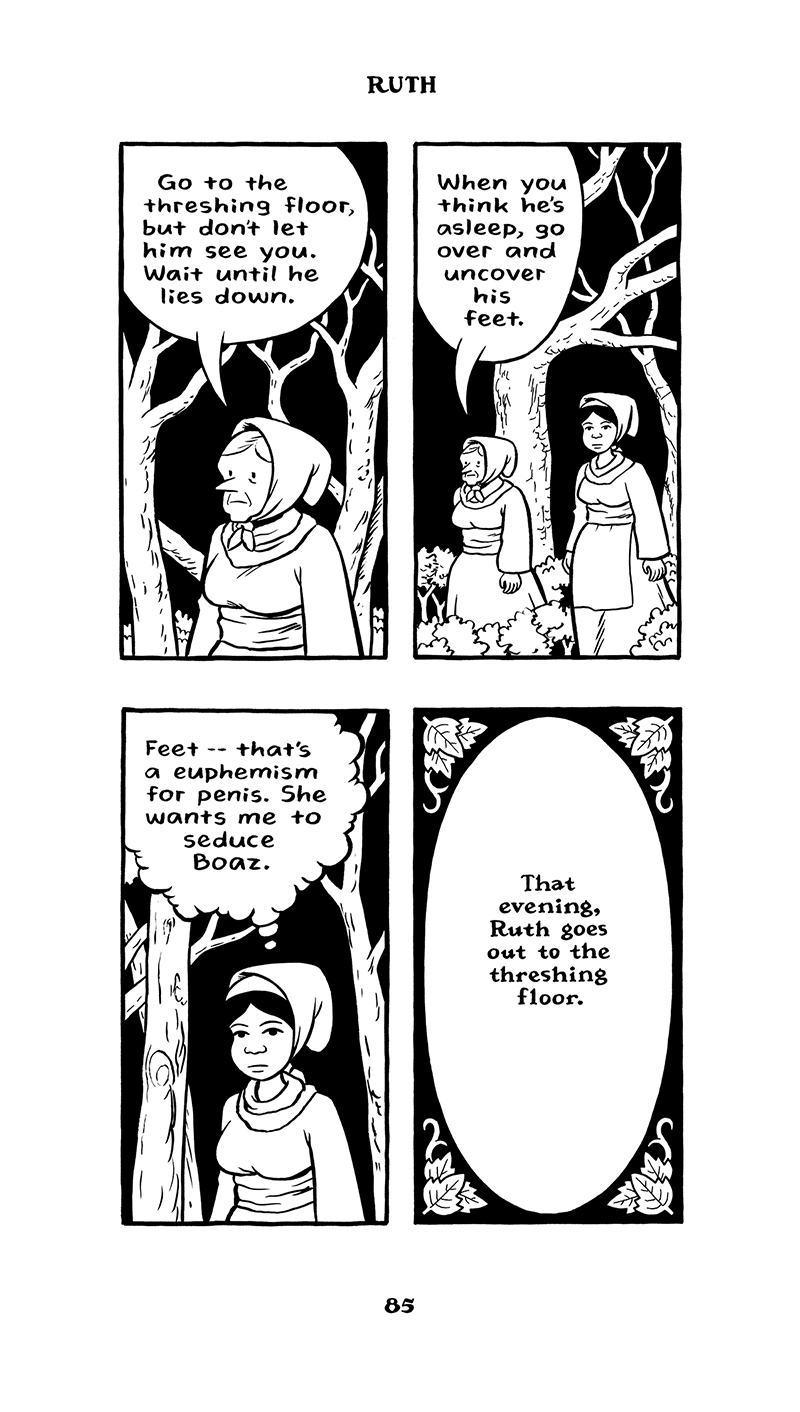

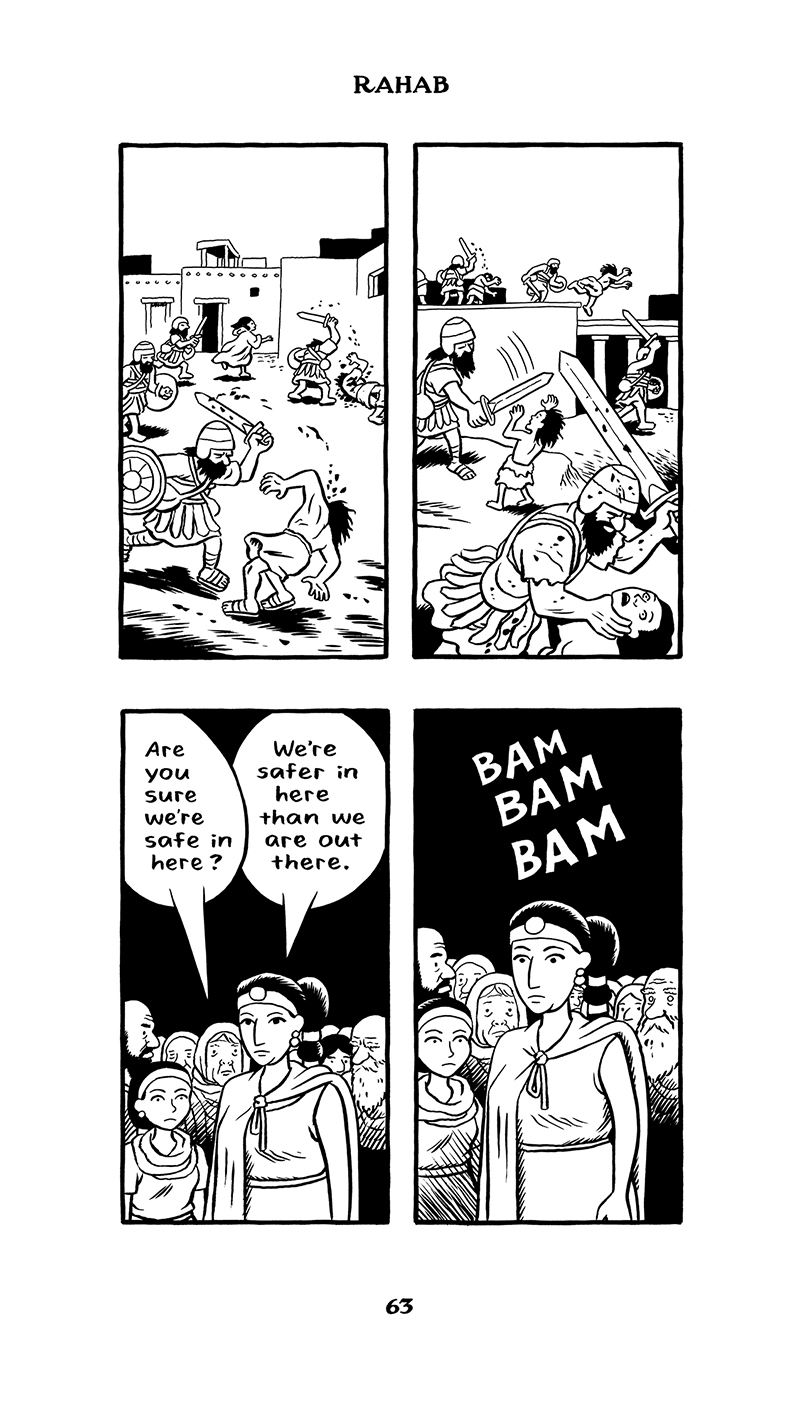

What we get instead are tweaked or in some cases heavily reimagined retellings of various Biblical stories, many of them involving women, mainly those who were prostitutes or engaged in some sort of quid pro quo sexual liaison. There’s Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and Bathsheba, before Brown gets around to the New Testament and Jesus’s mother Mary, as well as Mary of Bethany.

