I could die. Me. Personally. Could. Die. Well, I sort of always knew this, but remotely, so remotely, in the manner that we acknowledge, and with the same measure of anxiety, that someday the sun will flame out. But now — revelation! — I suddenly realized I actually could die — like at any moment.

This knowledge is what has propelled me into engaging simultaneously in two genres that I fundamentally loathe: the memoir and the medical essay. Along with my traditional reporter’s disdain for employing the anorexic pronoun, I believe that unless a memoir is written by an extraordinary individual — Augustine, Springsteen — I see no point in inflicting a memoir on readers. And I surely do not number myself among the extraordinary. Indeed, one of the things that drove me out of academia was when my English Department introduced a course on writing memoirs; the notion of 18-year-olds doing so is worse than cringe-worthy. Read the story of someone who has lived an exceptional life? Sure. Read stories of the pimpled masses who have not lived any lives whatsoever? Better to read the conditions you must accept before installing your latest app.

Thus, I’ve always been decidedly against writing a memoir. Much in the same vein, I am opposed to illness and against death. And if all that sounds — what’s the word? stupid rears up and will do nicely — if that sounds stupid, it’s a certainty that no wisdom will arise from this essay. My observations on these most common of human experiences — illness, dying, and death — are going to be commonplace. My conclusions will be banal. The best I can hope to offer is, oh, maybe a mild and momentary diversion.

Still, if I’ve lived an unexceptional life, I’ve lived a fair amount of it, almost the biblical three score and seven years or whatever it is. Which means that virtually all of my social circle is comprised of septuagenarians. Which means in turn that whenever we get together the inevitable early topic of conversation is health, or more precisely the lack thereof. This one’s heart condition, that one’s blood pressure, the other’s joinery repairs and replacement (often in confounding multiples), yet another one’s stent. I don’t know what a stent is and don’t want to know. In fact, I always tune out these cheery and competitive kneecap recaps, pacemaker adventures, blood count bidding wars, rotator cuff narratives, physical therapy descriptions, pharmacological comparisons, and the like until I can bear no more and chivvy the crowd onto some happier topic, like Aleppo or the Fed. In the same manner, I out-tune any report on radio or TV, online, or in print about medical matters, or worse, medical “breakthroughs.” Show me the word cancer and I’ll show you the door. I can’t bear any of the stuff because I can’t in the least relate to it, no more than I can take up an interest in curling or Mongolian throat-singing or the internal politics of New Guinea. Yes, I know I should be interested in everything, even things that don’t interest me. But one hasn’t world enough and time to absorb the entirety of the world any more than one can read all the world’s literature.

All of the above of course reveals a certain measure of denial on my part. Yet I can’t relate to my friends’ medical problems or published health bulletins for the simple reason that I have never had anything like a serious medical problem of my own. Let me repeat that: I have never had anything like a serious medical problem of my own. Certainly, nothing that wasn’t easily manageable. Sure, I’ve lost a few teeth, and I’ve had cataract surgery, but these aren’t worth mentioning, so I won’t. Oh, I was told some time back that I had diabetes, but these days what American hasn’t? Just about everyone in my family had it, so why not me? I pop some pills, that’s all. I barely give any of these ailments any more consideration than I would a fleeting ice cream headache. Why should I? Look, I’ve never spent a night in a hospital. I’ve never been prevented from performing any physical activity. I have never once missed a day of work for illness. (Drag the cold to the office, pass it on to some unsuspecting intern.) I’m built like a linebacker. I always remember where I’ve left my keys. (Um, where did I park the car?) Sure, I’m getting older, but everyone is, right? I’m losing my hair, but why should that suggest I’d ever be losing my life? Aging is natural, inevitable, but for me, it’s also been so subtle, so slow, why should I ever associate aging with expiring? Where’s the connection? What about redwood trees, huh, huh? Sequoias, amoebas, they just go on blithely aging forever. Why shouldn’t I?

Okay, I’ve been adolescent all my life about health, dying, and death. But truth is, aside from the occasional outworn tusk or ocular cobweb, I have hardly sensed aging whatsoever. When I turned 70 I sincerely believed I was as vigorous as I was at 50, and maybe even at 30. Denial? I deny that. I had abundant evidence to support my enduring durability.

Until, that is, late last year.

It hit the fan and did it ever. It began with a mild and periodic discomfort in my abdomen. This was most peculiar; I had never experienced anything like this before. When my GP asked me to assign it a number on his Hippocratic-Richter scale of pain I declined to give it even a one. It was merely a visiting intrusion, I insisted, in my otherwise cast-iron innards. Still, the abdominal annoyance was strange. It wasn’t me.

