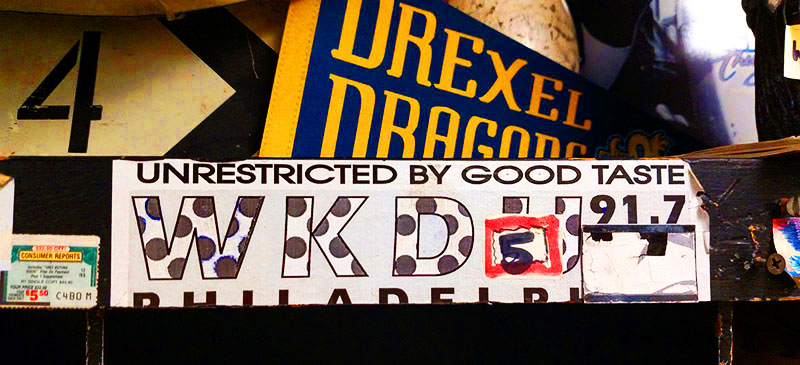

I stumbled out of the wormhole that was the first few weeks of freshman year and landed at a new member meeting for WKDU, Drexel’s student-run college radio station. A few dozen freshmen, overconfident in their music taste, gathered in an appropriately dingy meeting room. The guy directing the meeting had a pink sticker on his laptop that bore a faux Nike swoosh, underscored by the word “cunt.”

The (impossibly cool) DJs walked us through the basics: what they do, what the training process is like, what it means to be part of WKDU, and their longstanding policy of no top 40 music — from ever, forever. A group in the back sporting t-shirts of some such bands wrinkled their noses and pulled out their iPhones. I leaned in.

Elvis Costello, “Radio, Radio”

Audio PlayerWKDU has been around since the ‘50s or the ‘70s, depending on whom you ask and what you consider to be a radio station. Like so many other college radio stations, it is a launch pad for local bands and has taught a generation or two what life is like on the FM dial. Many college radio stations have become part of public radio entities or no longer let students choose the music they play, but WKDU remains un-anaesthetized: student-run and free-format. Its only stakeholders are the DJs and the listeners, and most DJs will tell you that they don’t give a shit who listens or what anyone thinks of their musical choices. This results in programming which is wildly inconsistent and wildly creative — and sometimes offensive.

The rise of digital music and corporate radio consolidation has caused most stations to restructure their programming, taking control from the DJs and giving it to more established entities, like the university or public radio. At WKDU, neither the University nor the station tell DJs what to play. If they feel like it, the DJs take listener requests. WKDU strives for the offbeat aesthetic — unrefined, gritty, and generally pissed at the establishment — as it has from birth.

I stuck around the meeting for long enough to follow Cunt Sticker Guy into the basement of the building for a tour of the station. Past the duck hunter gun-turned-doorbell lay a zone seemingly beyond the control of Drexel’s straight-laced, starched, white-collar authority. Every door was covered in band and bumper stickers and scrawled with profanity. Fading concert flyers lined the walls. The ceiling, covered in two warring factions of hot-glued army men, looked on the verge of collapsing (it hasn’t yet). My guide gestured towards the record library with little fanfare. I leaned around the doorway to find a floor-to-ceiling shelf of records — you know, vinyl ones. And another behind it. And another. Walking down the narrow aisles, I brushed shoulders with half a century of musical history and breathed in the musk of decomposing cardboard: It was love at first sight, if such a thing ever existed.

I was fresh out of a small-town high school where I spent many afternoons sitting in my boyfriend’s basement listening to old punk and rock records on the turntable he rescued from the negligence of the school’s librarian. We felt so untouchably cool in the way that only rural kids who have reclaimed the culture of their parents can be.

Walking into the library at WKDU was like seeing the earth from space. There just seemed to be so much. How could I ever know it all?

So I joined the radio station.

Iron and Wine, “Boy with a Coin”

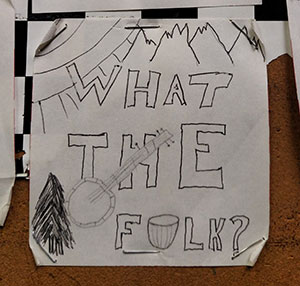

Audio PlayerMy first show was called What the Folk?! — punctuation not optional, grudging laughter appreciated. Like me, the sound of folk music seemed deliciously out-of-place in concrete-and-steel Philadelphia, and I had a passing interest in the genre. How better to get to know folk than to curate two hours of it every week?

Creating each week’s playlist was a scramble which culminated in a crisis of confidence. I won’t have enough music; my taste is terrible; I know nothing; no one will listen anyway. I readied myself like a doomsday prepper for those shows, picking every song carefully, ordering them meticulously, and listening and re-listening until I had no choice but to go on air. I played a lot of mediocre music and the gaps between songs ran too long. I was terrified and terrible, but I was exhilarated enough to know I would stick with it long enough to hit my groove. This was the first time I was at the helm of my own musical education, untethered to the tastes of my parents, friends, or significant others.

