The name Ganja Acid combines the recreational sloth of marijuana with the cosmic distortion of the 1960’s most iconic chemical without offering any hint that it belongs to a four-seat psychedelic bar. A friend suggested my wife Rebekah and I visit it while on our honeymoon in Osaka. Although I no longer smoked weed or dropped acid, I still loved the psychedelic: surreal books, occult verbiage, hippie satire, and trippy music that sounded like it was made on mushrooms. They were fun and reminded me of the risky excitement required to warp reality in order to examine it. The thing was, neither ganja nor acid were legal in Japan. While marijuana shops had popped up all over Portland where we lived, over there, even the smallest amount of weed brought first-time offenders a minimum of five years hard labor.

Japan’s 1948 Cannabis Control Act outlawed the commercial cultivation of hemp after WWII. Because modern pharmaceuticals have recreational uses, Japan also outlawed the unauthorized possession of many opioid painkillers like codeine and banned amphetamines like Adderall that are used to treat ADHD. It didn’t matter how commonly they were prescribed in other countries. It wasn’t a matter of clinical efficacy. The laws treated them with the same firm hand as heroin and cocaine. In June 2015, a high-level Toyota Motor Corp executive was arrested for having 57 oxycodone pills hidden in a package, mailed to her Tokyo hotel from the United States. Authorities held her for 20 days, and, after she resigned her high-profile post, and after she was widely discussed in the media, they let her off without formal charges. This is common in Japan, where the process is often the punishment for people who apologize and express remorse. Although oxycodone was legally prescribed there, the exec didn’t have a prescription and she didn’t get official governmental approval in advance.

126 million people live in Japan. In 2014, 13,121 people there were charged with drug crimes. 768 were foreigners. That means that only 12,343 of Japan’s 126 million citizens got busted for drugs. In America in 2012, the FBI reported 1,552,432 drug arrests. Alcohol is Japan’s drug of choice, of course. The first record of the Japanese people dates to a second-century document called “History of the Kingdom of Wei,” and describes people who clapped and bowed at shrines and loved to eat fish and drink booze. They still do.

The same year as the Toyota executive’s bust, the Kyoto police raided a 17-year-old’s bedroom after receiving a tip about his furtive weed-smoking. Converging on his family home like they were breaking up a smuggling ring, the cops found a small stash and a pipe.

This made me nervous. What did people do at Ganja Acid? What if the cops raided the place during our visit? Besides photos and some bad blog posts, very few details were available about it in English. From what I could tell, despite the name’s law-breaking bravado, Ganja Acid wasn’t a drug den or dealership. Oddballs and touring musicians went there to drink and listen to indie music. Some dude regularly drank in different plush animal costumes; I’m not sure why. Bands seemed to play there and DJs threw parties, which confused me: I thought it was a four-seat bar? Some photos showed a large club. Others showed a dark enclosure. That’s all I knew tell for certain. It left me wondering what weed meant to people who couldn’t smoke it and what acid meant for a psychedelic bar who played psychedelic music written by musicians who might never have taken psychedelics.

So one Saturday night the day after we arrived, Rebekah and I wound down narrow look-alike streets in Osaka’s congested center, past the legendary Time Bomb Records, past a litany of lively izakayas and yakitori joints filled with people drinking highballs from matching Suntory glasses, and there it was, as described: an odd triangular building made from concrete, covered with air conditioning units, set on the corner of four intersecting streets. In America, we’d call these “alleys,” but in Japan’s tight urban squeeze, they passed for streets. Japan did a lot with limited space.

We climbed the stairs and walked the third-floor corridor, past other closet-sized bars with no windows, and found a sign that said “Ganja.” We didn’t hear music from outside. We didn’t hear any noise at all.

I pulled back the door and cigarette smoke rushed out. The door closed and sealed us in darkness. Inside: four stools. The only other patron sat in one, and the bartender stood up behind a counter that was cluttered with what, in the faint light, only registered as a bunch of shapes: curved glass vases, paper concert flyers, dangling things. I couldn’t tell. The young man on the stool casually turned to see who’d arrived. Calm electronic music played, a wash of slow twinkly guitars and harmonized synthesizers. Rebekah and I inched between the wall and counter, fumbling to see any obstacles. It was barely 9:30 — not that you could tell. Inside, it was midnight.