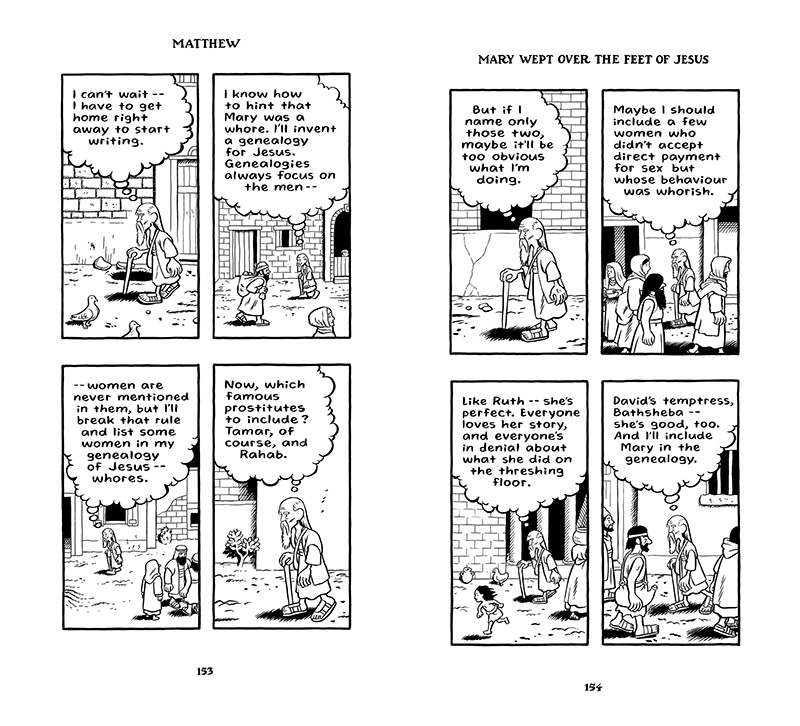

There’s a specific reason that Brown picks these women’s stories and not less overtly sexual Biblical figures like Judith. Influenced by the writings of the late scholar Jane Schaberg, Brown is specifically calling into question Mary’s virginal status. The theory goes like this: Most lineages in the Bible are patriarchal. Whoever wrote the Book of Matthew, however, took specific pains to highlight Mary’s lineage through these specific women. Why?