Soon enough, however, my minimalizing and disclaimers no longer applied. Over the ensuing months, the visitations became more frequent and were accompanied by blood sugar measurements that were all over the map. I moreover experienced an unaccountable loss of appetite and pep. For the first time ever, I was unable to finish what was on my plate. Loss of weight inevitably occurred, in the tens of pounds. Eventually, I was punching new holes in my belts, then serially downsizing my trousers. I was the envy of all my overweight acquaintances, which means all of my acquaintances, and I was repeatedly told that I “looked good.” Well, yes, I looked trimmer. But I felt crappy.

So began the rounds of “tests.” Colonoscopy, endoscopy, chest X-ray, stress test, C-Scans, MRIs, blood analyses, I can’t name them all because of course, I did my utmost to maintain ignorance. Manfully, I sustained a state of induced obtuseness. But even so, I realized that while my GP studiously avoided the C-word, I suspected that he suspected some variety of cancer. How else to explain the debilitating weight loss? I must be eating myself alive.

One thing was becoming self-evident: in such a circumstance, I could die.

Indeed, as my symptoms worsened I became convinced I was dying. I told myself that this surely is what dying must feel like: like the Marxian state, an inexorable withering away. Despite what my friends might claim, I did not “look good.” In fact, for the first time, the face being shaved in the bathroom mirror in tandem with me was clearly the mug of an old man. And not just an old man, but an old man on his way out.

Now death has always interested me — like a true intellectual I think of it every day and always have — but it has never frightened me. I’ve long thought of my state after life quite like the state that preceded my birth; two unknown and unknowable states barely worth speculating about. Something like the states of North and South Dakota. Or perhaps not. But unlike death, dying is something entirely different. At the very least, dying, and especially enduring a prolonged demise, is disruptive both to the subject and to those around him. Dying presents predicaments. Renew the subscription to the New Yorker? Make dinner plans? Make any plans at all? What a nuisance. But at its worst, kicking the bucket can really hurt your big toe. By which I mean dying can be painful. The prospect of terminal agony is scary and depressing. And I was starting to suffer.

Then came the lump. One day I noticed a swelling in the lower right side of my groin, one of my most cherished areas of my anatomy. Didn’t hurt, wasn’t even sensitive. Hmmm? Next day it wasn’t there. Next day it was back. And so on, until I couldn’t ignore it any longer. It was as if I’d absentmindedly swallowed a doorknob that somehow got deposited in a very undignified destination. But I was pretty sure what it was. My father had had testicular cancer. Acorn from the tree.

My GP palpated my tenderloin and declared no cancerous growth, just a hernia. A hernia? A hernia from what? I thought you got those from shifting pianos or boosting bank safes. I was an intellectual, I protested, I work sitting down. Often lying down. Heavy lifting was not in my job description. No, the doctor explained patiently to the patient, you don’t need to suffer a trauma to earn a hernia; it can just happen. Easily repaired, he added. Here’s the name of a surgeon.

Surgeon? Now there’s a professional title to conjure with. Up there with CIA interrogator, IRS auditor, executioner.

Despite my dogged avoidance of medical information, I went home and Googled “hernia.” Revolted, I quickly unGoogled.

I met the surgeon and took a seat in her examination room, situating myself so I did not have to look at her obscene wall chart of the gastrointestinal system. (There is an excellent reason why God put our innards inside and out of sight.) The cutter examined me and announced my problem could be routinely set right with a small incision and the insertion of something like a miniature badminton shuttlecock. She held up one such elvish plaything and offered it to me for hands-on inspection. Ever in denial, I declined the offer. Like a proud grandmother, the surgeon then brought out an album of colorful eight by tens of her greatest hits. I did my best not to look. The only upside to all this was learning that the procedure was considered “minor surgery” and that I would be in and out of the seamstress’s workshop in a few hours. My record of not spending a night in a hospital would remain intact, even if my beloved groin would not. And so it came to pass.

But wait — my weight loss, lack of appetite and energy, abdominal ache — all that was the result of a stupid, mundane hernia?

Of course not. No, the hernia was just a little interim joke on God’s part, a wink and a giggle. Think you can ignore your aging body, eh, the Deity seemed to be saying. Think again.

Indeed, by the time I was shuttlecocked and stitched back together the medicos and the technicians — the tests! the tests! — had determined that I had calcifications on my pancreas and that one sizeable gemstone, in particular, was blocking the organ’s exit duct. Yet the experts weren’t certain that even this was responsible for the weight loss, or the lack of appetite, or the see-sawing glucose count, or the pain. And they weren’t certain what should be done. They weren’t certain about a lot of things, which is not consummately reassuring. They had a number of possible procedures up their sleeves but essentially adopted a wait-and-see attitude. Come back and see us in three months.

