As a teacher of first-year writing since 1987, I have learned to share my passions with students. Sharing what really matters to you can lead to deep learning, but it can also involve emotional risk.

In a class that focuses on using research, writing, and re-writing to think about the connections between literary texts and our lives, I have chosen a theme I think about a lot: Deception. We read short stories in which characters deceive or are deceived. How many of these stories do you recognize?

• A young woman who is very smart in some ways but less smart in others has her artificial leg stolen by a con man.

• A wealthy woman pretends to be a governess for a day and “teaches” using extremely unorthodox methods.

• A woman has an affair during a Louisiana storm and yet it doesn’t hurt her relationship with her husband.

So far, nothing unusual. The emotionally risky part comes from the final assignment: They have to find, learn, practice, and perform a magic trick.

Now, Teaching Police, don’t get excited. We aren’t playing with whoopee cushions and joy buzzers. Magic is a serious pursuit with a long history. Students have to do a research log, with citations, in which they explain how they found the tricks they perform. Students have to do a practice/performance log, in which they discuss the process of learning the trick, document the process of figuring out how they’re going to present it, and think deeply about how they’re going to make people enjoy it. And, yes, students have to get up and do the trick in front of their classmates, and then write evaluations of their own performances. (My colleagues in the university writing game will note that this performance composition process mirrors the writing composition process that we have been working on all year.)

My magic assignment inspires emotions ranging from joy to terror. Adventurous students welcome the whimsical assignment, look forward to learning how to fool their friends, and embrace a chance to do something a little less “school-y” than the usual. Other students are freaked out. What if I drop the cards? What if the trick doesn’t work? What if I look like an idiot?

I appreciate the vulnerability of my students, so I assure them that if they drop the cards they can pick them up and there are many magic tricks that do not require difficult sleight of hand and the class will be supportive in the event of a mishap. Also, it’s a writing class, not a magic class. Most of the grade is based on the written assignments. You can mess up the trick and still get an A.

I try to alleviate students’ fears and help them to take the risks necessary to succeed. But what about the risks I take in giving this assignment?

You see, I love magic. I have loved it all my life.

When I was a boy, I loved when my uncle Phil pulled quarters out of my ear. I loved watching a girl turn into a gorilla at a grind show in Atlantic City. I loved performing at an all-girl birthday party thrown by a 7th grade classmate who kissed me in the powder room. I loved that I could avoid physical confrontations with tough kids by apparently swallowing objects and then pulling them out of my behind.

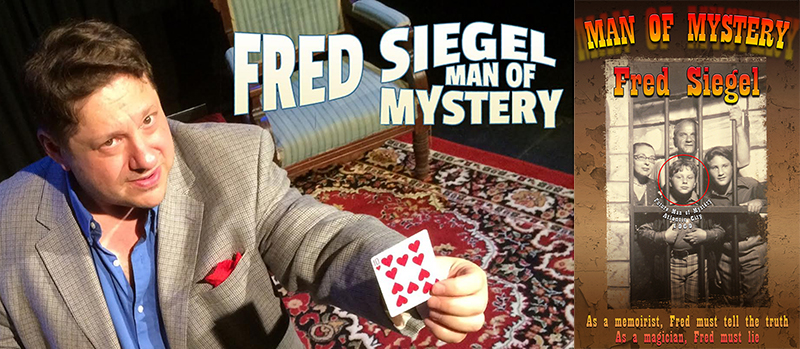

During graduate school, I loved performing alongside a sword swallower and human blockhead in The Coney Island Sideshow, I loved befuddling professors with my blindfold act at school functions, and I loved writing my doctoral dissertation on vaudeville magicians.

These days, I love attending magic shows and conventions, performing the “Fred’s Magic World” theater show with my wife, sister-in-law, and brother-in-law, reading Genii, The International Conjurer’s Magazine every month, developing and performing my autobiographical show, Man of Mystery, and doing card tricks with other magic freaks for hours and hours and hours.

But because magic is absolutely essential to me, there are challenges as well as triumphs with my magic assignment.

The enormity of the internet makes finding tricks to perform easy in one way and difficult in another. Google “easy magic tricks” and you get 4,610,000 results. But how does a student with no magic background choose? Just as they sometimes do in a more conventional research assignment, some use the first source they find and attempt to make it work, rather than spend a little more time and find a better one. In a magical world with many great tricks for beginners, it pains me when my students choose tricks that aren’t fun to perform or watch.

It also pains me to see genuinely interested students attempt to do tricks that are way too difficult for a beginner to master. At the risk of sounding like a cane-wagging old man, this, again, is an effect of that new-fangled internet where all ideas have an equal chance at getting “clicks.” In the digital wild, students can’t always tell if they’re picking a doable first trick or a knuckle-busting sleight of hander. I don’t want to discourage anyone from doing difficult things, but it’s hard for me to watch someone concentrate so hard on their “triple lift” that they are unable to make it clear what the trick is supposed to be.

Also, in a digital world without gatekeepers to decide what is worthwhile and what isn’t, anyone with digital video capabilities can make an instructional video, expose any trick they know, and put it out there for anybody to see. To my disgust, young doofuses who know diddly about magic teach tricks on their webcams to show how smart they are, not to show others how to mystify artfully. In my classes, some perform tricks poorly, even though they are doing it the way the kid in the video demonstrated. (To be fair, some students come in with really good tricks — much better ones than I knew when I was starting out. This, too, is an effect of a free market of ideas.)

All of these research problems are surmountable, of course. I can meet with students, if they have the time, and help them pick appropriate tricks from the digital wilds. I can loan them a book, or I can send them to the public library and look for 793.8 — the most thrilling number in the building, as far as I’m concerned. Or, I can just teach them a trick. After all, consulting with an expert is a legitimate form of research. Students who do that get a dedicated mentor. I can show how to replace a strip-out riffle shuffle with a much easier haymow shuffle and still get the same effect. I can explain that slow and clear is better than fast and crazy. I can explain the tremendous power of looking at the audience and smiling.

So, I should be happy . . .

Well, mostly, I am. But here’s the problem: If students use inferior sources to write an uninteresting essay about the short stories of Flannery O’Connor, Saki, or Kate Chopin, it doesn’t bother me, at least not in a personal way. If they roll their eyes at the prospect of writing a paper comparing food trucks to the school cafeteria, I carry on. If they can’t fix their comma splices no matter how many times I point them out, I can slough it off. Hell, I can even sympathize.

But what if they roll their eyes at my magic assignment? What if they put as little effort as possible into the most enthralling pursuit of my life? What if they just don’t like magic?

On the last day of class, everyone performs a trick. They get an introduction from me, the master of ceremonies, and they get applause upon their entrance. At the end of the trick, students get more applause, ranging in enthusiasm from respectful to genuinely impressed. Students are excited and terrified and supportive and, in more than a few cases, a little triumphant. And even if not all of the magic goes perfectly, the final logs are always fun to read. They reflect learning, even though it might not be the kind of learning that people usually expect in a writing class.

How will they remember magic class? How will they remember me?

Sharing passions is risky. For now, I think it’s worth the risk. •

Images courtesy of author and Cindy Woods, Dani_vr, wiennat, amaniacadored via Flickr (Creative Commons)