Schaberg opined that the author of Matthew was laying a subtle clue that Mary might have been raped or seduced and that Jesus was illegitimate. Brown takes that notion a step further, suggesting that Mary might likely have been a prostitute or engaged in some form of sexual impropriety. He even includes a chapter where Matthew struggles to write his gospel, before a chance encounter with a young girl inspires him to include Mary’s “lineage” in his text as a sign to clever readers.

With this emphasis on prostitution and sexual liberation, it seems at first as though Mary Wept is intended to be a thematic follow-up to Paying for It. Far from being a personal memoir (though there are aspects of that) Paying is instead turned out to be a libertarian polemic in which Brown makes the case for not only decriminalizing but deregulating prostitution.

Regardless of your feelings on the topic, there were many problems with that book, one being his refusal (out of consideration) to draw the faces of the prostitutes he visited, inadvertently dehumanizing them. The other was the extensive series of notes included in the back of the book, in which Brown made huge leaps of logic that led to him imagining a perfect world where everyone has given up on romantic love and is having sex for money with no consequences (one critic dubbed this utopia “whore Epcot”).

So is Mary Wept just Brown doubling down on his previous polemic? Possibly, but then there’s the strange version of Cain and Abel that opens the book. In this rendition, Abel is openly rebellious of God’s law, eating and then raising animals instead of tilling the land. Yet he’s ultimately rewarded by God for his disobedience, while Abel, who obeys his father and God’s laws, is not. How does that figure in with these stories of prostitution?

There are two key chapters that reveal the true theme of Mary Wept. One is the parable of the talents, where three servants are given part of the master’s riches to manage while he’s away. They are then rewarded or punished according to how faithfully they were able to handle his affairs. Extrapolating from an early, Aramaic version of the story, Brown imagines that the one servant who blew the money on whores and other momentary pleasures is the one who is ultimately rewarded by the master for his actions; the one who invested the money is merely “a disappointment.”

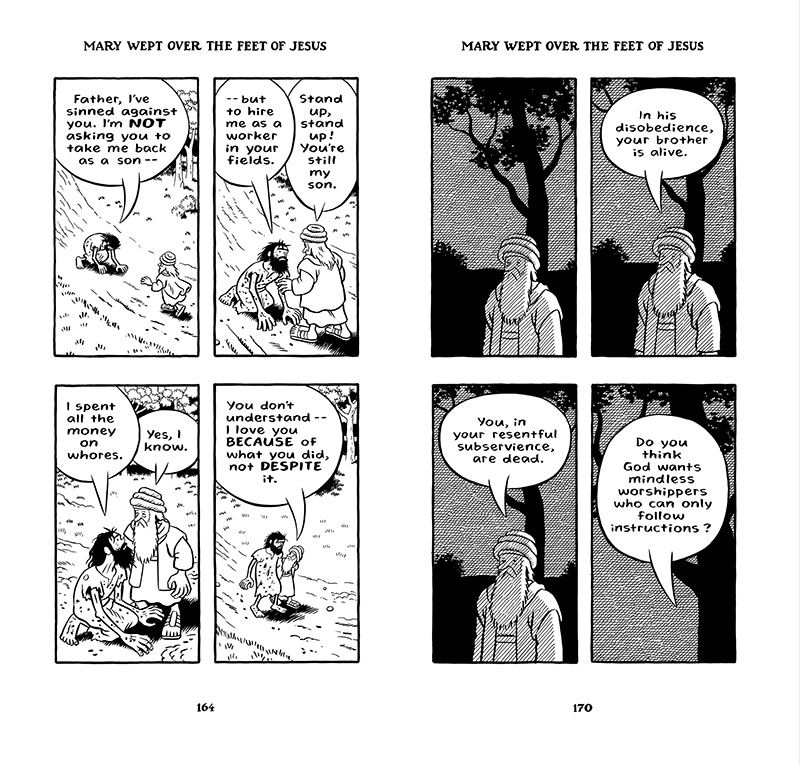

He goes even further afield with the more familiar story of the prodigal son. In his version, the wayward son is celebrated and honored by the father for having the tenacity to cavort with whores and gamblers, not for the courage to come back repentant. Brown’s key argument then, is that open defiance (especially if it involves paying for sex) is far more preferable to unthinking obedience in the eyes of the Lord. As the father in this story chides his other, more respectable son,“Do you think God wants mindless worshippers who can only follow instructions?”