I was more than a little annoyed. Barnacles on my pancreas? Why couldn’t I get gall stones or kidney stones like everyone else? None of my friends had ever heard of stones in the pancreas. I Googled. I unGoogled. Whatever was going on, I had the dubious distinction, at least among my circle, of being a medical curiosity.

Another novelty for me was that soon my “abdominal discomfort” had graduated to genuine and unignorable pain. Came Thanksgiving week — superior timing — and I had never felt so rotten in my life. At dinner, I managed something like half a wing. Next day I called the gastroenterologist’s office and suggested three months was too far off for my next consultation. Got a more timely appointment. But not timely enough. Next night, quite convinced I was if not exactly at death’s door then at least in the lobby or the elevator, I checked my miserable self into the ER.

Hospitals. I had a thing about hospitals. As noted, I had never had need of hospitalization, but I’d visited plenty of patients; after all, my friends were all aged. Thus nothing prevented me from imagining my own self-hospitalized. More accurately, I could not imagine how I would endure the experience. Consider that for over 50 years I have been a fanatical pipe smoker. (Dr.: “How much tobacco do you consume?” Me: “Um, as much as possible?”) The odd thing is I can endure a stretch sans pipe; I once flew 14 hours to Beijing without, to my great surprise, the desire to hurl myself out of the plane, briar defiantly smoldering between my teeth. But if that was fairly remarkable, it was still a mere 14 hours, abetted by booze. Could I face whole consecutive days and nights in a smoke-free medical facility and were the only shots on offer were administered via syringe? Damned doubtful. And then there’s coffee. Years as a newspaper night editor have me firmly habituated even in retirement to 10-12 cups a day. Yes, I’m addicted to caffeine, but so thoroughly that I believe I am also caffeine-immune: I can — and usually do — drink a couple of cups right before retiring and sleep soundly all night.

I acknowledge tobacco and coffee as vices and ultimately “not good for me.” But remember, I’m essentially an adolescent. Definition: the age in which one goes rappelling without a safety harness. And I’m certain there are worse vices. And as soon as this balding teenager figures out what they are, he’ll probably take them up.

Meanwhile, other hospital horrors horrified me. Visiting friends, I’d been exposed to them all. Being confined to a bed — and maybe to a bedpan. Being wired up like Frankenstein’s monster. Enduring the beeping monitors — like being aurally assaulted all night long by a reversing garbage truck. The hospital smell. The doctors, all named Walid or Ismail and secretly dedicated, despite their credentials, to the destruction of Western civilization. Being woken up for sedatives. The tests and the tests. Daytime television. The smirking, mysterious nurses, each one called Brittany and each wearing identical, squeaky, rubber-soled shoes. The confusing white coats. (Physician? Intern? Nurse? Janitor? Embalmer?) Wonky WiFi. The inedible, unidentifiable meals. The icy stethoscopes, the death-grip sphygmomanometers, the thermometers in the ear (the ear?), the electronic clothespin on the index finger, the syringes, other assorted meat probes. The traffic jams of wheelchairs, walkers, gurneys (morgue-bound?). The irremovable ID wristbands, as if issued for admission to some chthonic dance hall. The medical students crowding around the bed and considering you as an interesting sack of spoiled viscera. The humiliating hospital gown. The stupid gift shop balloons. The crying children. The dying children. The artless landscape prints on the walls. The cloying flowers in their tin water pitchers. The granny bed socks. The visitors so obviously burdened by visiting. The patient moaning in the neighboring bed with AIDS, Ebola, Zika, God knows what. The oleaginous clergyman dropping by. That most horrific of medical devices: the catheter. Wait, I can top that — the colostomy bag. The waiting and waiting — and for what? The bedridden boredom. The total surrender of will and independence. The indignities. The infantilization. The utter helplessness.

Above all is the indisputable fact that a certain number of patients enter hospitals and fail to exit them alive. Such was the case with my older brother.

Did I write “older brother?” I am now older by several years than he ever was. I have also accumulated more years than my father did.

These facts have given me pause countless times.

In truth, I was pretty old. And now I had the distinct impression that I was dying.

So what more appropriate place for extinction than a hospital?

But to be extinguished or not, how could I ever endure such an environment? I readily told myself I’d rather suffer, wither, die at home, with my boots on, and not wearing some clinic’s granny socks.