She took the stool at the end. I scooted one back so I could lean against the wall beneath a yellow t-shirt. The guy beside me nodded hello and drew on a cigarette. A black pack of Peace brand sat on the counter between us. “Tiny cigarettes,” I said.

He said, “Unfiltered. I like them the best. Would you like one?”

I thanked him and said I would love one, but I must resist. “I had to quit.”

He said, “Sorry about that,” and tapped ash into a dish. He was in his early 30s, wearing a white t-shirt with short black hair. In the darkness, he seemed tan. Lots of people in Osaka seemed tan.

“Hello, hello,” the bartender said. “Drink?” He stood tall and had longish hair. A floppy, low, wide brim hat hid his features. He had cannabis beer from Germany, three Japanese beers, and Budweiser. “900 yen,” he said, “that’s okay?” That’s very okay, we said. You pay for the ambiance in these small bars.

Before I ordered, I asked the other guy what the cannabis beer tasted like. “It’s okay,” he said. “I like Budweiser.” I did not, but I knew the feeling. Budweiser wasn’t very good, but like Yebisu and Sapporo Black, it was different than what he was used to, and the exoticism of other countries’ cheap mass-market beer had its own appeal. Behind the counter, the bartender clicked a hand-crank flashlight to fetch beer from a tiny refrigerator. It only put out a tiny beam before it quit working. He’d click and shine, click and shine. The beam was so faint that he held the bulbs directly on whatever needed illuminating. It was comic. It was schtick. He seemed to enjoy it.

When our Japanese beers arrived, we clinked the cans against the other guy’s Bud. “Kanpai,” he said. Kanpai.

His name was Kaihei. He spoke excellent English. Without him, Rebekah and I would have sat in the dark struggling to exchange words with the bartender, who spoke as little English as we spoke Japanese, and would never have learned anything about this place.

Kaihei sipped his beer and tilted his head. “Why are you here? How did you know to come here?”

We explained: A friend insisted that we had to come here. She and her husband were walking around Osaka a few years ago and spotted the name Ganja Acid on the building, so they came back at night to check it out. They’d hung out in here with the owner, listening to Japanese psychedelic music. Kaihei nodded, and the bartender looked at him, squinting, wanting to know what we’d said. As he translated, the bartender leaned in excitedly, his brows raised, before asking follow-up questions: How did I know her? Where did she live?

They lived in California, I said. She was a writer, and he played in punk and pop bands and loved crating for rare pop, rock, and psychedelic records in Japan.

“Music?” the bartender said. He asked the bands’ names, then held his phone so close to his face that his nose seemed to touch the screen as he scanned Google results. The phone was the brightest light in there. When he found an article about one of the bands, he said, “Oh, California. California,” and scanned more details. The bar was so awkwardly cramped that I imagined he struggled to function outside, like the mole people of 1990s Manhattan who lived in old sewers under the streets and preferred the womb’s insularity to the noisy bright surface world.

The bartender’s name was Tetsujin. “His name means Iron Man,” said Kaihei. “Yes, like the song. And he is strong.” Kaihei smiled when asked if that was his real name. “Maybe not. I don’t know. It could be.” Iron Man owned Ganja Acid. “He is the Master. There was another master before. He is the second.” The bar had been open for over 20 years. Tetsujin pressed his little light against the back wall and scratched at something. I wondered what he did for work before this. Another bar? The music business? With his chill posture and low hat, it was hard to picture him taking orders from some straight-laced citizens, called katagi, in an office somewhere.

Kaihei was a regular. I asked: “Are you friends?”

“Yes,” he said. “Sort of. I come here before work a lot.”

“You’re just going to work now?” It wasn’t even 10 p.m. “You must work at a bar.”

He said sort of. “A host bar. I take photographs of the hosts.” He grinned. “You know?”

“Mizu shobai,” I said. “Yes.” In Japan, host clubs were places where people paid for companionship and, if they wanted later on, for sex. Host clubs sold male companionship to women, hostess sold female companionship to men. Japan didn’t have openly gay clubs for men yet.

