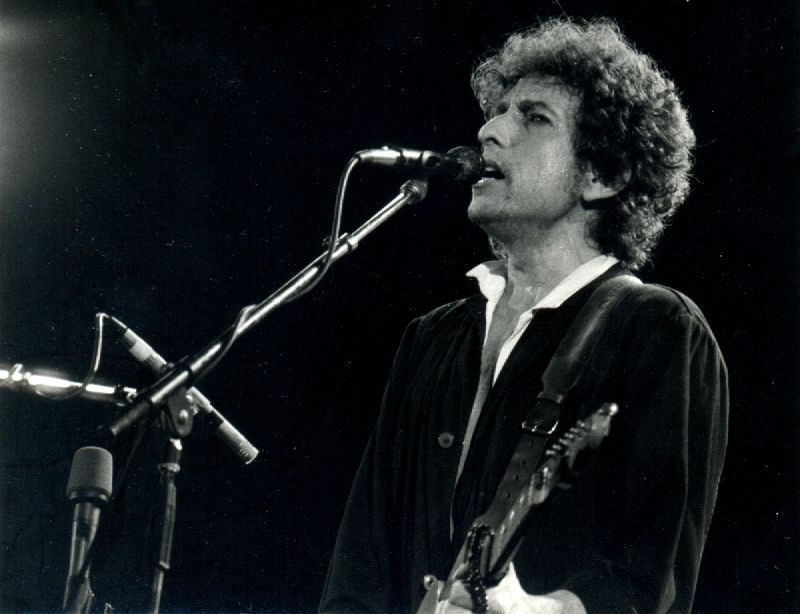

For the first time ever, the jury has given the Nobel Prize in literature to a writer who cannot be appreciated by the deaf. In their citation, the jury lauded Bob Dylan’s “new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” But can song lyrics be rightly esteemed on the page, or do they need a tune and a voice?

Dylan’s lyrics — absent the memory of the chords that fed them life — read like dead fish. But they swim in sounds like nothing else. I remember they do, but deaf, I can’t hear them now. And just as color cannot be helpfully explained to a blind museum patron, so the lilt of a voice cannot be helpfully explained to one who’s deaf. The Nobel Prize in literature has gone to someone I’m no longer able to “read.”

I wasn’t born deaf — I went deaf in my 30s. Before then, I loved Bob Dylan, but I never loved him in the way I love books. This became all the more clear to me when I lost the ability to hear music as I used to and tried to substitute books for what I’d lost.

When I read, I’m taken outside of myself. Reading shows us things we don’t know, whereas pop music finds sounds for the feelings already inside us. When we read, we visit corners of the world we’ll never see, including the psyches of others. When we listen to the songs we love, we retreat inside ourselves.

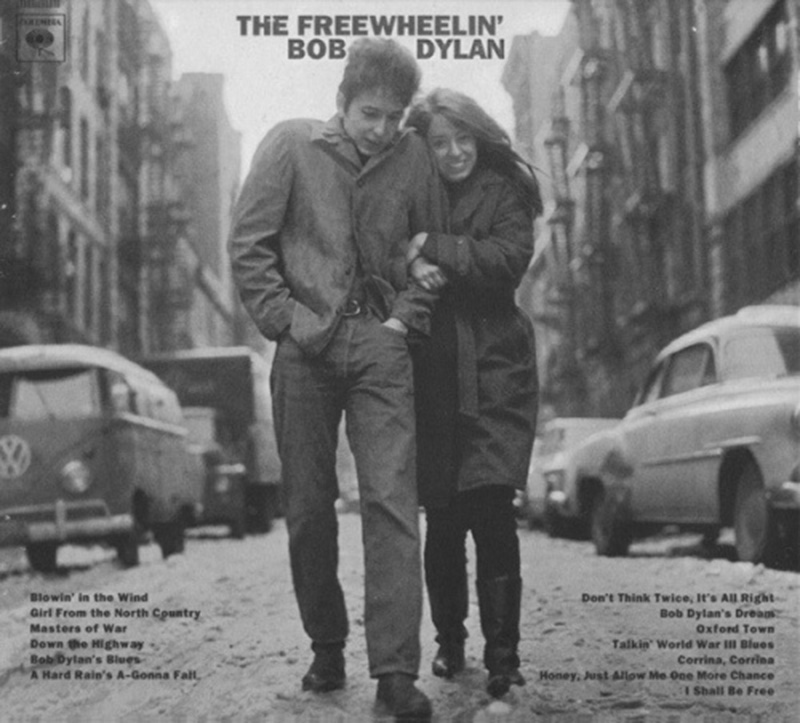

I didn’t discover Dylan in the 1960s, in the very heaven of a world burgeoning with revolution. But his music had much the same effect on me when, late in the summer of ’98, a good friend came by my place with a copy of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan in his hand. “I know, I know,” he said. “But just listen.”

