Although I consider myself an atheist, my lack of faith always wavers around the High Holy Days. These are the sacred days of the Jewish calendar that extend from Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, to Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. During this period of about a week, as the joyous holiday leads into the somber one (“on Rosh Hashana it is written, on Yom Kippur it is sealed”), I am always visited by a memories of my childhood rabbi, an iconic figure, who embodies, for me, religion at its most beautifully contradictory.

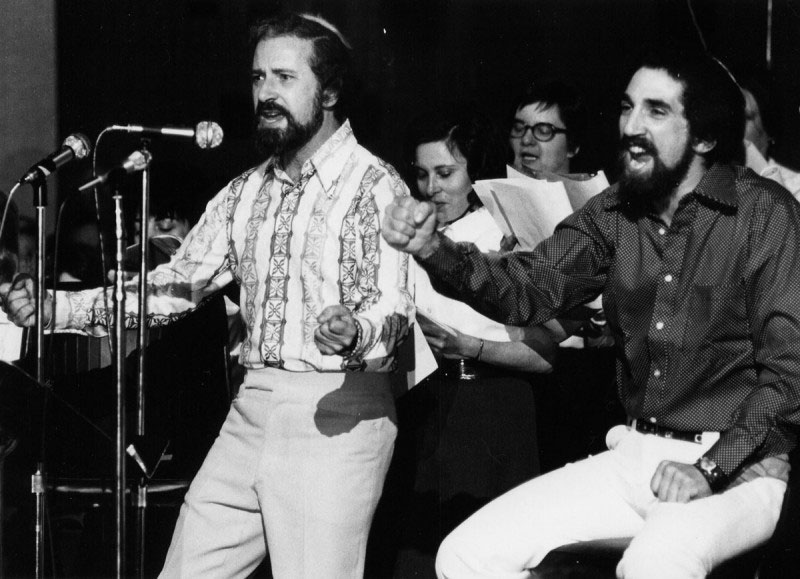

Z. David Levy — do any of my readers know the name? He was a minor celebrity during a span of about 15 years in the late ’60s and ’70s in northern New Jersey. The first initial was always used — an emblem of his originality, with the added advantage of allowing me to track him down after he had retired to Florida.

TSS on The High Holidays

Rabbi Levy was the sort of figure who inspires mythic attachments when encountered at an impressionable age. I met him first when I was in elementary school. My parents had joined the newly organized Reform Temple in Morristown, New Jersey, then housed in a converted office building on the outskirts of town. Levy had been hired by this ragtag congregation as rabbi and cantor both, though he had never occupied either role before. He had been working as a jazz drummer and singer in Greenwich Village. Why he left the one career for the other always remained mysterious. Was it a sudden welling of religious fervor (his father, against whom he had originally rebelled, had been a rabbi), or was he escaping the Mob or a jealous mistress? Any of these — or all — might have been the case. If you had known him, you would understand. What we did learn soon after his arrival was that his wife was not happy about his change in career. She left him soon after, announcing that she had married a jazz drummer, not a Jewish prophet.

This is precisely what he set himself up to be. He loved to expound and proselytize — not so much on religion (at least not in the early days) but on social justice, which, as I approached adolescence, jibed with my idealistic leanings. This was the era of the Civil Rights movement and the Vietnam War protests. Rabbi Levy embraced the spirit of the age without reserve. He marched in Selma, Alabama, worked for fair housing, and read the names of the war dead in front of the municipal building. He forged alliances with black churches in the area, who came to our temple to sing gospel music, his own lyric baritone accompanying.

As the ’60s turned into the ’70s, he grew long sideburns, wore bell bottoms, and acquired a guitar. We now had hootenannies with the Unitarian Fellowship up the street. His sermons took a related turn, with citations from Camus and Sartre. He did not lose his progressive attitudes, but his perspective grew more generalized and philosophical. Eventually, he also became more theological.

In the early years, sprawled in a chair in front of our Sunday School class, he encouraged us to think irreverently. He even admitted that he didn’t know if he believed in God. “Does it matter?” he asked us, as we gazed up at him, full of admiration for such a cool question coming from a rabbi: “Doesn’t Godliness consist in good works — not believing so much as doing?”