As Tetsujin scrolled through his phone in search of songs to play, Kaihei explained how the host business worked, how, for the last three years, he got paid to catalog the same men over and over, in the same type of photos, as they posed in nice jeans and pressed shirts. He showed us images on his phone. The hosts’ faces were chiseled, their hair sculpted into messes, and their subtle makeup noticeable. They looked like members of K-pop bands: boyish and thin but almost asexual.

Like many sex businesses, this took place at night while the rest of us slept. “Cool that you get to drink before going to work,” I said. “We get in trouble for doing that.”

Kaihei laughed. The hosts drink even more, he said. “They can get very drunk. They have to control it, to be careful. But it’s hard.” Many photographers in America shoot weddings and corporate gigs to make a living and support their less-profitable artistic endeavors, but when I asked if he made art on the side, he shook his head no. “I take photographs for my job,” he said sternly. “It is my job.” He was tired of photographing men. “It is good work, but it is time to photograph girls. I am bored with boys. Want to photograph girls now.” With time, he could transition into that. “There is lots of work.”

Rebekah and I asked questions about host clubs, and he asked us questions about sex work in America: Do you have host clubs? Is prostitution legal? Rebekah explained how prostitution was only legal in one state in America: Nevada. “Near Las Vegas, of course.”

Kaihei nodded. “Ah, Las Vegas. I know it. I haven’t visited, but I know.” He was surprised that single men searched for dates at bars. “We go to strip clubs to meet girls.” Not to meet single customers, but to date the strippers themselves. That confused us. Our surprise confused him. “People don’t do this in America?”

No, Rebekah explained. “I think a lot of exotic dancers dislike their clients. It’s not really a dating scene. It’s about making money.”

Kaihei took a long deep drag of his smoke and said, “I see.” The idea of legal prostitution fascinated Rebekah and I as much as the idea of American courtship fascinated him. “How do men meet girls in America?” By accident, we said, in bars, online, and through friends. “And how did you meet?” Through a friend, we said and told the story of meeting at a mutual friend’s birthday party. “Japanese people don’t use online dating,” he explained. “It is not considered good. They are ashamed.” Yet from what we’d seen, no one seemed ashamed to use selfie sticks in public here. You’d think a technologically advanced, computer-savvy society like Japan, where an astonishing number of people walk while staring at their phones, would embrace online dating. But Japan had its own systems that worked on their island. Outside of it, it seemed idiosyncratic. Here, it made sense. Also confounding: gay sex clubs weren’t common, Kaishei said. “Very underground.” Prostitution was legal. Love hotels lined entire city blocks. Special vending machines sold used underwear. But men couldn’t openly date other men.

While we talked, Tetsujin sat and watched us, studying our lips and faces. He was trying to decipher the conversation, a little envious he couldn’t join. Rebekah and I felt the same at nearly every Japanese bar we went to, except this one. Sometimes Kaihei would fill him in in Japanese, and he’d nod, say a few things, and Kaihei would interpret for us. Often, Tetsujin would press his phone to his face and search for music to play. Sometimes he’d use Google translate to figure out a word we’d used, or to find a photo or map to show us: the Japanese artist Tarō Okamoto who built the huge Tower of the Sun statue on the outskirts of town that we should see; an old part of Osaka called Tobita-Shinchi, full of open prostitution they thought we’d find interesting.

Tetsujin scrolled through songs, drinking from a large brown and yellow milk carton, not even smoking. “He doesn’t take alcohol,” Kaihei said.

Tetsujin pressed his index fingers into both temples. “Natural high,” he said, tilting his head. “Natural high. Only cohee,” meaning coffee. He shook his nearly empty latte carton at us, rattling the remaining bits inside. Then he tipped back his head, swallowed the rest and tossed it across the room, where a stack of spent cartons filled the corner, floor to ceiling. They were all Yokankyo, his favorite brand.

Kaihei smiled. “Paranoid collector, see?”

Seeing was difficult. “It’s very dark,” I said.

“Usually darker,” said Tetsujin. Then he hit some switches and the place went black. Only one light remained. It glowed blue on the wall behind him. We laughed and sat in the dark for a moment, then he switched on a high red light. We sat in a red state for a while, staring at each other and taking in the vibe, then he flipped a switch and aimed a tiny yellow clip light at us which hung over the counter. “Spotlight,” he said with a laugh. With that, he returned us to the original dimness and the conversation continued.