Dylan, until then, was a whiny voice on TV sometimes, a punchline, one half-decent bar-rock album in Time out of Mind, and a lot of bad ’80s music.

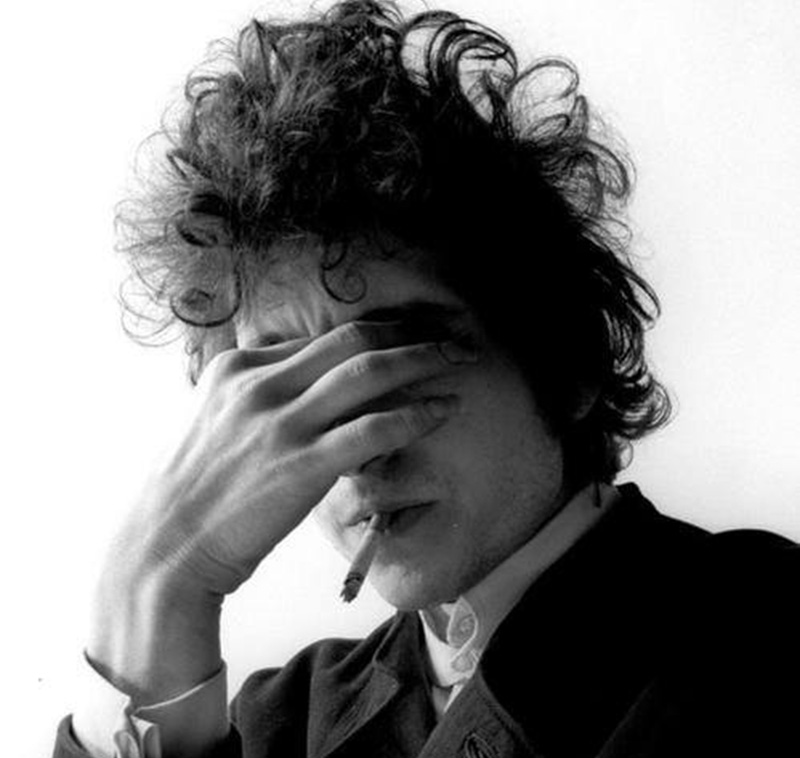

My friend set the CD going on “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.” The first few handpicking licks — base and rhythm on the same guitar — opened my eyes. Dylan was clear when he needed to be and he slurred when he needed to slur. There wasn’t any question of its being the highest kind of art — it clearly was — but it also felt dashed-off, on-my-way-out-the-door; it had a sprezzatura carelessness that made it feel authentic, lived-in, and that enabled me to put on its clothes and wear them as my own. I lived inside the sound.

The final verse of “Don’t Think Twice,” the one where the nonchalant lover leaves his ex, reads, in the liner notes:

I ain’t sayin’ you treated me unkind,

You coulda done better but I don’t mind;

You just kind of wasted my precious time,

So don’t think twice, it’s alright.

New poetic expressions within the great American song tradition. Note the careful wording. “Expressions” is crucial here because if you try to read the verse above as poetry for the page alone, it doesn’t work. Forget issues of appropriation (all rock music by white people tarries with the stuff) and forget the affectation of his listeners, which accepts bad syntax as more authentic than the well-articulated kind. Just note that nothing above distinguishes itself as particularly good reading as such. Minus the background music, minus Dylan’s delivery, “Don’t Think Twice” isn’t worth looking at once.

But performance is everything. Dylan’s voice singing “unkind” at the end of the first line is sweet, almost boyish. But the “I don’t mind” takes it elsewhere — it’s bitter, disingenuous. It’s how you pretend to end an argument without really ending it. By the time we get to “precious time” the voice is smug, too proud of itself. It’s the voice of a huckster, a game show host, selling something in bad faith when everyone’s in on it. And that final “It’s alright” is cold, the door clicked shut. And yet behind the coldness reappears vulnerability. He’s been hurt, and that’s why he’s cold. And so returns our righteousness, our pure emotion, more credible for the shades of expression that have come before it.

The next song my friend played me that evening was “Tomorrow Is a Long Time,” the acoustic version from 1963, the live Town Hall recording. That direct voice and that guitar, so simple and so clear, made me feel, as V. S. Naipaul said about Joan Baez, as though I could hear “the deepest part of myself awakening.” I said aloud to my friend, “You’re kidding me!” And he, in response, raised a finger. Just wait.