Creating each week’s playlist was a scramble which culminated in a crisis of confidence. I won’t have enough music; my taste is terrible; I know nothing; no one will listen anyway. I readied myself like a doomsday prepper for those shows, picking every song carefully, ordering them meticulously, and listening and re-listening until I had no choice but to go on air. I played a lot of mediocre music and the gaps between songs ran too long. I was terrified and terrible, but I was exhilarated enough to know I would stick with it long enough to hit my groove. This was the first time I was at the helm of my own musical education, untethered to the tastes of my parents, friends, or significant others.

I became a better DJ – slowly. I figured out what I liked and what worked. I made friends at the station: we exchanged mixtapes and I sat in on their shows. I cultivated a radio persona that didn’t sound panicked. I developed muscle memory for working the mixing board. People I didn’t know started listening to my shows regularly. When the most devoted listener of WKDU, a caller known to every DJ simply as Jah Bless, called in to my show and referred to me as “empress,” I knew I had arrived.

I hosted What the Folk?! for more than a year. Tapping my toes to banjo beats two hours a week, I earned my place at the station.

Mike Pays Heat, “Breaking Pencils”

Audio Player

Weekend nights, Drexel’s music scene goes underground. The basements of Philly rowhomes open their doors to floods of underage kids wearing too much flannel and seeking beer and ear-blasting, oft-mediocre (but sometimes life-changing) music.

Let me take you to a basement show.

Hand the guy at the door five bucks. He’ll draw a crooked x on your hand in sharpie. The house smells like cigarettes and old beer. People lounge on broken furniture in the living room because they can’t fit any more people in the basement, but it doesn’t matter — we can feel the bass radiating up through the floor. And we’ve all seen this band before anyway. We know all the lyrics.

Downstairs, anyone taller than six feet is likely to hit their head on the beams holding up the first floor. We crowd into this cramped, sweaty, poorly lit basement for the privilege of losing our hearing, one aspiring indie band song about underage drinking at a time. The ambiance of old record sleeves, tapestries, and strands of half-broken lights seems both casual and meticulously crafted. Despite the low headroom, people slam dance, knocking over the band’s mic stands. The music is an excuse — a connection that gets us to the same place as some people we know and some people we might want to know better.

We are just a bunch of awkward kids standing in a basement, screaming angst-ridden lyrics at each other. But this is how we’ll grow up.

I still go to basement shows sometimes to feel the blur and connection, the darkness and closeness of a Philadelphia basement. Mike Pays Heat — a band made up of friends, a few DJs at WKDU — played at least a dozen basement shows I went to. We screamed the last verse of this song at each other. When we made it to the front, we held hands to keep the slam-dancing attendees from knocking over the lead singer. We stood together on the front line of college music.

Dan Deacon, “When I Was Done Dying”

Audio PlayerMy best friends from WKDU took me to my first Dan Deacon concert. I barely knew his music, but they told me to come anyway. In the church basement, we sat crisscross-applesauce on the floor while the best opener I’ve ever seen — a comedian — gave a PowerPoint presentation about his cult, which is based on the philosophy of Dr. Bronner’s all-one soap (Intrigued?). By the time Dan came on stage, the room hummed with happy, zany energy.

Dan’s music is enough — it sweeps you along in waves with it, makes you want to sway and dance. But Dan himself is the show. By the end of the first song, I was enchanted. Stage presence doesn’t cover it — I wanted to be his friend. Midway through the show (I don’t remember if it was pre- or post-dance contest), he told everyone to take a breath. He told us to put our hands on the heads of the people in front of us — I’m sweaty as hell so this is weird, but okay, I guess — and to feel each other’s energy.

The next time I saw him live, at a crazy music festival in Washington, D.C., when he told us to hold hands with our fellow concert-goers and close our eyes, I was ready to embrace the weird. “Picture the face of the person you love most in the world.” And then he told us to picture the person we missed most in the world. And then the face of the most recent person of color shot by a figure of authority in the United States.

“That person — they are the person that someone loves and misses most in the world.”

Half the crowd — including me — teared up. A few started to cry. Not 15 seconds earlier, we had been caught up in the happy slamming of a music festival. The adrenaline and realization of other people’s pain hit us all at the same time. The guy next to me squeezed my hand, and I passed it along. There was a collective breath. And the music carried us along again.

Jonathan Richman & the Modern Lovers, “Roadrunner”

Audio PlayerEventually, I got sick of folk music. I had gone as deep into the genre as I cared to, and, while I still loved listening to singer-songwriters with a banjos, I had started to dread making each week’s playlist. To get out of the folk funk, I renamed my show Strawberry Shrapnel and filled in the genre boxes with adjectives like “spiky” and “sparkly.” Each week, I tried out new things, and I played whatever sounded good to me at the time.