At first, I thought Tetsujin’s abstinence was like those drug dealers who didn’t do drugs because they saw the damage it caused, but as Rebekah later pointed out, “take” might have meant that his body didn’t handle alcohol, so he refrained. About a third of Japanese people have bad physical reactions to alcohol thanks to a genetic inability to efficiently metabolize it. Maybe he was one of the third, but it was amusing to think that the owner of a bar named after two drugs consumed neither.

I explained that the name Ganja Acid sounded like a wild place filled with drug-fueled debauchery, but we were the only ones here, and its owner didn’t even drink alcohol. Kaihei said, “Westerners come trying to buy drugs. When they ask for them, he tells them no, no weed. They can get some at other bars. Not here. This bar is clean.” Kaihei ran a finger along the counter. “Very clean place. Just alcohol.”

Japan has a reputation as a hard-drinking country tolerant of public drunkenness. Sauced businessmen pass out in train stations. Coworkers haze each other at company booze parties, yet most mass-market Japanese beer contains five percent alcohol, with a few craft beers going as high as six or seven percent. Many mainstream brands make alcohol-free versions or “clear” beer; the country has the biggest selection of alcohol-free beer I’d ever seen because the market caters to those 30-something percent who can’t drink. Ganja Acid only served five beers, yet I drank mine and felt nothing. Maybe it was one of Japan’s ubiquitous free beers. Maybe it was the trippy environment. It was weird. In the dark, I couldn’t check the can.

Iron Man smiled. “Head trip.”

A bar owner who didn’t drink alcohol. A young guy who drank beer for breakfast at one bar before going to work at a sex bar. Beer that gave me no buzz. Nothing was what it seemed. It turns out that Ganja Acid wasn’t even one bar. It was two. Tetsujin explained: “Sign says Ganja, line, Acid,” “line” meaning slash. “Ganja, this. Acid next door.” The name I knew was a translation error. The official name was Ganja / Acid , because it was two bars. Ganja was a psychedelic bar. Acid was a music venue that hosted DJs and live bands — “gigs” as Kaihei called them. Two separate spaces, one owner, sharing a wall, joined by — or separated by / .

Acid was closed tonight. “No music right now,” Iron Man said.

This disappointed me.

First off, I’d become attached to the name. I liked the idea that someone felt their bar needed a name so powerful it required two illicit substances. That felt potent and comically subversive. Second, while planning our trip here, I’d started to fantasize what this place would be like, and I played with the idea that ganja and acid might symbolize rebellion in Japan’s conformist culture. Generally speaking, many Japanese people viewed drug use as a symptom of moral corruption, spiritual deficit, or personal weakness, a sickness rather than recreation or experimentation, as we view it in America. If Ganja Acid wasn’t about the drugs themselves, I figured, then maybe it was about symbols. Among Japan’s obedient rank-and-file, drugs might represent individuality, autonomy, or creativity, going against the notoriously strong grain. The people who did drugs were a certain type of people, so maybe some of them were the admirable kind who carved their own path, because in a country where concentric rings of social obligation influence behavior to the point that they can strangle individuality, many Western icons of rebellion are celebrated: James Dean, Buddy Holly, Jimmy Hendrix, Bob Marley, The Beatles. In this line of thinking, you don’t have to do drugs to rebel. You just have to associate with them, like how Japanese youth had famously embraced the marijuana leaf and Rastafarian yellow-green-red color scheme in advertisements, business logos, t-shirts, and album covers. In the absence of credible information, my mind filled with images of people drinking under the bar’s orange and yellow sign, the words “ganja acid” functioning as a glowing “fuck you” to those outside. Fuck your way of life. Fuck your opinions. Fuck your sense of obligation and judgment and thoughtless support of the status quo. Fuck what you think of us in here. We’re just drinking and listening to music. We’re not hurting anyone. This was a very American way of thinking. I was projecting and was way off base.

Tetsujin’s drugs weren’t symbols. They were advertisements, descriptions of each bars’ distinct themes and atmosphere. Acid meant loud, wild, crazy. Ganja meant chill. One side hosted live music. One offered a meditative space to drink. In the tiny three- or four-seat bars in Tokyo’s famous Golden Gai district, as well as Osaka neighborhoods like Namba, each had a theme. This one’s a Halloween-themed bar. That one’s an anime bar. That one’s punk. Ganja was a psychedelic bar, and its name announced the vibe. That was all.