Here’s one of the most antique verses of The Oxford Book of English Verse, from sometime before the 15th century:

O Western Wind, when wilt thou blow;

The small rain down can rain?

Christ, that my love were in my arms,

And I in my bed again.

And here’s the chorus of “Tomorrow Is a Long Time”:

Yes and only if my own true love was waitin’

And if I could hear her the rain a-softly poundin’

Yes, only if she was lyin’ by me

Then I’d lie in my bed once again

Had my friend showed me only Dylan’s lyrics on the page, I’d have had no response at all. I’d recognize it as a slightly anachronistic and slightly romanticized re-writing of those old lines into something more demotic, and then I would have forgotten them completely.

The Nobel committee was mocked last year for giving the prize to the little-known Svetlana Alexievich. “Is honor for whole village!” one friend joked to me about it. Other detractors didn’t see her as a creative writer at all: She interviews people and puts those interviews into books. What can be less creative than that?

The good thing about these criticisms is that they can be dispelled by reading her. Far from being a mere transcriptionist, Alexievich is both a medium and conductor for a great folk-wail of Russian grief. Reading her semi-fictionalized descriptions of life in Chernobyl’s contaminated zones, descriptions colored by years of field research and enormous organizational prowess, the reader is made aware of real tragedy in a way newspapers and magazines can only partially communicate.

When you hear Bob Dylan’s “Hurricane” or “Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” you may sing along in real righteous outrage, but the outrage is so often your own, caused by injustice in your own life, and vaguely directed by Dylan at a bad world. When you read Alexievich’s Chernobyl Prayer, on the other hand, the outrage you feel belongs entirely to the peasants who’ve been lied to and mistreated. But, even then, outrage isn’t the only thing you feel. You feel admiration at their courage, bafflement at their stubbornness, contempt at their folk superstitions, and sentimental kinship with their suffering. In short, you feel a complexity of things, and you learn a complexity of things. Just as Dylan’s performing voice brings a complexity of emotion to bear on what otherwise remain static words on the page.

There is much to be said about hybridity, keeping categories fluid, and breaking barriers. On the other hand, there is nothing more tiresome than the undergraduate who spends the whole night saying exclaiming things like “I’d love to see someone dancing about architecture.”

Bruce Wagner has a good deal of fun with this sort of conceit in his novel Dead Stars. The show runner David Simon, a character in the book, continues, comically, to refer to all of his television properties as “novels.”

“David says that his staff is engaged in the writing of another novel that just happens to be in the form of a TV series,” raves a semi-fictional Michael Tolkin to an entirely fictional Bud Wiggins. The latter has always wanted to publish a novel, and now, since he’s sharing story credit for an episode of the new David Simon series, Tolkin’s argument is that he has: “Bud, you are now a published novelist! Or will be, once your episode airs.” Really? “Well, by the Simon definition you are — which I suppose is as valid as anyone else’s.”

When the category of Literature includes everything, it includes nothing. To my mind, literature is represented on the page — making it something the deaf can enjoy as much as those born with perfect ears. And if you’ve written literature that excludes the deaf (or, in David Simon’s case, the blind) have you written literature?

To award the Nobel Prize to Svetlana Alexievich is to award it to a woman who has spent her life working, in obscurity, with the complex materials of literature. To give it to an American writer like William Vollmann, who didn’t even make the rankings at Ladbrokes, would be to give it to a man who has dedicated his life to telling the stories of the poor, downtrodden, and defeated in gorgeous and detailed prose, a prose which evokes the complexities of existence and shares them in conversation with the reader. It would be to call attention to work that needs that attention.

Bob Dylan is a brilliant songwriter and a brilliant performer, but what he is not, even broadly speaking, is literature. Literature is no better than painting or music, no “higher” a form of art, but it is encountered differently, it is processed differently, and it enchants us differently.

Years after I first fell in love with Dylan’s sound, I found myself on a porch in Jamaica Plain arguing with a drunk musician about who was a better writer: Tolstoy or Dylan. I kept rejecting the question: they were too different to be usefully compared. He doubled-down: Dylan, to his mind, was the best living writer because he was more famous than any writer.

But the world has always had music, and it’s always had brilliant songwriters and brilliant performers. They live in the ear, as visual artists live in the eye. Literature lives on the page — a lettered page or a braille page or an illuminated screen. Its words are its only necessary component and so long as we can transmit words we can transmit works of literature.

If the Nobel wants to consider instating new categories for songwriting and visual art, it should. They’re not lesser things than texts. But they’re more than texts, and that has to matter. •

Images courtesy of the author and Ky, Simon Murphy, Xavier Badosa, and RV1864 via Flickr (Creative Commons).