My first idea was to compile a brief and brisk user’s guide to recent rock memoirs, a sort of Consumer Reports of the best and the worst, perhaps grading them with an A minus or a C plus, the way Robert Christgau used to do with his surveys of pop records in the once-influential Village Voice. So I started with Keith Richards’s Life, Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, and John Fogerty’s Fortunate Son before realizing that this whimsical vacation in reading was likely to turn into an unfinishable slog. Even as I read Keith’s (A), Bob’s (A plus), and John’s (C minus) revelatory or not-so-revelatory accounts of the rock ’n’ roll life, more kept issuing from the presses. Carrie Brownstein (Sleater-Kinney), Viv Albertine (the Slits), Donald Fagan (Steely Dan), Steve Katz (Blood, Sweat and Tears), Greg Allman (the Allman Brothers Band), Peter Hook (New Order), Bernard Summer (New Order), Brian Wilson (the Beach Boys), Mike Love (the Beach Boys), Nile Rodgers (Chic), Richard Hell (Television, the Voidoids), Kristin Hersh (Throwing Muses), and the drummer from David Bowie’s Spiders from Mars band (Woody Woodmansey): all have had their say, and that’s not even to mention continuing contributions to the genre by such heavy hitters as Bruce Springsteen, Robbie Robertson, Chrissie Hynde, Peter Townshend, Neil Young, Elvis Costello, and Morrissey. Where would I ever find the time to read all of these musicians’ books if I was ever going to read anything else? Or listen to their records? Or vacuum my living room? And then I read Petal Pusher by Laurie Lindeen and decided: the others can wait.

It’s not that Petal Pusher is more “important” or representative than other rock memoirs. Part of its charm is its avowed unimportance. You would have had to be extremely au courant to be aware of Lindeen’s band, Zuzu’s Petals, in their early-90s heyday. But the obscurity of the band turns out to be a virtue. Because there are no well-rehearsed stories about that famous collaboration with Prince or that notorious interview in Rolling Stone, Lindeen can’t count on built-in expectations to sustain interest. The only means she has of sustaining interest is by writing well — which she does, unfailingly, from her unstudied impressions of rival bands (deliciously catty on the subject of Liz Phair) to her almost shocked account of falling in love (with Paul Westerberg of the Replacements, which, as far as I’m concerned, is like falling in love with Mozart). The reader has the further advantage of not knowing what’s going to happen next. Beyond surmising that the story of Zuzu’s Petals is not going to end in a cluster of Grammy Awards, readers are kept pleasantly in suspense as Lindeen drops out of college in Wisconsin, negotiates her parents’ divorce, moves to St. Paul, Minnesota to take part in the burgeoning music scene there, starts up a band, deals with some serious health issues, cycles through a few boyfriends, woodshops, rehearses, composes, hustles, waitresses, and, with her two bandmates, eventually starts sounding like a real musician. Through it all, she writes as the funny, flawed, and self-aware human being that she is, rather than as the rock star she never quite became. Keith Richards’s tales of creating heroin-heavy musical masterpieces in a chateau in the south of France or of stealing Mick Jagger’s girlfriends are a gas gas gas, but they might as well be taking place on another planet. Laurie Lindeen returns from her Zuzu’s Petals tours, in which she and her bandmates take turns driving the van, to resume her eight-hour shifts behind the counter at the Hi-Lo Diner in St. Paul. She’s us. Keith isn’t.

In every rock memoir I’ve ever read, the really interesting part is the upward curve, when the young and hungry artist is in the process of discovering her talent or just hanging out with other hopefuls and sharing the dream. The first flush of success is a buzz for the reader no less than the musician. After that, when stardom succeeds struggle, the air tends to go out of the writing — and sometimes of the music. Is success really that boring? I don’t know. I’ve never had any. Zuzu’s Petals never found out either. They certainly enjoyed the upward curve for a while, nowhere more ingenuously evoked than when a replacement sits in for the departed original drummer and Lindeen and her bass player Colleen discover what every band eventually finds out — it’s the drummer that matters:

Co and I cannot believe the difference that Linda makes. Instead of an interesting independent rhythm, an added texture to our churning songs, there’s a consistent beat holding it all together. Playing is easier with this luxury. Co and I stare at each other, our eyes locked in disbelief. We’re both thinking the same thing: OhmyGod, this is amazing.

Fortunately for the reader, the addition of an accomplished new drummer fails to propel the band into regular rotation on MTV. They rehearse, they tour, they write more songs, they pick up a small but devoted following, they generate some favorable press, they make a promising debut album, and then it’s back to the Hi-Lo Diner. In fact, the whole rock star thing comes to look increasingly dubious to Lindeen, especially after she meets Westerberg, who, as it happens, is a rock star. He just doesn’t act like one. Though constantly harassed with patronizing and sexist questions about her famous boyfriend, Lindeen can’t help gushing about him. No wonder. He’s a dreamboat:

He drinks his coffee with half of the caffeine taken out. He eats fresh fruit every day. He retires around 10:00 p.m. and wakes up bright and early to either walk or bike around nearby Lake Calhoun. He works out on a Nordic-Track. He writes and records music at home all day with an unswerving work ethic and unbelievable self-discipline. He grocery shops and cooks. He takes long, candlelit baths and reads Swami books. He meditates and reads. He quit drinking and drugging yet is still fun.

