. . . Come on! Here is work! Here is opportunity! Here is equality of reward . . . when ‘the world is made safe for democracy,’ Democracy will be made safe for women.

— Dr. Frances Van Gasken, Professor of Clinical Medicine, Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1917

Nearly 70 years after women officially entered the medical profession, they still did not have the right to vote in the United States of America. Though the role and prominence of female physicians progressed parallel to and was sometimes intertwined with the struggle for equality, for many women — those working inside and outside the home — the right to vote was not necessarily a priority. But as women entered professions and the industrial workforce in increasing numbers and the United States engaged in war, American women were undertaking more than ever the responsibilities of citizenship without the accompanying rights.

In the decades after the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848 at Seneca Falls, New York, the struggle for women’s suffrage had repeatedly taken a backseat to other issues. The movements to end slavery, and, after the Civil War and Emancipation, to achieve black male suffrage, dominated the agendas of male and female reformers. By the 1910s, women were eager to fight for their own rights to full citizenship in the world’s largest democracy, often through the organization of various women’s clubs. The Women’s Club movement of the Progressive Era also gave rise to ardent temperance advocacy, maternal and child health initiatives, pure food and milk drives, and other public health issues concerning children and families. In these clubs, women learned public speaking, organizing, advocacy, and publicity skills; but they had no mechanism to enact meaningful policy change without the suffrage.

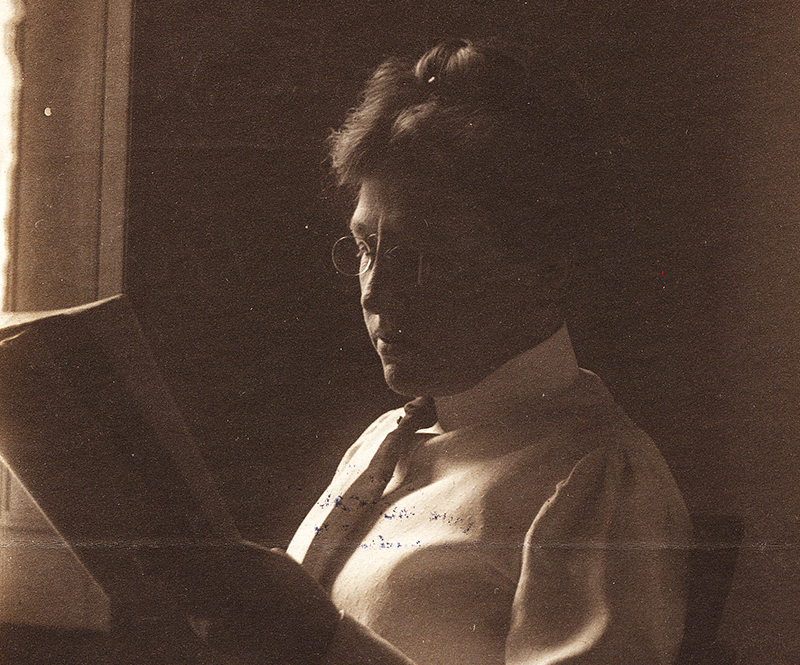

Social and political forces inevitably compelled professional women, including physicians, to lobby for the vote. Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania alumna Dr. Lillian Welsh (WMCP 1889) recounts in her 1925 memoir how the practice of “medical sociology” — essentially, the Progressive-era public health movement that incorporated social and economic reforms — necessitated policy changes that the mostly female doctors and settlement workers could not achieve without the vote.

When social workers, doctors, nurses, and other public health workers appeared to testify before Baltimore City Council about the need for legislation to regulate clean milk distribution in the city, Welsh reports that the (all-male) council was “incensed” at the presence of so many women who were out of their sphere and ultimately postponed voting on the issue. At another city council meeting devoted to the issue of keeping children out of pool halls at night, Welsh recounts that one man commented, “the women are out in force.” His male companion replied, “It makes no difference. They have no votes.”

Welsh concluded that “… women must bend their energies to securing the suffrage before they could hope to make much further progress in making their influence felt on the causes in which they were interested.” Admitting that she hadn’t much thought about suffrage as a student, once she went out into the wider world to work as a doctor, Welsh saw the need for female physicians to be able to effect policy. Medicine could heal, but it could not improve the living conditions or eliminate the poverty of the families she worked with in Baltimore. Only legislation and policy — politics — could do it. To truly make a difference, women needed the vote.