A few months into my new genre exploration, in the midst of assembling my weekly playlist, I came across a band called the Modern Lovers. I derailed my playlisting for an hour to listen to half of their discography: leaned back in my chair, eyes closed. I looked up the band, and I texted my friend and fellow DJ.

“I think I found my genre. It’s protopunk.”

He was my first friend at WKDU. Probably a good part of the reason I’d stuck around through the whole thing.

He was my first friend at WKDU. Probably a good part of the reason I’d stuck around through the whole thing.

“Sounds about right,” he said.

I was staring at the protopunk Wikipedia page (hint: if you want an express musical education, get a Spotify account and get good at using Wikipedia). The genre is the loosely defined missing link between the Beach Boys and the Sex Pistols: minimalist, frenetic, and raw. The noise — the grit — and the attitude of the genre scratched an itch I hadn’t known needed scratching. It was nostalgic for the punk revolution, and I was too. (Though I didn’t live through it, I wished I could.) I wanted to understand what caused people to break into rock and then break into punk — probably they just needed to break something.

And me — I needed a break out of a stuck state of mind. Protopunk was just the right soundtrack.

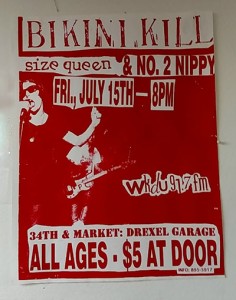

Bikini Kill, “Rebel Girl”

Audio PlayerFor the duration of the summer of 2015, I was the only female undergraduate DJ at WKDU. There had always been a gender imbalance, but, like everyone else, I had attributed it to a combination of Drexel’s overall male prevalence and chance. All my DJ friends were dudes, which I didn’t mind most of the time.

There were a few times I’d felt out-of-place — but hey, who doesn’t sometimes? I had walked in on a bunch of DJs “rating” the attractiveness of a female new member (she didn’t finish her DJ training). I heard about a guy who hooked up with a few girls at the station and had bragged to his friends that he had “conquered” WKDU. Sometimes I’d offer to help with something technical — made it clear I was eager to learn — and got brushed off. These were “isolated” incidents, ones that had happened after I was already a DJ, so I ignored them. This was the place I loved and the thing I loved to do: Subtle sexism is the going rate for being part of a movement, right?

But there was something about realizing I was the only female DJ that took the wind out of me. There hadn’t been many women at the station before, but the ones who stuck around were tough and smart, hardened by an education in girl punk. I looked up to them. Then suddenly the last few graduated, and while some kept their shows, they weren’t hanging around the station like they had been before.

But there was something about realizing I was the only female DJ that took the wind out of me. There hadn’t been many women at the station before, but the ones who stuck around were tough and smart, hardened by an education in girl punk. I looked up to them. Then suddenly the last few graduated, and while some kept their shows, they weren’t hanging around the station like they had been before.

This was not a fraternity; I did not sign up for this. I was on the exec board — the only woman there too — and that meant maybe I could do something about it. I gathered my allies, but when we pointed out just how skewed things had become, we heard more than just a few objections. Most of the guys attributed it to chance and to Drexel’s climate, too. But it was something that went all the way back to my first WKDU meeting with the guy with the sticker on his laptop. I know now that he’s a great guy, but that had to make an impression on other young women who wanted to be DJs. I saw girls who started training, got hit on by older male DJs, got creeped out or got their hearts broken, and left. Unlike the people who were already on the inside, they were not blind to the gender disparity, and membership to the station wasn’t worth the price of entry.

David Bowie, “Rebel Rebel”

Audio PlayerFor three years, college radio has got what I need: the perfect combination of rebellion and community. It’s creative and destructive, challenging and freeing, complicated and so simple. And not just for me — WKDU has been a refuge and a playground for generations of DJs. Some of those DJs have stuck around for decades. Listening to their stories, I realize that so much — and nothing — has changed.

When you put someone on air, you give them a lot of power. If I’ve learned anything these past years, it’s that most people will rise to the occasion. The spirit of WKDU — the community, the music, the love, the identity, the rebellion — is infectious.

This year, we welcomed over a dozen new DJs into the chaos. Some were women. It is not enough — the station is still primarily white and male — but it’s a start. Giving women a voice in radio, even when a “good voice for radio” is assumed to be a deep male voice, gives them power.

Some people paint a dim picture of the future of college radio. WKDU is one of the last of its kind, so maybe they’re right. But until it goes off air for the last time, WKDU will be the haven of the vinyl-chasing, music-loving, angst-ridden college DJ. •

Art and photographs courtesy of the author.