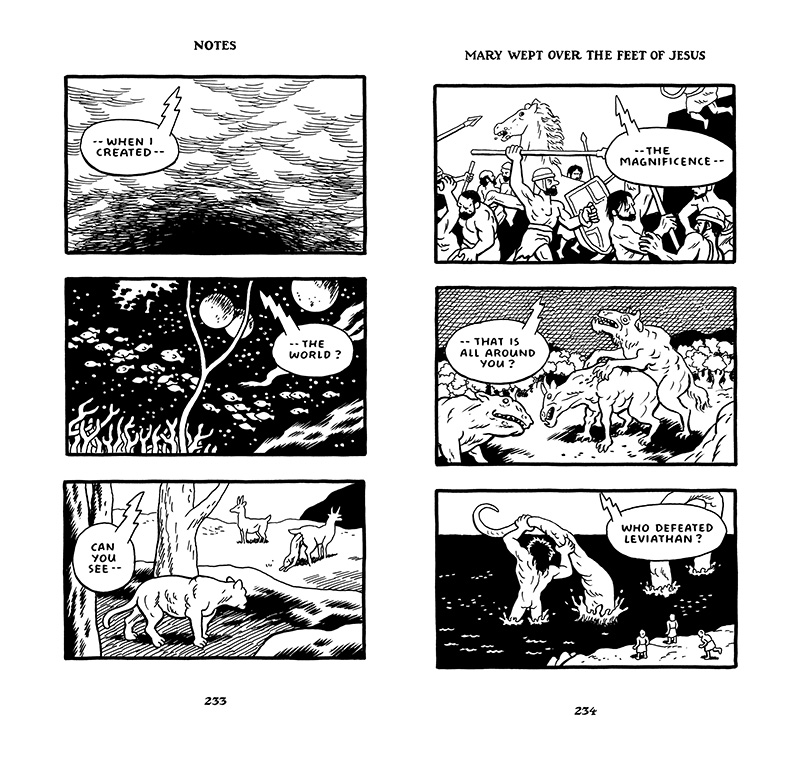

Lest you fail to appreciate this point, Brown has helpfully included an extensive set of notes that take up a third or more of the book (about 100 pages), where he cites sources, notes differences, and explains himself over and over and over again. There is an afterword, acknowledgments, notes, and then notes on the notes. Some of this is fascinating. Some of it is persuasive. Some of it just raises eyebrows (his interpretation of the prodigal son story can be summed up as “I got a feeling this is what they REALLY meant. Trust me”). And sandwiched in the midst of all that is Brown’s adaptation of the Book of Job, one of the most stellar comics in the entire book and all the more confounding for its ancillary inclusion.

Mary Wept is drawn in what can only be described as perhaps the most nonplussed style imaginable. Highly influenced by Little Orphan Annie creator Harold Gray, Brown has fun with cartoonish caricatures (noses are a speciality of his) but his characters rarely display any kind of emotion. and speak in the most declarative of sentences (“If my husband won’t satisfy my needs, I have a right to have them satisfied by someone else,” Bathsheba says at one point, throwing stones at the patriarchy). Again, this is all no doubt to prevent the reader from somehow misinterpreting Brown’s argument.

All of which is not to say that there isn’t some stellar cartooning going on here. Brown imagines God as a naked giant, always seen from the back, towering over lesser mortals. When Mary is visited by the angel Gabriel, we only see Gabriel’s feet, dangling in mid-air. When God reminds Job who created the heavens and the Earth, we see panels of volcanos erupting, armies battling, and frightening monsters mating. Even in the more placid scenes, his tight control over his line and unerring sense of composition is exemplary.

As a work of art, Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus captivates. As a scholarly argument, however, it fails at least in part to persuade, thanks largely due to the notes, where Brown’s extended series of hair splits and hoop jumps often feels like he’s trying to shove a square peg into a round hole (sexual allusion not intended). Brown (who calls himself a Christian in the notes) is on to something when he questions whether adherence to doctrine equates with a closeness to God, but ultimately, Brown is better at raising questions than at explaining his reasoning.

Still, Chester Brown remains one of the most idiosyncratic and striking voices in comics. Few cartoonists would be willing to tackle a project of this nature, while in the process laying bare his experiences and personal philosophies in the same manner. If Mary Wept falters in coalescing his grand theory, it’s still wonderful to watch him pull all the disparate parts together. •

All images courtesy of Chester Brown and Drawn & Quarterly.