My dissertation was about women’s authorship and sitcoms. Authorship is a key word here. It wasn’t about “writers,” but about those who left their marks on the text, their control over character, storylines through aspects of performance and utilizing their star power — for most of my case studies (30 Rock, Girls, and United States of Tara) the examination did focus on writing, but what I found while returning to the archives was the thread of women’s narratives that dealt with writing without words. Lucille Ball never wrote for I Love Lucy nor was she the head of Desilu, but as Madelyn Pugh Davis, one of the show’s writers, notes in her memoir Laughing with Lucy, Ball exerted authorship through performance and her refusal/approval to perform certain scenes. Amy Poehler wrote a handful of Parks and Recreation episodes, but her iconic status in improvisation as a founding member of Upright Citizen’s Brigade and successful sketch career at SNL brought her a certain level of authority to the series, a sentiment continually asserted in interviews with the cast and crew. Mary Tyler Moore is also part of this legacy of women’s negotiation and “writing.” She wasn’t a writer but owned her performances. She owned her brand and in doing so provided opportunities for writers to develop their own. Mary Tyler Moore owned Mary Richards, who helped women figure out their place in feminism’s upheaval of roles and norms.

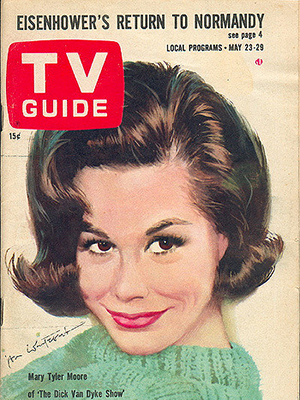

I watched a lot of the Dick Van Dyke Show when I was younger. I don’t know why — I can’t name the channel and this was a time before the mass circulation of TV seasons on VHS and DVDs. Throughout its five-year run, the show didn’t recruit any female writers, but it was one of the few to acknowledge that female writers existed with its representation of Sally Rogers (Rose Marie), who was contradictory in the sense she was aggressive in obtaining her position as comedy writer but was also frequently looking for (rather desperately) a marital partner. In some ways, Mary Tyler Moore’s Laura seemed her perfect foil. Less brutish than Sally (she made dirty jokes and grotesquely contorted her face), she was gorgeous and feminine. But as much as Laura was Rob’s wife, she was not docile and certainly not not submissive. In fact, for the time, Mary Tyler Moore’s character was a bit controversial. She didn’t wear a dress and pearls. She wore cropped slacks tight enough advertisers were concerned, but they conceded to the costuming as long as they didn’t cup her ass. And according to Moore’s memoir, this was her choice as she snuck in the pants into production, stating in her memoir that she wanted to represent women realistically as opposed to idealistically.

But in some ways, Laura was still an ideal, because Moore was an ideal. Laura was a young wife and mother. Her husband was in show business, which gave her access to celebrities. She was white and middle class. And Laura was Rob’s partner — they were a couple who didn’t seem like a contract marriage, one made out of convenience; rather, they actually liked each other. Their marriage was full of play, touching, and communication. They taught each other lessons through practical jokes that were rarely mean, all aimed toward helping the other become a better partner. Moore was able to make a common type (the housewife) more complex. She was fragile and yet resilient. She often cried on the show, but it was rarely unwarranted or overdramatic; in fact, her tears came in spite of herself. It was Moore who authored the performance and Moore who created an idealistic reality for young mothers in the 1960s.

It would be erroneous to imply this period of television’s history was full of equality — it’s not that the writers were strictly aiming to create a show featuring empowered women. I doubt they were — actually, I think Rose Marie and Mary Tyler Moore helped develop these characters in ways that took them beyond stereotypes and the butts of jokes. Even in one of the most progressive eras of television, the 1970s, women were searching for places on and offscreen. Diana Gould formed the Women’s Committee of Writer’s Guild in 1971 to try and better network and help find opportunities for women — more collective action, more work, and hardship. There were few working female writers (at least in comparison to male writers), but those who were present were organizing and pushing themselves through the doors and ready to politicize comedy television. Two organizations helped amplify this sentiment: Norman Lear’s production company Tandem and Mary Tyler Moore’s MTM.

Like Lucille Ball before her, the production company bore Moore’s name, with her husband at the time, Grant Tinker, taking an executive role. Established in 1969, Moore and Tinker’s company helped define 1970s television with The Bob Newhart Show, WKRP in Cincinnati, and, of course, The Mary Tyler Moore Show. The latter ushered in “the new woman” of the 1970s, one influenced by the feminist movement and hope of economic independence. Mary Richards (Moore) left her life of domesticity and the hope she had placed on what would have been an ideal mate — a future doctor. The show was about Richards establishing herself as a single person. But again, Moore wasn’t ideal. She wasn’t a perfect feminist. She struggled to figure out her place in this new society with new ideals. She tried to find her place and her voice. But in this struggle, she carved a space for us to laugh, for women to find humor in the anxiety of figuring out new roles and expectations. When it ended, writer and director Nora Ephron reminisced in Esquire “. . . all I want to say, and without being too mushy about it, is that it meant a lot to me the second time I was single and home alone on a Saturday night to discover that Mary Tyler Moore was at home too.” Despite Richards being a single woman, she wasn’t lonely. She had her work family, but also a group of supportive women like Rhoda and Phyllis, emphasizing the the support one can feel among women and in friendship networks. And the fact, Moore, the producer and star of the program could share the space with women like Valerie Harper, Cloris Leachman, and Betty White demonstrates a significance placed on building women’s presence on screen, of supporting each other, and understanding that showcasing others’ talents does not necessarily depreciate our own.

Mary Tyler Moore wasn’t necessarily an activist in the way we typically conceptualize. She didn’t have the reputation Roseanne gathered for fighting back against executives, she seemed to negotiate her identity as opposed to fight for change. But she did carve a path for herself and others — she provided a model of confident femininity even when that identification was in flux. While working on my dissertation and revisiting those episodes of The Dick Van Dyke Show and The Mary Tyler Moore Show, I was struck by how relevant these narratives continued to be, and even more so how relevant Richards was — her life as news producer coming through to me, a graduate student teaching courses. I was in my mid- to late-20s trying to figure out where I fit — what kind of feminism aligned with my viewpoint of the world, how I could stay true to myself while also working collectively and compromising, and how to get shit done while in spite of others’ dragging feet. Moore’s characters and performances transcended time — even now it’s hard to find other TV women who are able to balance idealism with the reality of women’s everyday lives.

Moore’s impact on television has been overwhelmed in part by Norman Lear’s legacy, but it shouldn’t be forgotten. Moore’s ability to weave high and low culture, own her characters, and represent women’s lives in ways that were funny and complex is still something Hollywood studies have difficulty accomplishing and something that more than ever is necessary. We can thank Moore for those who came after her — for the Roseannes, Rachels, and Carrie Bradshaws who would present models for femininity that allowed for mistakes and aspirations. •

Images courtesy of Jim Ellwanger and m01229 via Flickr (Creative Commons)