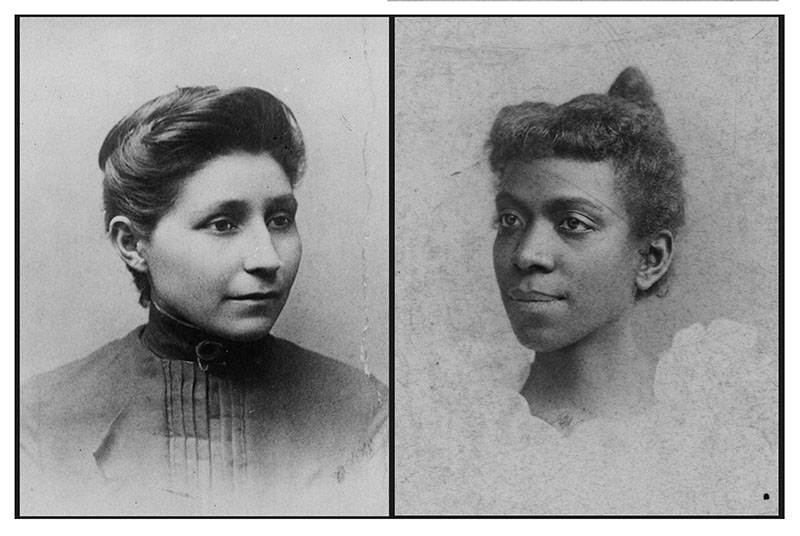

Additionally, female doctors had been modeling professional and economic independence for more than 50 years, building practices, doing research, teaching; with the introduction of the personal income tax in 1913, they became living examples of taxation without representation. Woman’s Med alumna Dr. Eleanor C. Jones (WMCP 1887) linked the economic and political arguments for suffrage in a letter published in the March 1912 issue of the WMCP student newsletter, The Iatrian,: “What about the six million wage-earning women out in the world? . . . America can never be a real democracy until all of the people, whether male or female, participate equally in the Government.”

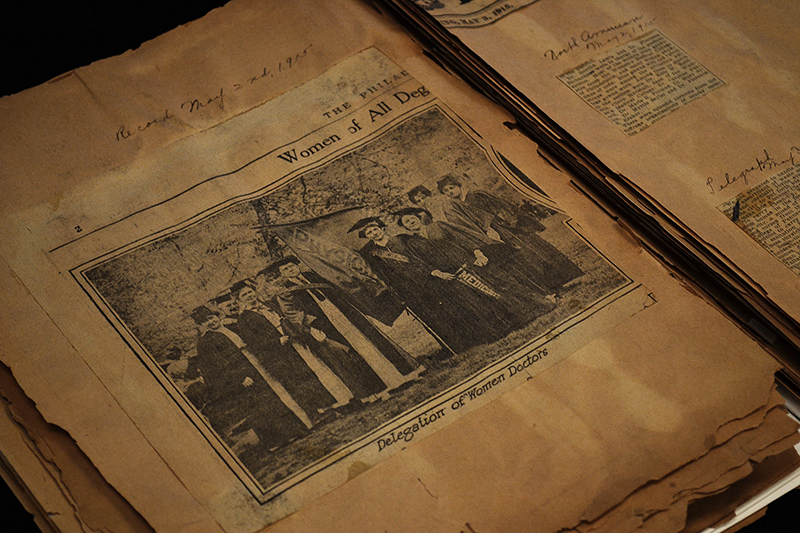

In 1913, the day before President Wilson’s inauguration, 8,000 women paraded through Washington, D.C., bearing banners and signs declaring their rights and demanding the vote. Among the professional groups marching — lawyers, businesswomen, etc. — female physicians were well represented, with WMCP alumnae forming their own delegation. Again in 1915, in Philadelphia, women staged a suffrage march, and again Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania graduates turned out in force. At the 1916 annual meeting of the WMCP Alumnae Association, the female physicians passed a resolution in favor of an amendment enacting women’s suffrage, declaring that “The time is now at hand for us to take such action. The matter vitally concerns us . . .”

The next year, upon the entry of the Unites States into World War I, there was a shortage of workers for all types of jobs related to the U. S. war effort — including physicians — at home and overseas. President Woodrow Wilson’s determination to model democracy abroad was undermined by continuing to deny one-half of the American population the right to vote. Activist suffragists like Alice Paul loudly and publicly demonstrated against this contradiction.