Later, however, he grew more ostensibly pious. References to Spinoza, the great skeptic, gave way to citations from more straightforward Jewish sages like Hillel and Maimonides. In one sermon of this period, he went so far as to lecture the congregation for not showing up in greater numbers for Friday night services. The old guard, who had hired the Greenwich Village drummer, were angered. They resented being told to be better congregants (though, personally, I think it was less about Rabbi Levy expecting institutional fealty than about his wanting a larger audience).

But even as he grew more conventional in some respects, he remained rich in rhetoric and imagination. He quoted Buber and Dostoevsky, Dr. King and Gandhi. The allusions tumbled together, though not always accurate, were nonetheless inspiring. “What matters most,” he reminded us, “is our fellow man and how we treat him.”

As the above statement suggests, pronouns were not as carefully weighed then as they are today. Nonetheless, I always knew that Rabbi Levy was referring to women as well as men. As it happened, he loved women. A bit too much. He kissed all of them on the lips after services — even the older ones. For his second wife, he chose a dashing divorcee in the congregation — a fashion plate who sat in the front row during High Holy Days, modeling her new hat and her magenta lipstick. Eventually, she left him too — giving the same reason that his first wife did: He was too much of a rabbi, not enough of a husband. She wanted him home to unclog the drain, discuss the kitchen renovation, and pass along juicy congregation gossip; he wanted to be counseling the distraught and bereaved, giving his long improvisational sermons, and talking philosophy with the Confirmation students.

Even his detractors admitted that his voice alone was worth his increasingly hefty salary — not just his sonorous speaking voice but his brilliant singing voice. In the early years, he relished his ability to move back and forth between rabbi and cantor. Once the congregation grew prosperous and moved into a blond wood edifice on a large, landscaped property, another cantor was hired to perform the perfunctory singing duties. This allowed Rabbi Levy to take the choicest bits for himself or take over when the spirit moved him. It was a wonderful arrangement for a showman. We never knew when he would suddenly step forward and let loose that richly expressive voice — half soaring, half sobbing. We shivered in our seats when he did and, for those moments, were convinced that there was a God and that Rabbi Levy was in direct contact with him.

for those moments, were convinced that there was a God and that Rabbi Levy was in direct contact with him.

I can’t fully express how much I loved him. He was so magnificently and sloppily eloquent, so profoundly alive and flawed, so much the incarnation of a childhood idol. After the second divorce, there were rumors of affairs and indiscretions. He had a daughter from his first marriage with severe mental problems whom he sometimes mentioned in his sermons with a pathos that wrung the heart. One day, after I had left for college, it was announced that he was marrying a third time — to a fellow musician, whose long blond hair we had stared at for years as she played the organ in the balcony above the sanctuary. It was both scandalous and delightful. She wasn’t Jewish! But they had worked together for so long, and her hair was so brightly yellow, absolutely New Testament angelic, much as his now substantial beard was Old Testament patriarch.

Some members of the congregation were huffy, but most shrugged. They knew what Rabbi Levy was like. This marriage was not out of character. And it turned out to be felicitous. She converted to Judaism; he settled down. By then, both my sister and I were living in another city, but we returned home to have him preside over our weddings. At each of the ceremonies, he mixed up our names and our husbands names and forgot what it was we did for a living (I became the poet and artist, she the writer and educator). But of course, we forgave him. He performed the ceremonies with panache and danced wildly at the receptions.

Not long after that, he had a heart attack while blowing the shofar during Yom Kippur. A dozen doctors ran to the front to help out, and, though he recovered, he was not the same. Soon after, he retired, first to Massachusetts, where he and his wife opened a bed and breakfast, and finally, in proper elderly Jewish fashion, to Florida. I tracked him down in these last years of his life. It was a poignant reunion. Once again, he confused me with my sister, but the kisses, the gush of words and ideas enveloped me in a great, comforting embrace. I heard that he had died a few years later.

And so, when I hear the Kol Nidre, that great work of gravitas that marks the beginning of Yom Kippur, sung well (sung as it is on this website, with beauty and fervor, by Dr. Daniel Shidlow below), I am transported back to Rabbi Levy singing it, and bringing me closer to that God in which I do not believe. •