Tetsujin didn’t play music himself. “Music in my head,” he said. The glass domes on the counter turned out to be speakers, not incense holders or vases. Not all of them worked. “He’s paranoid,“ Kaihei said. “He collects things: speakers, gig posters, cartons.” He played music through the functioning speakers. He kept the broken ones, Kaihei said, “just in case.”

The bar stayed open until 6 a.m., sometimes noon. “On New Year’s Eve it stayed open all night for three days,” said Kaihei. It depended on Tetsujin’s mood and the number of patrons. When I asked if other people tended bar during those three days, Kaihei said, “No, him! He does it all. I said he’s Iron man. Black Sabbath. Paranoid.” With all that sugary coffee, Tesujin could stay awake a long time.

After an hour, the door finally opened. One woman came in. She took the stool by the door and ordered a beer. Kaihei turned to see if he recognized her. They exchanged a few words. He turned back around. She drank her beer and left.

Rebekah decided to buy a Ganja 20th Anniversary t-shirt. She touched the hem of one hanging on the wall behind us. “I’ll take one of the yellow ones, please.”

“There is white,” Tetsujin said. “And there is black.” I squinted in the darkness, trying to see the shirt. It looked yellow to me. Maybe he had different ones in stock. I asked for black. He ducked behind a thin transparent curtain and pawed through a bunch of shirts in a cramped back area whose rear wall had the rough, gray patina of a cave. His flashlight cut a thin cone through the smoke. Every so often he’d crank it, then the light would dim and go out again. Eventually he emerged holding shirts. “Eto,” he said. “One small, one extra large.” I held the black XL to my chest. It hung like a dress. Sadly, too big, I said.

A member of the Japanese psychedelic band Yura Yura Teikoku, or The Wobbling Empire, designed the black shirt. He was a friend of Tetsujin’s. Yusuka Chiba, another musician, designed the white one, which fit Rebekah perfectly and made me jealous. I wanted a souvenir. I’d only have the experience.

Unfortunately, the smoke was killing us. Kaihei kept lighting cigarette after cigarette, filling the ashtray with butts, until his tiny pack lay crumbled beside us.

I leaned close to Rebekah. “You ready to hit the road?”

“Yes, let’s get out of here,” she whispered back. “I need to breathe.” The men stood up, and we all shook hands and exchanged goodbyes after Tetsujin photographed us in a silver explosion of light.

Coming out of the bar around 11:30, shuffling down the alley, drunks fumbled out of narrow doorways while others sipped from glasses at outside tables. Three guys in black jeans and jean jackets rolled guitar amps out of a tiny club and abandoned beer cars stood on curbs under the street lights. This city had so much life. I’d do anything to live here.

Under the street lights, we could see something else: The demo shirt we identified as yellow and that Tetsujin called white had actually been yellow. It was stained from the smoke. Rebekah held a strand of her hair to her nose. “Ugh,” she said, “I just washed my hair.”