The need for the nation to mobilize for the war effort, and the growing professionalization of women forced the conversation about the role and status of women in the United States. Female doctors eagerly participated in this conversation. Many viewed it as their patriotic duty to use their medical skills during the war to care for both civilians and soldiers. With so many male doctors called away to combat, it seemed obvious to female physicians like Dr. Frances Van Gasken that the United States government would call upon them to fill the need for medical personnel. The war created an unprecedented need for doctors, with shortages affecting Americans at home and overseas in the European theater. Dr. Van Gasken, the director of clinical medicine who was known for wearing a “Votes for Women” button while teaching at Woman’s Med, addressed the incoming class in September 1917: “Who is there to fill these places but women? . . . Is it not your day? Does opportunity not call to you?” When the General Medical Board of the Council of National Defense appointed Dr. Rosalie Slaughter Morton, who had studied the the Scottish Women’s Hospitals in Europe, to form a committee of female physicians, it seemed inevitable that Uncle Sam would soon call upon the Daughters of Aesculapius to join their brothers in patriotic service.

At their 1918 annual meeting, two years after endorsing suffrage, the Alumnae of Woman’s Med passed a resolution:

Resolved, That the Alumnae Association of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania put itself upon record as asking that women physicians be eligible for admission to the Medical Reserve Corps; and, when so admitted, that they receive the rank and pay given to men for equivalent work.

In April 1917, the U.S. entered the war; by June 1918, female physicians were still waiting for the official word from the government asking them to join the military medical corps. In the meantime, they took matters into their own hands, forming voluntary organizations and traveling independently to war-torn areas of France to provide sorely needed medical care for the population alongside other philanthropic organizations like the International Red Cross. WMCP alumni who traveled to war zones in Europe included Dr. Rosalie Slaughter Morton (1897), Dr. Mary E. Lapham (1900), and Dr. Lillian Stephenson (1909). Medical women’s groups serving overseas included the American Women’s Hospitals, formed expressly for this purpose; a unit from the all-female Smith College; the Overseas Hospitals of the National Women’s Suffrage Association; and the Hospital Unit of the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. The latter group served under the French flag, with French Commissions, after its services were officially rejected by the U. S. Surgeon General, Dr. William C. Gorgas. Despite female doctors demonstrating their patriotic loyalty and service, the ultimate goal of securing military commission with rank and pay equal to male doctors remained out of reach.

War has always upended women’s lives: left at the home front to care for their families and returning soldiers in a society where all of the usual economic and social structures have disappeared. But by the onset of World War I, women were poised to play a more active role than that of struggling to survive on the homefront with diminished resources and divided families. Female physicians viewed WWI mobilization as an opportunity and an obligation to participate and make change — and to determine their own fate.

As women proved their mettle as citizens and workers, it became more difficult for politicians to ignore their increasingly public voices and civic actions. By 1917, women had engaged in decades of activism and protest for equal rights and were entering the workforce in unprecedented numbers. Winning the right to vote would reinforce the work that female physicians had been doing at home and abroad, solidifying women’s status as fully capable, participatory citizens. The war years cemented the reality that women were not content to be second-class citizens anymore. In 1920, a year after the Treaty of Versailles ended the fighting in Europe, the United States finally passed the 19th Amendment, granting women over age 21 the right to vote.

Though a monumental achievement, women’s suffrage was not immediately universal: African American and Native American women were still denied the right to vote and to fully claim American citizenship. Four years after the 19th Amendment, the U.S. granted Native Americans official citizenship status through the Indian Citizenship Act. Only then were Native women able to exercise their right to vote, though even after 1924 many were prevented from voting by literacy tests, fees, and other discriminatory and unconstitutional requirements.

Likewise, the passage of the 19th amendment did not ensure black women’s right to vote. The 14th and 15th Amendments granted African Americans citizenship and suffrage after the Civil War, but applied only to men. Many African American women and men, especially in the American south, were denied suffrage for decades through Jim Crow laws which enforced segregation and imposed poll taxes and literacy tests as prerequisites for voting. Though clearly a violation of several amendments to the Constitution, these wrongs were not righted until Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 100 years after the end of the Civil War. As for female physicians, it took 23 years after the passage of the 19th Amendment for the American military to officially recognize female doctors. In 1943, during World War II, the U.S. Military offered Margaret Craighill, then the dean of WMCP, a medical military commission — the first ever offered to a woman. As of 2016, the United States has still not ratified the Equal Rights Amendment — first introduced by Alice Paul in 1923 — which guarantees women equal rights under state and federal law, including equal pay for equal work. Even in the 21st century, American women are still fighting for a more perfect union. •

Images courtesy of the Drexel University Medical Archive and author