Modernism first began to die in the 1960s. There was serious talk. People were getting fed up. A new sensibility was beginning to emerge, if only at the margins. That discussion heated up in the `70s and it was super-trend, can’t-have-a-conference-without-it material by the `80s. As Jean-François Lyotard wrote in his epochal The Postmodern Condition (1979), “Our working hypothesis is that the status of knowledge is altered as societies enter what is known as the postindustrial age and cultures enter what is known as the postmodern age.”

Alteration was all the rage. We were altering. This was either the ground for a new optimism, wild and exuberant in its embrace of the new terrain, or deeply pessimistic in the face of the collapse of every possibility for genuine critique. Someone like Jean Baudrillard could proclaim, “Modernity has never happened. There has never really been any modernity, never any real progress, never any assured liberation. The linear tension of modernity and progress has been broken, the thread of history has become entangled.” And someone like Terry Eagleton could write, ”The postmodern prejudice against norms, unities and consensuses is a politically catastrophic one.”

But the excitement of alteration ran into something of a funk. Neither did there seem to be a liberation of human possibility after the demise of the last meta-narrative nor a complete obliteration of human initiative in the face of the new capitalist hegemony. In many ways, it seemed that in the face of all the rhetoric and transformative talk, “keepin’ on” was somehow managing to keep on. And so the `90s passed away, as did the fin de siecle.

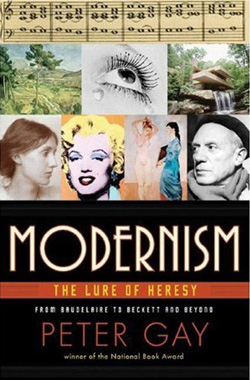

These days, we’re weary of being weary. But that gets us nowhere. Then, into the midst of all the funk and gloom, comes one of the most boring books of our time. And it is as deeply satisfying a dull torpor as we’ve been gifted in recent memory. The book is Peter Gay’s Modernism. It is something akin to a high school textbook, with categories like “Prose and Poetry,” “Music and Dance,” “Architecture and Design,” and the like. Gay, in explaining the difficulties presented to anyone trying to write a history of Modernism, says:

Not surprisingly, then, cultural historians intimidated by the chaotic, steadily evolving panorama they are trying in retrospect to reduce to order have sought refuge in a prudential plural: “modernisms.” This compliment to the turbulence that pervades the modern marketplace for art, literature, and the rest shows due respect for an imaginative individuality that has for almost two centuries ignited spirited debate over taste, its expressiveness, morality, economics, and politics, and over their psychological or social origins and implications.

The turbulence, Gay suggests in 510 pages, is very much over. And he has the prose to prove it. Modernism is dead. We all knew this, of course, but we still didn’t necessarily believe it. We needed to go to the funeral. We wanted to see the body. Now we have. Peter Gay is our undertaker. We needed someone to do the job of writing the final obituary for Modernism and it was such an immensely tiresome task that we left it off for more than 20 years. We were bad. Peter Gay, a good man, has finally stepped to the fore. He has written one of the least engaging books of our time. And this, I submit, is the perfect antidote to our lingering discontent. Peter Gay is a hero. He writes sentences like the following: “This climate, the essential prerequisite for the modernist revolution, was an atmosphere in which society could accept, however reluctantly, drastic departures from settled artistic habits, entertain unfashionable opinions about beauty, and tolerate conflicts among styles.” The is like an answer to a question in a Western Civilization 101 course; namely, “What is the essential prerequisite for the modernist revolution?”

But it all makes me very happy. The fact that Mr. Gay could write his soporific tale of the last great movement in culture means that the discussion is over. It is done. Done. And that means that we are truly ready, ready in a mature sort of way, for a new discussion about where we really are and about the questions we’re really facing. Let’s put the first round of Postmodernism to bed along with all the rearguard defenses of Modernism that have lingered in the public discourse for a decade or three too long. Let’s start afresh. Let us just say that we don’t know exactly where we’re headed but we know that the territory requires some serious flexibility on everyone’s part.

We can do this, I think, in a new and honest way because of the work of Mr. Peter Gay. It is a book that guarantees that Modernism will cease to be interesting for at least a generation or so. It’s the eulogy that everyone else was afraid to write. Rest in peace, Modernism. • 19 December 2007