•

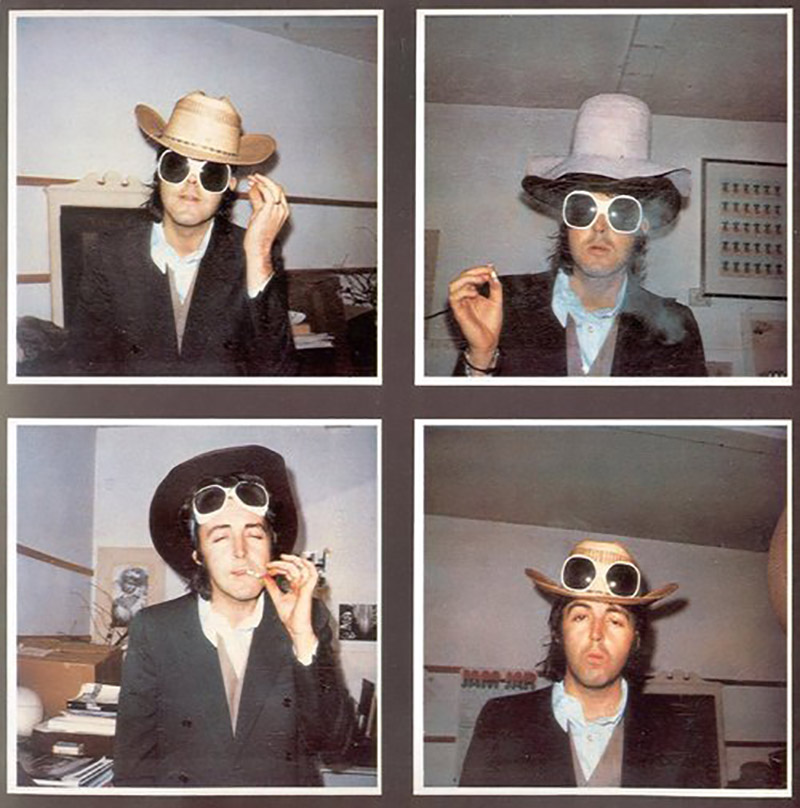

Comedian Bill Hicks spoke for many Americans when he said: “You see, I think drugs have done some good things for us. I really do. And if you don’t believe drugs have done good things for us, do me a favor. Go home tonight. Take all your albums, all your tapes and all your CDs and burn them. ‘Cause you know what, the musicians that made all that great music that’s enhanced your lives through the years were rrreal fucking high on drugs. The Beatles were so fucking high they let Ringo sing a few times.”

In 1980, Beatles bassist Paul McCartney famously got arrested at Tokyo’s Narita Airport for smuggling eight ounces of weed in his luggage. “Everyone had told us, ‘Don’t take drugs to Japan,’” McCartney later recalled about this doomed Wings tour. “I do not know what possessed me to stick this bloody great bag of grass in my suitcase. Thinking back on it, it almost makes me shudder.” I know what possessed him. He was a stoner, and stoners rarely travel without weed. Bob Dylan introduced McCartney to marijuana in 1964, when he passed The Beatles a joint in a New York hotel room. Paul remembers “giggling uncontrollably” that night. Soon after, he started smoking regularly, even getting stoned before the filming of The Beatles’ movie Help!, where he’d forget some of his lines. It kept on that way for a while. The Swedish government fined him £1,000 for possession in 1972. He got arrested for possession in Los Angeles in 1975, though got let off. No surprise he got popped in Japan: He was blasé. He brought weed everywhere. But Japan isn’t like everywhere. Once security found the bag hidden in his packed suit jacket, McCartney spent nine days in a ten-by-14 foot jail cell where he slept on a mattress on the floor. He cleaned his cell with a reed brush, got one cigarette break a day with other prisoners, and he got up early and went to sleep early — with books but no guitar. Facing seven years in prison, his band Wings had to cancel their eleven sold-out Japan concerts, which lost them upwards of a million dollars and pissed off the other players and roadies. Somehow, probably because of his celebrity and lawyers, the Japanese government decided to deport their famous criminal without a single charge, and he never played Japan again. Sir Paul got lucky. As Linda McCartney said in People, “It’s really very silly. People certainly are different out here.” That’s putting it lightly. The better way to think of it is that when you’re in someone else’s country, you have to be different there.

For a night spent at a bar named after two drugs, we got up at seven the next morning feeling refreshingly awake. No hangover, no tracers. Rebekah ran for an hour up to Osaka Station, and I drank tea and took a stroll. Kaihei had probably just gotten off work. What stayed with us was the smoke. Our clothes and skin reeked of it.

When Rebekah unfolded her Ganja t-shirt to take in its glory, she let out an amused groan. “Look.” A thick yellow line ran right across the center, under the word Ganja. Stored in the back room, it had absorbed nicotine.

“Maybe they should rename that place ‘Tobacco,’” I said. “It’s the strongest drug in there.”

Rebekah held up her shirt and studied the stain. “I could bleach it,” she said, “but it’s kind of great. Maybe it’s better to leave it as it is.” •

Images courtesy of Toomore, szeke, CaDs, saitonrock, inefekt69, Agent Smith, Paul Robinson, azaar94, Suzanne, Moyan_Brenn, Dakiny, Alexander Synaptic, tokyoform, Matt Henry photos, Thought & Sight, okadots, cloud2013, and jikatu via Flickr (Creative Commons).