Little or nothing of this description applies to Lindeen. By her own admission, she’s prone to negativity, she bolsters her self-confidence at the expense of others, her humor sometimes crosses over into cruelty, and she’s still taking cocaine when she really ought to know better. And yet these instances of damning self-appraisal fulfill George Orwell’s dictum that “autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful.” Not that Lindeen is notably more disgraceful than the other musicians and fans and promoters and DJs and hangers-on that she meets in clubs and bars and sleazy hotels. She’s just a work in progress, like any of them — or us. If she gave a thoroughly good account of herself, as Orwell says of any memoirist, she’d be lying.

Lindeen does distinguish herself in one signal capacity: She writes better than most people, including most memoirists. Towards the end of the book, when the grind of touring and promoting has begun to wear down everyone in the band, she submits to a rock publication an essay titled “The Many Faces of Zuzu’s Petals, or Sybil Does Dallas” and discovers that she hasn’t “had as much fun creating in years.” It’s a lovely way to end the book; instead of writing — maybe — a few more pretty good rock songs, she’s going to write a very good memoir.

One of the things you get from Laurie Lindeen that you do not get from Keith Richards or Bob Dylan or John Fogerty is a sense of the wearying difficulty of being a woman in rock ’n’ roll. For a culture that supposedly represents rebellious, anti-establishment values, rock ’n’ roll is about as progressive as the National Football League. The more enlightened of their male associates tell Lindeen and her bandmates, “You guys really rock for girls.” The less enlightened call them “cunts.” True, the men the band meets on their tour of England call everyone cunts, but that only adds to the general atmosphere of squalor that has started to become, for the three exhausted musicians, seriously depressing. Although the sexism is more overt in England, it’s everything the band has always been up against:

I’m not sure what shocks me more, hearing “cunt” constantly, which feels like a blow to my stomach every time my ears try to digest it, or the way we’re being treated. I can’t tell if it’s because we’re American, or drinking pints, or in a rock band, but we’re being treated like Nancy in Oliver! Nancy was a common whore, a murdered common whore. “Fat,” “spotty,” and “ugly” are a few of the other words that are being slung in our direction. We’re not even fat, just not skinny.

Fortunately, the band can count on the support of their English publicist, a raffish charmer named Jimmy B., who has a reassuring reply to Lindeen’s concern that hyping Zuzu’s Petals as drunken bimbos might not be the best of all possible career moves. “Sod off, cunt,” he tells her. “You don’t know a thing about getting the proper attention you need to make it in the U.K.”

No thanks to Jimmy B, Zuzu’s Petals catch on in a small way with the British music press, but when recognition slowly comes, it’s too little and too late. The band is pressured into recording a disastrous second album before they’re ready, and they never acquire the lead guitarist they need to make things really click. To her chagrin, Westerberg obligingly supplies the templates for the solos that Lindeen can’t quite pull off without some assistance. Nor does she like what she sees in the mirror:

John Lennon once said in a Playboy interview that in order to make it in the music industry, you have to be willing to be a complete asshole, a total jerk, a cold ruthless bastard. I think I’m getting close to achieving all of those requirements without the stardom.

So it ends. I’ll always appreciate “Cinderella’s Daydream,” “Johanne,” and a few other songs from Zuzu’s Petals’s first album (tuneful grunge rock with nice harmony singing, if you’re curious), but I appreciate Petal Pusher more, and if Lindeen hadn’t pulled the plug when she did, she might have been too jaded to write it. Other rock memoirs give you the blow-by-blow of the creation of this great album or the discovery of that revolutionary sonic effect, but in a way, Petal Pusher is no less triumphant. It shows an ordinary woman becoming fully and lovingly human by getting the hell out. •

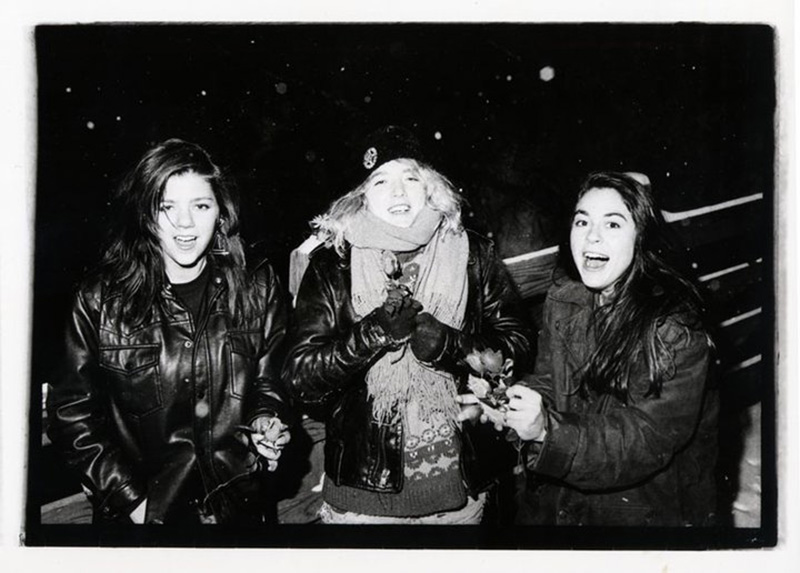

Images courtesy of Laurie Lindeen and benguil via Flickr (Creative Commons)