But life, and I suppose death, is full of surprises. From the ER I was promptly transferred to the hospital proper, and the hospital proved to be more than endurable. The bed, where I spent four and a half days, was unaccountably comfortable. The personnel were all pleasant and solicitous. The room — and my roommate — were quiet and tranquil. The food was largely inedible because I was placed on a “clear liquid diet,” which was explained as food I could look through, although why I would ever want to view the world through my food was never explained to me. Yet the beef broth was actually tasty. Surprisingly, I did not in the least hanker for my pipe or my coffee, which I attribute to being so pharmacologically zonked and discombobulated that I didn’t know any better. Best of all, I didn’t die. Instead, I had my “procedure,” in which my pancreatic rock was endoscopically kicked free. I’ll spare you any details because I gathered none. I was blessedly anesthetized during the whole thing, and afterward, I remained devoutly incurious about all things medical. And before I knew it, it was one last beef broth, and I was signing for my release.

I had been hospitalized and now I was dehospitalized, and like so many experiences — final exams, army life, job interviews, marriage — being a medical patient proved not nearly as fearsome as I’d feared. Unpleasant or not, we get through life’s vicissitudes; what alternative do we have? Two days after returning home I was cleaning my gutters and blowing leaves. I felt better than I had in months. It was a staggering, damn near instantaneous recovery. It was unbelievable. I sent congratulatory e-mails to the doctors. I reported enthusiastically to everyone — friends, the UPS guy, folks in line at the supermarket. I was no longer dying. I was living.

One thing, however, was different. For the first time in my life I inhabited the knowledge that although I was not dead, I still could really and truly die. Okay, would die. All right, will die. I’d had a taste of dying, and although I hardly savored the taste I didn’t resent it. Indeed, it had taught me something of supreme value. And yes, here comes the culminating banality of this essay, the promised mundanity, the oh-so-predictable commonplace. It’s this: having encountered, or at least imagined, a near-death experience, I now understood that death was ever hanging out around the corner. This meant that every day now in which I manage to wake up and am not dead, I am profoundly grateful. At my age and with unknown frailties and vulnerabilities simmering beneath the surface of my robust exterior, I truly understand for the first time that I could die at any moment. And because of that hard-won knowledge, I am now more appreciative of being alive than I’ve ever been before. Well, no, I’d never in the least appreciated it before. But now all that is changed. Now I’m grovelingly grateful for every new day. I know, I know, this sounds like just so much inspirational Hallmark Card-embroidered homily-Lifetime TV-self-actualization crap. You bet it is. But if it’s crap, it’s my hard-earned crap. It’s my revelation. I’d always accepted my vigorous health as my due — in perpetuity. But today I know better, much better. That’s the difference.

Of course, I’ve also immediately resumed sucking my pipe and slurping my java. I didn’t learn every life lesson.

But I have embraced the crowning cliché: Be thankful every moment of your lowly, inconsequential existence. I know I am. Oh, you mean live every day as if it were your last? Absolutely, because one of these days . . . And if that sounds banal, well, let’s face it, so is death. So face it. The fact remains that existence is a limited-time offer. Take advantage, enjoy it, relish it — while it lasts. •

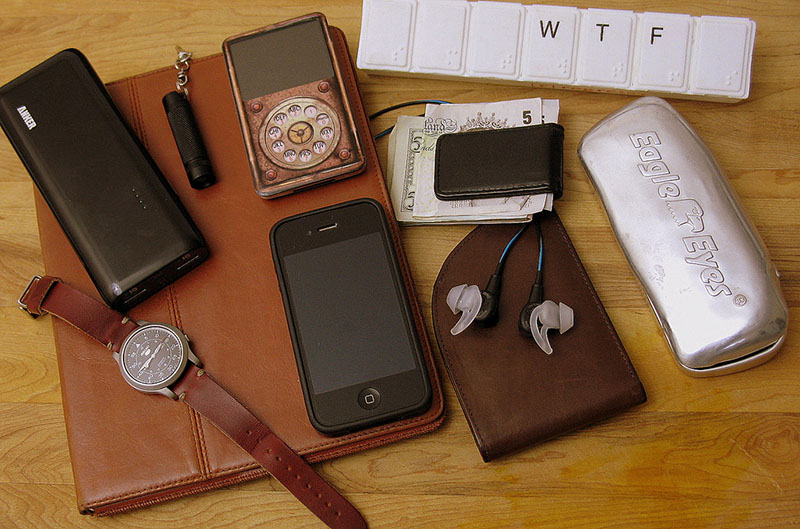

Images courtesy of irihiyahn-percussion, txinkman, ryochiji, a.drian, ISOtob, and shannxn via Flickr (Creative Commons)