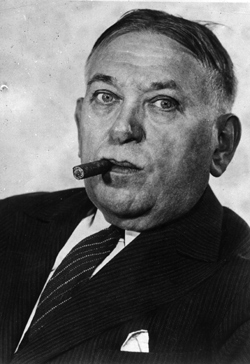

H.L. Mencken was a bastard. He had a core meanness that showed itself in his writing and in his personal life. Without that meanness, though, his writing might never have gotten so startlingly good. Lots of people need lots of things to do what they do. Mencken simply needed to be hard.

In the early part of the 20th century, America needed Mencken. We needed him to wash away some of the Emersonian/Whitmanian enthusiasm that had started to clog up the collective joint. Not that Emerson and Whitman didn’t have their place. As Mencken himself notes in his essay “The National Letters,” it took Emerson and then Whitman, among others, to stand up and defend the possibility of an American Mind and an American Voice. They did so with boldness and with prose falling over itself in its excitement about itself. Sometimes with Whitman it seems that we’re but one or two orgasms away from the final utopia of ecstatic democracy. This newfound confidence, speaking out, proclaims that America has finally figured out what it is. An American literature of the late 19th century was coming out of the Wilderness with something to say.

Mencken wasn’t so sure. Surveying the landscape in 1920 and musing about what had been accomplished in the wake of all this exuberance, he had this to say about our literature: “Viewed largely, its salient character appears as a sort of timorous flaccidity, an amiable hollowness.” Mencken then proceeds over many pages to tear the national character a new one. He was tired of the failures, tired of all the empty praise. His corrective to the ongoing disaster of American literature had a name: Theodore Dreiser.

Writing about Dreiser brings something grand out of Mencken; it drives him to say something distinct about what we ought to be up to and why. His essay on Dreiser from 1916 is a delight to read. He revels in Dreiser’s writing while still admitting that Dreiser may be the sloppiest writer in living memory. Everyone who’s ever read Dreiser has wondered where those chapters and chapters of endless description are going exactly. Everyone has wondered at the syntax and verbiage so tortured — it wouldn’t be surprising to find out that Dreiser sent the pages direct from the typewriter to the printer. Of Dreiser’s The Genius, Mencken says, “There are passages in it so clumsy, so inept, so irritating that they seem almost unbelievable; nothing worse is to be found in the newspapers.”

But within the mess, Mencken divines a singular and pitiless voice that’s hard not to associate with Mencken’s own. It’s a vision of the human struggle that is “gratuitous and purposeless,” a voyage that is undertaken “without chart, compass, sun or stars.” Mencken saw in Dreiser a companion in this struggle, the project of staring into the void for as long as possible without flinching. He made a hero of Theodore Dreiser because Dreiser was writing about a different American truth, about hapless people muddling their way through just like in any other country. At the end of his essay on Dreiser, Mencken manages to pull out of himself what I take to be his finest single thought, as beautifully expressed as it ever has been, by anyone. Summing Dreiser up one last time, Mencken writes: “His moving impulse is no flabby yearning to teach, to expound, to make simple; it is that ‘obscure inner necessity’ of which Conrad tells us, the irrepressible creative passion of a genuine artist, standing spell-bound before the impenetrable enigma that is life, enamored by the strange beauty that plays over its sordidness, challenged to a wondering and half-terrified sort of representation of what passes understanding.”

Ironically, with that one sentence, Mencken redeemed American literature (at least for a minute or two) and realized something of the promise that Emerson and Whitman had gestured to with such profound, irrational hope. But with Mencken, there is no glorious tale to tell, just the desire that someone express the crappy truth as the only glory we’re likely to grasp. And it was, in a sense, his meanness that allowed him to do it. It was also his willingness to look to Europe again in order to see how his countrymen measured up after all the grand claims. To Mencken, it didn’t look so pretty. Europe, to him, was still the measure and he was blunt in expressing that fact. The Teutonic mind and spirit struck him as vastly superior and he honored himself in refusing to bash Germany in WWI and then dishonored himself in waiting far too long to raise a strong voice against National Socialism heading into WWII. His fetish for what he saw as the aristocracy of intellect over there and his contempt for the democratic herd over here were part and parcel of his project. It was the cost, as it were, of his reaction to what he saw as the overreaching optimism of the literary generations that preceded him.

America had grown up in the decades between Emerson and The Smart Set. In growing up, it gave birth to a brilliant little beast named H.L. Mencken who had the stomach to stare into the odd abyss, to look hard at the “strange beauty that plays over its sordidness.” In rejecting Emerson’s and Whitman’s hope he had to leave behind the vestiges of American Exceptionalism that still linger in Emerson’s rhapsodizing and in Whitman’s singing. He had to show us in our dumbness, engaged in the same fruitless struggle that lays low every beast in time. Funnily, and in spite of all his maddening missteps of judgment, Mencken — in being such a relentless bastard year after year — gave the American voice back a little of its humanity. For that reason alone his birthday, last week, ought to mean something now and for a long time to come. • 19 September 2007