A softly-sung tune signals the beginning of the High Holiday service; the plaintive melody aims to imbue each individual with a feeling that their spiritual presence, rather than the physical surroundings, create the sacred space necessary to pray as a congregation. At this very moment, I am transported to a new dimension, away from the daily and the decanal, into the realm of music at the service of the soul.

Music has been a part of my life since early childhood. I always liked to sing, belonged to choirs, and listened to music, including opera, on the radio or recordings. My operatic career started at age seven, when I accidentally sat on and broke one of the 78 RPM records of the collection “The Great Caruso,” with Mario Lanza singing “Recondita armonia” from Puccini’s Tosca. I became interested in cantorial music during adolescence, being touched by beautiful melodies of Jewish wedding ceremonies delivered by the most notable cantor of Santiago, Chile (where I was born) — a man with a fine voice, superb technique, and great delivery. Later on, I came to admire the great tenor Jan Peerce, a favorite of conductor Arturo Toscanini. The fact that he could deliver operatic and cantorial music with equal intensity and beauty was most intriguing. I wanted to emulate him.

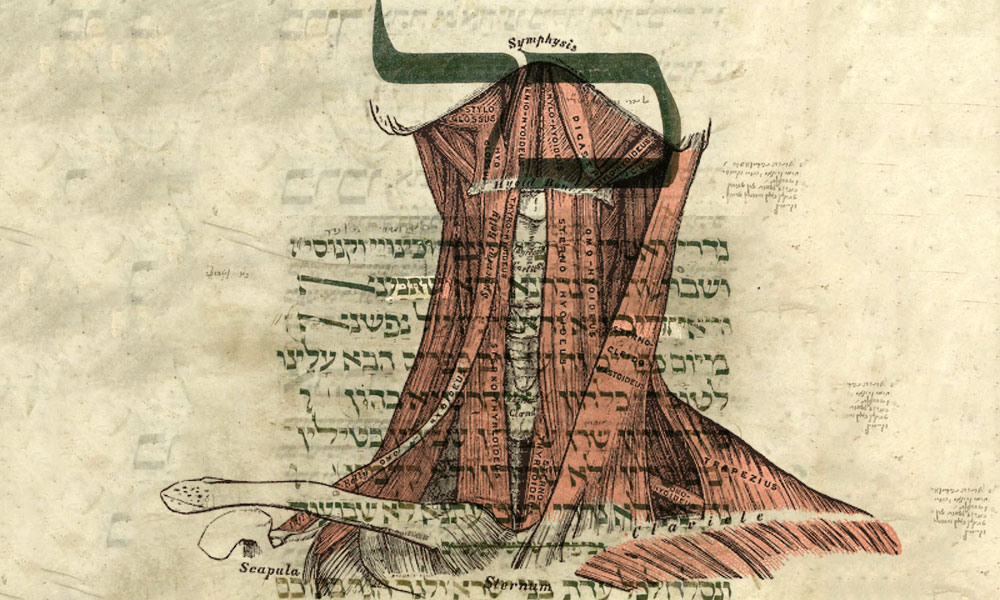

Dr. Schidlow sings the Kol Nidre

I started voice training in my mid-30s and later, studied liturgy (chazzanut) with a cantor whose depth of understanding of the connection between text and melody was unrivaled. On many occasions we would spend the better part of a lesson discussing the musical expression of one sentence of the sacred text. We shared an interest in classical and cantorial music that culminated in a joint recital of operatic and Jewish music on my 50th birthday.

Many people call me “cantor”; however, I have no cantorial degree, no ordination, not even a decent musical education. I am a “cantorial soloist” or a “prayer leader;” on days where my ego needs a boost I enjoy being called “lay cantor.” The correct Hebrew term is Sheliach Tzibur, the representative of the congregation in prayer or “messenger.” Because the Jewish religion is somewhat unstructured, many lay people lead services as an honor during certain holidays. Synagogues that attract “cognoscenti” of religion and liturgy have a veritable team of prayer leaders who can take over a portion of the (usually long) services. The moniker of cantor (or “Chazzan”) should be reserved, however, for individuals employed as clergy who have undergone years of education or apprenticeship and oversee all musical aspects of synagogue life.

In 2011, I acquired another title: Dean of the Drexel University College of Medicine. I soon began to find connections between my two vocations. For example, the word “dean” (or decanal) has its roots in the Latin decanus (a chief of ten) and associated with the concept of an ecclesiastical functionary holding some specific functions and responsibilities. In the Jewish tradition, to conduct services a minimum of ten men are needed (most non-orthodox synagogues will include women in the count). And the similarities do not end there.

The role of the prayer leader is to prompt the congregation to find the meaning and spirit of prayer by means of inspirational delivery of melody and sacred text, and promotion of congregational singing. Music is the vehicle to connect those present with the purpose and the meaning of the moment, whether a holiday or a life cycle event. On a different plane, I believe that deans are called to give direction, inspire and steward members of a faculty to coalesce around common goals and aspirations. Communication, a strong sense of direction and personal commitment to a higher aim, a sense of privilege to be called to serve, and a pastoral proclivity further invoke similarities.

A Cantor’s Vocation

The axiom that one cannot please everybody, or in trying to do so, one pleases no one, is ever-present in both realms. The comments at the repast after service or at social occasions (a favorite time for Jews to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of clergy — and their spouses, if they exist — and to pass judgment) range from exalted views about voice and delivery, to critiques of same, to disappointment with choice of musical selections (too many new tunes is a customary one) or of behavior at public or private functions (aloof or engaging). Favorite corridor comments about the dean include his communication style and accessibility (excellent or terrible), use of humor (enjoyable or flippant), decision-making process (precipitous or too slow), people management skills (fair or arbitrary), or thought processes (independent or unduly influenced by a manipulative team).

TSS on The High Holidays

Any individual who takes singing as a serious endeavor has an exacerbated response to criticism — especially when coming from within — and experiences more than occasional insecurity. Every sung note is the product of a fine balance of a constellation of physical, mental, and environmental factors aligned against a pursuit of perfection. A less than perfect sound generates the same disappointment experienced by an athlete who does not reach his or her expected height, length, or speed. The personality profile of a physician executive generates very high performance standards. Thus, I am my worst critic, whether of my singing or my actions while discharging my decanal duties. A sense of failure to meet this self-imposed measure of excellence generates disappointment and a sense of incompleteness. The only salutary aspect of these feelings is that they curb any attempt to cloak oneself in self-importance and inspire continuous learning, preparation, and dedication. The synagogue pulpit and the conference room share the emotional characteristics of spaces populated by humans. Ongoing inspiration and rededication make retreating to a personal space from time to time all the more important.

On the Kol Nidre

Perhaps the closest the two vocations come together in the non-religious world is the commencement ceremony. The shared emotions, the majestic setting, the invocation and benediction, the commonality of sentiment achieved during those 90 or so minutes as students cross the stage and are hooded by their mentors and teachers, create a veritable sacred space where the divine and the earthly come together.

Internalization of quality, selflessness, and balance in the service of people makes us discover the ultimate ingredient central to both endeavors: connectivity. The rewards that emerge from navigating these two apparently dissimilar but ultimately concordant fields is the fulfilled desire to inspire, to educate, and to achieve a higher plane as human beings. •